Category: News

Marc Karlin’s Nicaragua – 36th Anniversary of the Sandinista Revolution – Amphitheatre Pedro Joaquin Chamorro – Cinemateca Nacional

BAMcinemaFest 2015 – Counting by Jem Cohen

“Counting” is Jem Cohen’s wandering tribute to the filmmaker Chris Marker, who died in 2012, and is structured as an essay-film told in 15 chapters of varying lengths. Cohen shot the footage during trips to Russia and Istanbul, and while walking around New York City, where he currently lives (many Brooklyn residents will see familiar landmarks, but Cohen’s camera-eye captures details that go unnoticed). Through his camera he constructs a personal travelogue that also acts as a map of the political climate of the last few years. But the energy of the film derives less from single images than the movement or flow of images. “Counting” reproduces the human experience of walking down the street, of wonder and concern and hope for the future.

via Whitechapel Gallery and Blouin Artinfo

Marc Karlin and Cinema Action 1968-1970

Promotional Material from Cinema Action’s Rocinante – found in the archive.

Last week in the BFI’s Essential Experiments slot, William Fowler presented the work of the filmmaking collective, Cinema Action. Two films were screen from the collective’s vast filmography – Squatters (1970), an attack on the Greater London Council regarding their lack of investment in housing . The film provided important – if controversial – information about the use of bailiffs in illegal eviction. And So That You Can Live (1981) which is widely recognised as one of Cinema Action’s finest works. The film follows the story of inspiring union convenor Shirley and the impact global economic changes have on her and her family’s life in rural South Wales. The landscape of the area, with all its complex history, is cross-cut with images of London, and original music from Robert Wyatt and Scritti Politti further reinforces the deeply searching, reflective tone. It was also broadcast on Channel 4’s opening night in November 1982.

Here is a history of Cinema Action via the BFI’s Screenonline

Cinema Action was among several left-wing film collectives formed in the late sixties. The group started in 1968 by exhibiting in factories a film about the French student riots of that year. These screenings attracted people interested in making film a part of political activism. With a handful of core members – Ann Guedes, Gustav (Schlacke) Lamche and Eduardo Guedes – the group pursued its collective methods of production and exhibition for nearly twenty-five years.

Cinema Action‘s work stands out from its contemporaries’ in its makers’ desire to co-operate closely with their working-class subjects. The early films campaigned in support of various protests close to Cinema Action‘s London base. Not a Penny on the Rent (1969), attacking proposed council rent increases, is an example of the group’s early style.

By the beginning of the seventies, Cinema Action began to receive grants from trades unions and the British Film Institute. This allowed it to produce, in particular, two longer films analysing key political and union actions of the time. People of Ireland! (1971) portrayed the establishment of Free Derry in Northern Ireland as a step towards a workers’ republic. UCS1 (1971) records the work-in at the Upper Clyde Shipyard; it is a unique document, as all other press and television were excluded.

Both these films typify Cinema Action‘s approach of letting those directly involved express themselves without commentary. They were designed to provide an analysis of struggles, which could encourage future action by other unions or political groups.

The establishment of Channel Four provided an important source of funding and a new outlet for Cinema Action. Films such as So That You Can Live (1981) and Rocking the Boat (1983) were consciously made for a wider national audience. In 1986, Cinema Action made its first fiction feature, Rocinante, starring John Hurt.

Marc Karlin joined Cinema Action in 1969. He had just returned to London after being caught up in the events of May ’68 in Paris while filming a US deserter. It was there where Karlin met Chris Marker, who was editing Cine-Tracts (1968) with Jean-Luc Godard at the time. Marker had just formed his film group SLON and had since released Far from Vietnam (1967), a collective cinematic protest with offerings from Jean-Luc Godard, Alain Resnais and Agnes Varda, inspired by the film-making practices of the Soviet film-maker, Alexander Medvedkin. The idea of taking this model of collective filmmaking back to the UK appealed greatly to Karlin, and was shared by many of his contemporaries. He details this enthusiasm in an interview with Sheila Rowbotham from 1998…

…when Marker started SLON, ideas about agitprop films were going around. Cinema Action had already started in England by 1969 when I joined. There was a relationship to the Russians: Vertov, the man with a movie camera, Medvedkin and his Russian agitprop train; the idea of celebrating life and revolution in film, and communicating that. Medvedkin had done that by train. SLON and Cinema Action both did it by car. Getting a projector, putting films in the boot, and off you went and showed films – which is what we did…

…when I joined there was no question of making documentaries for television. We showed our films at left meetings, where we would set up a screen, do leaflets and so on. It is often hilarious. I remember showing a film on housing in a big hall in the Bull Ring area of Birmingham. It started with machine gun noises, and Horace Cutler, the hated Tory head of the Greater London Council, being mowed down. The whole place just stopped and looked, but, of course, as soon as you got talking heads, people arguing or living their ordinary lives, doing their washing or whatever, we lost the audience. I learnt something through seeing that.

Evidently, Karlin was frustrated about the political and aesthetic approach of Cinema Action. In fact, salvaged in the archive is two thirds of a letter written by Karlin to Humphry Trevelyan that goes into some detail over the reasons for why Karlin intended to leave Cinema Action. For now, here is Karlin giving a somewhat exaggerated reason for leaving in the interview with Rowbotham…

…Schlacke (Cinema Action co-founder) had a thing about the materialist dialectic of film. Somehow or other – and I can’t tell you how are why – this meant in every eight frames that you had to have a cut. Schlaker justified this was some theoretical construct, but it made his films totally invisible. After a time I just got fed up. James Scott, Humphry Trevelyan and I started The Berwick Street Film Collective and later went on to join Lusia Films.

The Berwick Street Film Collective’s Nightcleaners (1975)

Find out more about the figures involved in Cinema Action and other British film collectives.

And…

Looking at Class. Film, Television and the Working Class in Britain, S, Rowbotham & H, Beynon, (Rivers Oram Press:2001)

Visual Pleasure at 40: Laura Mulvey in discussion (Extract) | BFI

Academic-filmmaker Laura Mulvey discusses her groundbreaking essay ‘Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema’, published 40 years ago in 1975. Filmmakers Joanna Hogg and Isaac Julien join academics John David Rhodes, Tamar Garb, Mandy Merck and Emma Wilson to celebrate this “feminist manifesto”, a product of the politics of its time but one which remains an inspiration today.

The discussion was part of the BFI’s Cinema Reborn. Radical Film from the 70s season in April 2015.

On reaction from the conference please read Sophie Monks Kaufman’s The Timeless Pleasure of Laura Mulvey in Little White Lies, where she asks – can Laura Mulvey’s seminal feminist essay tell us anything new about gender politics in cinema?

And Benedict Morrison’s Galvanising the Humanities in The Oxonian Review.

Via BFI

Cinema Action – Steve Sprung – He Wanted to Make Movies the Way Everybody Else Does!

Tonight at the BFI, Southbank sees a celebration of the work of the film collective, Cinema Action. After a screening of Squatters (1970) and So That You Can Live (1981), Ann Guedes and Steve Sprung, Cinema Action members, will be present for a Q&A.

Steve Sprung was a key collaborator with Marc Karlin on five films and later contributed to the book Marc Karlin – Look Again.

Here is Steve’s article on Karlin from the summer of 1999. It featured in an issue of Vertigo magazine dedicated to Karlin, who died in the January of that year.

It’s hard to imagine it, the idea of Marc turning in his grave, but surely he must have. May Day… Saturday the first, not Bank Holiday Monday.

Nothing to do with his beloved Arsenal, but with that other, mostly negative, mover of his being, television. In a programme hosted by Jon Snow the British people were allegedly invited to make a late but vitriolic judgement on Margaret Thatcher’s seventeen years in government.

I imagined the rage it would have elicited from Marc – not against the obvious target, Thatcher and her die-hard crew – but against all those claiming it was Maggie who done it, that this she-devil incarnate must now take all the blame. At a time when cleansing, by all manner of powers over other powers, dominates our television screens, this was an equally crude wiping clean. Television’s refusal to engage with the complex process of those years – years which constitute a substantial chunk of our adult lives as well as moulding future generations – would have had him livid.

It was this Thatcher period which formed the context for my work with and for Marc. My background had been in a more agitational cinema, but I had been struggling for years, labouring away in the basement under Lusia Films, with a film about a failed strike under the previous Labour government, and its role in laying the ground for the Thatcherism that was to come. How to talk about events which had been mischaracterised both by the dominant media industry and by the working classes’ own trade union and political organisations? How to reveal this massive content, tell this necessary story, and find an adequate form in which to do it?

This film, The Year of the Beaver, finally emerged in the early eighties. It manages to create multiple layers of meaning, drawing connections between the myriad things it had been necessary to take on board. When he saw it, Marc hugged me. This, I felt, was our first real meeting. On looking again at Marc’s early films, I came to realise they had always been about looking beneath the surface to reveal connections. In a sense they are films which try to open up for the viewer the process we went through as filmmakers, inviting them, as far as was possible, to share the journey we had made. Thus they were films which interrogated their audiences as much as they interrogated their subject-matter, just as we had interrogated ourselves as part of their making.

I worked on five films with Marc. I was one of many with whom he talked at great length about the ideas underpinning each new project. We would try out sequences with video-cameras, and these I would cut and re-cut, often summoned to Lusia by a Saturday morning ’phone call.

I chose not to attend the actual shoots (on 16mm) so that I could come to the rushes with as fresh an eye as possible. It was as if the material had been encircled, caught by the camera. Now the ideas, and the film which would bear them, had to be re-discovered, and brought to life on the editing table.

The Outrage, 1995

Marc, insecure as he was, as we all are when laying ourselves on the line and taking risks to say more than we readily know how to say, was incredibly secure in terms of entrusting me with the material. When viewing my cuts, he had the sharpest eye for detail, and its relationship to the whole, but he gave me unhindered space in which to work. He never demanded that this or that shot must be used, and was in this sense able to subsume his ego to the film.

Why?

Because the films were about something bigger than Marc or any of us who worked on them, and we were simply engrossed in trying to understand how to bring the ideas to life.

Paradoxically perhaps, the first film I edited with Marc was the last of his more conventionally “political” and “documentary” works.

Between Times was a journey through the countervailing political ideas of the “in between times” he felt we were in, and through the sort of questions Marc felt this period posed for anyone still concerned with bringing about revolutionary change. I’ll always remember the end of the film: the two protagonists, who’d been conducting an argument by presenting various documentary stories, were revealed to be one single, contradiction-filled person. But this was a person who held on to a simple truth: when we had none of the technology to construct a new world we had the capacity to dream it; now that we had the technology, we seemed to have lost the capacity to dream the dream.

Between Times was a turning point in his and our filmmaking. Marc moved towards the politics of culture and away from films whose legitimacy derived from concrete documentary material based on ongoing political action. He went for a new type of direct cinema, looking at how the world is culturally constructed and by whom, and exploring the blockages preventing perceptions of the world which are different from those of the more dominant vision.

The Outrage, 1995

This required a different use of the material basic to documentary filmmaking, an approach which freed itself from following the sequence of particular events or political actions. It was an approach I had begun to explore in a film I had recently co-directed, Men’s Madness, and something which Marc’s practice, and his work with people such as Chris Marker, had enabled him to appreciate. He saw it as a step forward in opening up the political space of cinema, and he continued to develop it further in his films, drawing increasingly on fictional and scripted elements.

In The Outrage, a man goes in search of a painting, or, rather in search of the art in himself. This film shows another aspect of Marc’s work: the supposed subject of the film – in this case a portrait of the artist Cy Twombly – is turned upside down and viewed from an unexpected angle. Thus we are able to look at the subject afresh, to look at art and painting from the point of view of the viewer. We go through precisely the process of re-discovery Marc had gone through to be able to create the film. This journey we, his collaborators, had also shared, leading us to engage with that essential need which emerges as art. Not the art of the market place, but the art that most of us leave behind somewhere in childhood, in the process of being socialised into the so-called real world. The art which still yearns within us.

The Outrage contained an important sequence which talked about the role of advertising (and this includes MTV) in our visual culture. This is the one place where it is permitted for images to be freely given over to the imagination. But here imagination has become no more than a commodity, and the images bear the emptiness of this prostitution. In contrast, the richness of The Outrage’s visual imagery and the imaginativeness of its narrative form are inseparable from an equally rich and meaningful content. The film’s imagery does not flow over and mesmerise the viewer; it asks for a more complete involvement.

Marc’s next film, The Serpent, about the demonising of Rupert Murdoch, continued this rich texturing of image, sound and meanings. I’m sure Marc had experienced visions of Murdoch horned and spitting fire, but he wanted to interrogate that whole process of “demonising” which we all revel in. He wanted, crucially, to look at what it really avoids, to address the difficult political questions it allows us to duck; how to fight against a culture which apparently offers more of everything, more channels, more choices, more democracy, more freedom? and how to ask another simple, yet largely unasked, question – where are all these choices leading? Freedom to do what?

It was during the making of The Serpent that Marc introduced Milton to me and to his films, in the epic form of Paradise Lost. This poem had obsessed him for some considerable time. It speaks of the devil not from a moral perch, nor of him as a foreigner, but as being resident somewhere in all of us. It was more than the text, however, that was rhyming with us. Just as Milton became isolated in his lifetime through his constant search for illumination, labouring to understand why the revolution of his time had failed, so we too were destined to a similar isolation. We had made ourselves outsiders by virtue of our way of working, by the endeavour of Marc’s kind of filmmaking. Perhaps this was the only place we could be. We required an audience who wished to make a journey similar to ours, whereas we live in a society in apparent need of constant triviality, one afraid to take itself too seriously for fear of what it might uncover, and desirous of seemingly “entertaining itself to death”. Perhaps this is the message of Murdoch’s easy victory.

The Outrage, 1995

This experience of being outside, witnessing a culture whose memory is in a dangerous state of decay, provided the impetus for The Haircut (a short about the cultural conformity of New Labour) and for Marc’s last work in progress on Milton: A Man who Read Paradise Lost Once Too Often.

Marc was preparing to keep up the fight. Coming from a different space, I had my reservations. The references that resonated for him were different from mine. I also knew he was engaged in a holding operation, perhaps one which few would be able to understand.

The film was not to be.

I can remember a sense amongst many of us present in the pub after Marc’s funeral of this being the end of an era. Would there be space in future for his kind of work? Where would it find its funding?

It seems to me there is an equally important question before us: will we be able, as time goes by, even to conceive of such work? It requires a skill that can only be developed through practice, and a great deal of time – gestation time and, especially, post-production time.

Marc’s are films about a process, and thus they have an organic life to them. They were not made with an eye to filling a television slot, but were designed to take the time they needed to take to communicate the exploration they had undertaken. This is why their significance lingers on beyond the momentary blip they represented in the continuous present that is television, and why they will outlive their own time. They are representations of the complex processes by means of which we come to understand who we are, where we are and what we are.

Steve Sprung is a film director and editor.

Vertigo Volume 1 | Issue 9 | Summer 1999

In Conversation – Ken Loach with Cillian Murphy

BFI Fellow Ken Loach joins actor Cillian Murphy In Conversation, having worked together on The Wind That Shakes The Barley, bringing them both a BIFA award for Best Actor and Best Director as well as the Palme d’Or for the film. Ken Loach was awarded the BFI Fellowship in 1996 and became a BAFTA Fellow in 2006, as well as receiving countless international awards for best director and best film for his prolific film and television output. Known for his social realist approach and engagement with socialist themes, including homelessness in Cathy Come Home, the Iraq occupation in Route Irish and resistance in the Spanish Civil War in Land and Freedom, Loach founded independent production company Sixteen Films which continues with strong critical success.

The conversation focuses on Loach’s dedicatation to documenting social and political injustice, the importance of artistic collaboration, the often-overlooked humour in Loach’s films, and the impact working with Loach had on his own approach to acting.

Also highlighted is the controversy surrounding Loach’s trade union documentary A Question of Leadership, intended for national ITV broadcast. It was criticised by the Independent Broadcasting Authority for its explicitly anti-government stance. It was eventually screened a year later, exclusively in the Midlands (tx. 13/8/1981).

Believing that the then-new Channel 4 would be more amenable to politicised documentaries, Loach proposed the four-part Questions of Leadership (1983), a wider-ranging study of the trade union movement – but on viewing the completed programmes’ strong criticism of leading trade unionists, an anxious Channel 4 shortened the series to two parts and proposed screening a ‘balancing’ documentary by a different filmmaker, before scrapping the broadcast altogether.

Documents detailing Questions of Leadership can be read here at the BFI, Special Collections. For more on the Ken Loach documentation collection at the BFI, read Wendy Russell’s report from 2011.

via BFI Screenonline

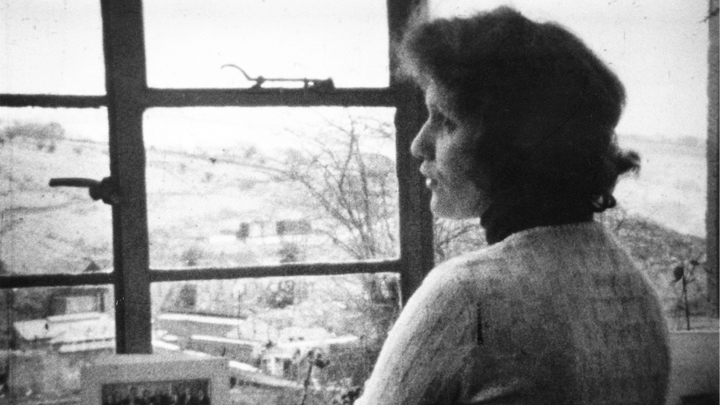

550 boxes – Chris Marker’s Collection – Cinémathèque française

The Cinémathèque française have just released an update on their recent acquisition of Chris Marker’s archive. Thanks to ChrisMarker.org for translation.

In the Spring of 2013, the Cinémathèque française took possession to its archives 550 large moving boxes containing the archives of Chris Marker, deceased during the summer of the preceding year. Under the conduct of a scientific committee of individuals close to the filmmaker and familiar with his work, the inventory of the estate began rapidly. The total duration of the operation was estimated at around three years. So where are we, two years later?

The 550 boxes that make up the estate are divided as follows:

5 boxes of posters; 6 boxes of LP records and musical documents; 15 boxes of photographs; 55 boxes of objects, miniatures…; 66 boxes of audiovisual material (Beta, master…); 98 boxes of archives (press documentation, files & folders); 112 boxes of VHS and DVD edits and personal recordings; 137 boxes of periodicals and books.

At this point in time, the boxes of photographs have been thoroughly inventoried, although not all photographs have been identified. Similarly, the inventory of ‘apparatuses/apparatii’ [appareils] is complete. The library of Chris Marker, rich with some 137 boxes, has been made the object of a deeper study and is approaching completion. An actively used library, as opposed to a collector’s library, it presents a singularity in so far as each work is stuffed with diverse documents: letters, press clipings, etc. Each volume therefore has been the object of a precise description of the elements that it contains. To get an idea of this library, the inventory would be certainly instructive, but evidently insufficient. A virtual library project is therefore being considered.

The inventory continues currently with the objects, posters, audiovisual materials and paper archives. This work should be completed by Fall 2015. The inventory of hard drives, on which Marker worked during the course of the last 20 years of his life, has also begun. These discs contain several million files. To bring to fruition the description of their contents will be a long-term work [‘de longue haleine’, literally ‘of long breath’]. Similarly, initial work on the state of more than a thousand digital diskettes [floppies/zip/flash drives presumably] has begun with the help of a digital conservation specialist [digital archivist]. A work of securing and restoring, an indispensible prior step to taking an inventory, will be conducted in the coming months.

During the course of the Fall, the VHS, DVD, CD and vinyl LPs will be inventoried, permitting thereby, with the horizon of Summer 2016, to have analyzed the sum total of the boxes of the estate and to have arrived at an initial, global view of its coherence and richness. Work on cataloging can then begin, with the objective remaining to place the estate at the disposition of researchers starting in 2018, while presenting it as well in the form of a grand exhibition at the Cinémathèque française. The scientific committee is already working toward this goal.

via chrismarker.org

The Serpent (1997)

Broadcast 21 August 1997, Channel 4 (FILMS OF FIRE) (40 mins)

Filtered through Milton’s Paradise Lost, Michael Deakin, a London architect, decides to rid Britain of Rupert Murdoch and all his works. But ‘The Voice of Reason’ has other plans.

Director – MARC KARLIN

Production Company – LUSIA FILMS

Executive Producer – MAGGIE KOSOWICZ

Producer – MARC KARLIN

Production Assistant – KATIE BOWDEN

Lighting Cameraman – JONATHAN BLOOM

Assistant Camera – MICK DUFFIELD

Sound – JOHN ANDERTON

Gaffer – MATTHEW MOFFATT

Editor – STEVE SPRUNG

Assistant Editor – MARCEL LACUNEO

Dubbing Mixer – CLIFF JONES

On-line Editor – DIMITRIOS EVANGELOU

Production Designer – JUDITH STANLEY-SMITH

Art Assistant – LOUISE SHAW

Costume Designer – ASTRID SCHULZ

Make-up – NORA NONA

Animation – ALEX QUERO – 41 Films

Michael Deakin – NICHOLAS FARRELL

Lenin – RUSS KLINGER

Murdoch – RON BONE

Voice of Reason – FIONA SHAW

Storyteller – SCOTT HANDY

Twin (young) – BOBBI WILLIAMS

Twin (young) – JOSEPH WILLIAMS

Between Times (1993)

Broadcast 4 November 1993 Channel 4 (CRITICAL EYE) (50 mins)

An essay on the future of the British Left, through the different perspectives of A and Z. In their wide-ranging search for alternatives the question is posed – is it still possible, even desirable, to draw a political map?

Director – MARC KARLIN

Script – MARC KARLIN & JOHN MEPHAM

Lighting Cameraman – JONATHAN BLOOM

Sound Recordist – JOHN ANDERTON

Production Manager – CATHERINE OSTLER

Designer – MIRANDA MELVILLE

Editor – STEVE SPRUNG

Online Editor – TOBY RISK

Dubbing Mixer – PETER HODGES

Storyteller – LAHOR RUDDY

A Dream From The Bath (1985)

Commissioned by Large Door and broadcast on Visions, Channel 4’s film programme, is a response to the Film Act of 1985, questioning the role of cinema in structuring our sense of belonging, and the need for a pluralist cinema free of national stereotypes.

Director – MARC KARLIN

Camera – JONATHAN BLOOM

Assistant Camera – JEFF BAGGOTT

Sound – MELANIE CHAIT

Editor – ESTHER RONAY

Assistant Editor – NINA DANINO

Video Editor – KELVIN DUCKETT

Mixer – DAVID OLD

Actors

Women in car – CAROLINE HUTCHINSON

Woman outside cinema – JULIA WATSON

Man outside cinema – PETER HARDING

Thanks to John Cross, Carl Ross, The Rising Sun, St Mawes, Cornwall

Produced by Large Door