Category: Video

Look Again #3 – Sally Potter

Sally Potter writes a beautiful, heartfelt foreword in Marc Karlin – Look Again, describing Marc Karlin as a cinematic pioneer, thinker and activist. She also goes on to recall her first meeting with Karlin, after a screening of Nightcleaners, and how he kindly shared the Berwick Film Street Collective’s facilities while she was making her film, Thriller in 1979.

Here is an interview between Sally Potter and Wendy Toye, broadcast on Channel 4 on 9th May 1984. It was commissioned for the film programme, Visions (1983-1986). John Ellis, who co-produced the programme via his company Large Door, has very recently uploaded a collection of complete episodes from the series. ‘So there is now a Large Door channel for our moribund independent production company, with a selection from the hundred or so programmes we produced’.

Two women directors of different generations – both trained as dancers – meet for the first time. Sally Potter’s first feature ‘Gold Diggers’ had just been released. Wendy Toye’s career began in theatre and she directed her first short ‘The Stranger left No Card’ in 1952. She worked for Korda and Rank, making both comedies and uncanny tales. Directed by Gina Newson for Channel 4’s Visions series, 1984.

Large Door was set up in 1982 to produce Visions, a magazine series for the new Channel 4. Initially there were three producers, Simon Hartog and Keith Griffiths and John Ellis. Visions continued until 1986, producing 36 programmes in a variety of formats. Hartog and Ellis continued producing through the company, broadening out from cinema programmes to cover many aspects of popular culture from food to television.

Visions was a constantly innovative series, and John Ellis’ article in Screen Nov-Dec 1983 about the first series gives a flavour of its range:

Especially during the earlier months of production, we vacillated between two distinct conceptions of the programme: one, the more conventional, to use TV to look at cinema; the other, more avant-gardist, to treat the programmes as the irruption of cinema into TV. […]

We found that virtually all of our programme items could be categorised into four headings:

1) The Report, a journalistic piece reflecting a particular recent event: a film festival like Nantes or Cannes, the trade convention of the Cannon Classics group.

2) The Survey of a particular context of film-making, like the reports from Shanghai and Hong Kong, and the critical profile of Bombay popular cinema.

3) The Auteur Profile, like the interviews with Michael Snow and Paul Schrader, Chris Petit’s hommage to Wim Wenders, or Ian Christie’s interviews with various people about their impressions of Godard’s work.

4) The Review, usually of a single film, sometimes by a literary intellectual, ranging from Farrukh Dhondy on Gandhi to Angela Carter on The Draughtsman’s Contract. About half the reviews were by established film writers, like Colin McArthur on Local Hero or Jane Clarke on A Question of Silence.

The third series of Visions, a monthly magazine from October 1984 added further elements. Clips was a review of the month’s releases made by a filmmaker or journalist (eg. Peter Wollen, Neil Jordan, Sally Potter) consisting entirely of a montage of extracts with voice-over. We introduced the idea of the filmmaker’s essay, borrowed from the French series Cinema, Cinemas, commissioning Chantal Akerman and Marc Karlin to do what they wanted within a limited budget and length. The plan to commission Jean-Luc Godard fell in the face of his insistence on 100% cash in advance with no agreed delivery date. And then there was no further commission.

Further Reading and Viewing

http://cstonline.tv/resurrected-visions-on-youtube-the-large-door-channel

https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCkw6_1SR89FKzlV50e0aWAQ

https://vimeo.com/user12847153

http://www.screenonline.org.uk/people/id/490062/

Charlotte Crofts (2003) Anagrams of Desire: Angela Carter’s Writings for Radio, Film and Television(London: Chatto & Windus), pp. 168–193

John Ellis Channel 4: Working Notes, Screen, November-December 1983 pp.37-51

John Ellis Censorship at the Edges of TV – Visions, Screen, March-April 1986 pp.70-74

John Ellis Broadcasting and the State: Britain and the Experience of Channel 4, Screen, May-August 1986 pp.6-23

John Ellis Visions: a Channel 4 Experiment 1982-5 in Experimental British Television, ed Laura Mulvey, Jamie Sexton, University of Manchester Press 2007 pp.136-145

John Ellis What Did Channel 4 Do For Us? Reassessing the Early Years in Screen vol.49 n.3 2008 pp.331-342

Look Again #2 – Hugh Stewart

Imperial War Museum – Hugh Stewart

In the lead-up to the release of Marc Karlin-Look Again here are a collection of portraits focusing on the people Karlin documented in his films.

Hugh Stewart was a film editor and latterly a film producer. After graduation from college he joined Gaumont-British Picture Corporation on an apprenticeship scheme working as an assembly cutter. After impressing Alfred Hitchcock, he was asked to supervise the edit on The Man Who Knew Too Much (1934). Speaking in 1999, Stewart recalls the the production,

When he (Hitchcock) came on stage for the first day of shooting, he put the script down and said, “Right, another one in the bag.” Not that he had any disrespect for the making of the film, but as far as he was concerned, he knew the film so well, it was already in his mind. The Albert Hall sequence was the major example of it.

In the story the mother, Edna Best, went to a concert at the Albert Hall. As she sat there she realised that an assassin was going to kill an ambassador sitting in the Royal Box. The assassin had also stolen her child, so she was there with a double purpose. The words of the chorale being performed included the phrase “Save the Child,” which was an ingenious underlining of the second motif which was in her mind, though not in the visible action. Hitchcock made a variety of shots, and the author had the task of piecing them together, using the music as a frame-work.

And here Stewart recalls his editing work on a Michael Powell production. A similar occasion had arisen during the making of “A Spy in Black,” a good film made by Michael Powell in 1938. A German “U” Boat, with Conrad Veidt as Captain, was making its way through a minefield outside the Orkneys. The quality of suspense was very necessary, so a few chart inserts were shot, some underwater submarine shots were found, and a delightful couple of days were spent working up a sequence.

When war broke out in 1939, he immediately joined the Royal Artillery. He was commissioned in the AFPU (Army Film and Photographic Unit) in December 1940 and led No 2 AFPU in covering the Allied landings in Tunisia in November 1942. A year later he co-directed Tunisian Victory (1943) with John Huston and Frank Capra.

Later, as head of No 5 AFPU, Stewart and his combat cameramen covered the British D-Day landings, the Caen breakout, the Rhine Crossing and the Battle of the Ardennes — as well as the liberation of Bergen-Belsen.

When Belsen was voluntarily turned over to the Allied 21st Army Group on April 15 1945, Stewart was head of No 5 Army Film and Photographic Unit (AFPU). As such he was under strict War Office orders to remain with the British Army as it advanced further into Germany. But realising the significance of the scenes at the camp, he decided to go over the heads of his superiors and make a direct appeal to Eisenhower, arguing that it was vital to prepare a cinematic and photographic record.

Eisenhower overrode the War Office, and in the days after the liberation Stewart and his team undertook the harrowing job of filming the camp. Towards the end of his life Stewart said that not a single day had gone by without him remembering by sound, sight and smell of what he witnessed during those few days. Later he was consulted by the research team for Steven Spielberg’s Schindler’s List (1993).

Before contributing to Schindler’s List production, Hugh Stewart appeared in Marc Karlin’s For Memory (1982) co-produced by the BBC and BFI. It was a film about the fragility of memory. Ironically, this film about memory was forgotten by BBC, only being broadcast at a sleepy Easter slot in 1986. Karlin had been extremely unnerved by the miniseries Holocaust (1978), Hollywood’s serialisation of the genocide starring Meryl Streep and James Woods, portraying the (fictional) Weiss family of German Jews. Karlin found the series an offensive account of the holocaust, writing in his notebook: how could a documentary photograph die so soon and be taken over by a fiction?

This line of thought is expanded upon in an extract from For Memory’s commentary,

For some, ill-prepared to deal with the transformation of a sacred memory into a fictional melodrama, the images of Holocaust were a desecration, the betrayal of what had been considered an untouchable testimony to those events. But for others, these new reminders were the best that could be done to save these memories from the threat of oblivion. In the space of one generation, photographs and documents were judged to be no longer able to carry the weight of the events they once portrayed.

Marc Karlin approached Hugh Stewart, together with his AFPU camera Joe Perry, in 1980 and asked them to recount exactly what they could remember about that day in 1945.

For Memory begins, like other Karlin films, a fade in on a subject, without caption or a guiding voice-over.

Further Reading

http://the.hitchcock.zone/wiki/Hugh_Stewart

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hugh_Stewart_(film_editor)

http://www.altfg.com/blog/movie/hugh-stewart-death-film-editor-hitchcock/

Look Again #1 – Marsha Marshall

In the lead-up to the release of Marc Karlin-Look Again here are a collection of portraits focusing on the people Karlin documented in his films. Up first is Marsha Marshall, secretary of the Women Against Pit Closures (Barnsley Group) during the 1984-85 Miners’ Strike.

Marsha Marshall circa 1986 ©The Marc Karlin Archive

Marsha Marshall, who died in April 2009, lived with her miner husband, Stuart ‘Spud’ Marshall, in Wombwell, near Barnsley at the time of the 1984/84 Miners Strike. Spud was one of the first to be arrested during the dispute on a picket line in Nottinghamshire. This event politicised Marsha, and soon with others she founded the Women’s Against Pit Closures. Having never been abroad before, her duties as secretary of the WAPC, took her to France, Italy, Bulgaria, and the USSR – and in Rome she spoke at a rally to over 4,000 Italian trade unionists.

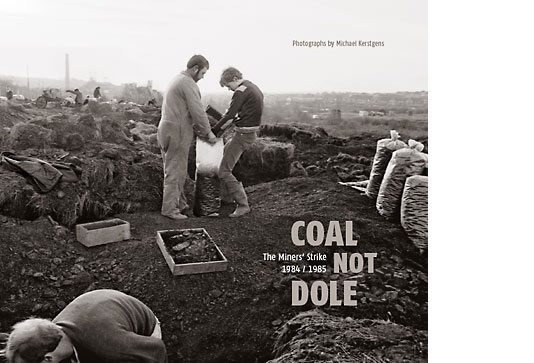

Marsha is featured in Michael Kerstgens’ photographic collection, Coal Not Dole, The Miner’s Strike 1984/85 published by Peperoni Books. In 1984, Michael Kerstgens was a young German photography student who decided to travel to Britain and document the dispute. People were wary of him, as an outsider, and so he was limited to photographing events on the periphery.

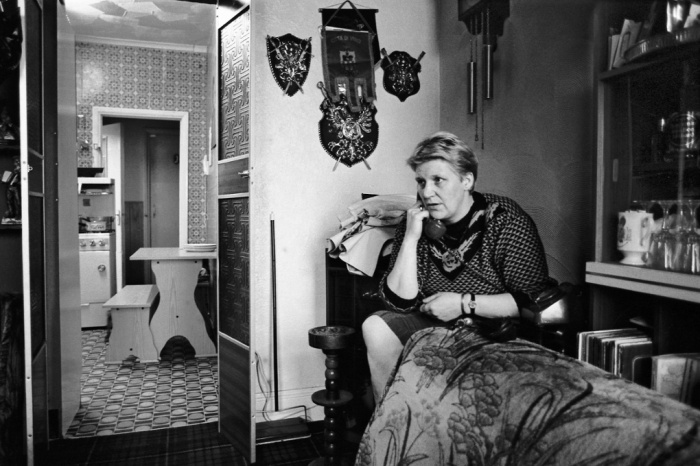

However, things changed when he met the activist Stuart “Spud” Marshall. Spud trusted him immediately and opened the door for Kerstgens to photograph not only the heat of the action but also more intimate moments beyond the picketing, violent clashes with the police, and public discussions on the political stage. Kerstgens photographed soup kitchens, meetings behind closed doors, and the wives of striking miners, including Marsha.

Marsha Marshall supports picketing miners with a donation of cigarettes. © Michael Kerstgens

Marsha Marshall on the telephone to Vanessa Redgrave, Wombwell, 1985, © Michael Kerstgens

Around 1986, Karlin interviewed Marsha Marshall for his film ‘Utopias’ – a film about socialism in Britain, broadcast on Channel 4 in 1989. Marsha would be one of the socialist voices in his film. Karlin, here, recalls his creative intentions,

I was filming Utopias in 1986, around the time Margaret Thatcher said she aimed to destroy socialism once and for all. I was determined to say otherwise, obviously. I wanted to do portraits of different socialism, take ideas about it and so on, but to put them all on one boat. Utopias was like a banquet table. I liked the idea of having somewhere all these people could be together, where David Widgery, Sheila Rowbotham and Jack Jones, Sivanandan, Bob Rowthorn, and the miner’s wife, Marsha Marshall, were all going to be there. All these visions of socialism were great. I am totally naïve, but I shall remain to the end, so I just wanted them all at the table. Can you imagine? No: But the film did.

Marc Karlin and Marsha Marshall, circa 1986, ©The Marc Karlin Archive

This is an edited extract of Marsha’s chapter from ‘Utopias’. In this section she recalls the miners’ strike and speaks about her fears for the future of her community.

‘Spud’ Marshall at home in Kendray Barnsley, September 2012 © Michael Kerstgens

Further Reading –

Coal Not Dole, The Miners’ Strike 1984/1985, by Michael Kerstgens, is published by Peperoni Books

http://peperoni-books.de/coal_not_dole00.html

http://www.southyorkshiretimes.co.uk/news/local/strike-hero-marsha-dies-at-64-1-615649

Looking at Class. Film, Television and the Working Class in Britain, S, Rowbotham & H, Beynon, (Rivers Oram Press: 2001)

Introduction by Federico Rossin. A Time for Invention. Part One

“We want to make films that unnerve, that shake assumptions, that threaten, that do not soft-sell”

Robert Kramer, ‘Newsreel’ Film Quarterly, Vol. 22, No. 2 (Winter, 1968-69), p.46, University of California Press

The late ’60s and ’70s saw the development of documentary film collectives in the UK that addressed the burning political issues of their day. They developed radical forms of independent film production and distribution prior to digital or the web and produced a large body of work, from short agitational cinetracts to sophisticated essayistic features.

The symposium seeks to re-ignite the work of this radical wave, to ask how they engaged with politics and film and how this might inform politically engaged filmmaking today. It will feature films, and filmmakers, from the ’70s generation alongside radicals of today. Here is the keynote address by Federico Rossin (Critic and Curator).

Introduction by Federico Rossin. A Time for Invention. Part Two

The symposium is supported by: Sheffield Hallam University, Sheffield Institute of Arts, Art and Design Research Centre, Sheffield Doc/Fest

Producers: Virginia Heath, Esther Johnson, Steve Sprung

Sans Soleil – Chris Marker (30th Anniversary Trailer)

Wim Wenders’ documentary Room 666 (1982) – “Is cinema a language about to get lost, an art about to die?”

During the Cannes Film Festival in 1982, Wim Wenders set-up a static camera in a room at the Hotel Martinez. He then invited a selection of directors to answer a series of questions on the future of cinema: “Is cinema a language about to get lost, an art about to die?”

The directors, in order of appearance were:

Jean-Luc Godard

Paul Morrissey

Mike De Leon

Monte Hellman

Romain Goupil

Susan Seidelman

Noël Simsolo

Rainer Werner Fassbinder

Werner Herzog

Robert Kramer

Ana Carolina

Maroun Bagdadi

Steven Spielberg

Michelangelo Antonioni

Wim Wenders

Yilmaz Güney

Each director was alloted 11 minutes (one 16mm reel of film) to answer the questions, which were then edited together by Wenders and released as Room 666 in 1982. Interestingly each director is positioned in front of a television, which is left on throughout the interview. It’s a simple and effective film, and the most interesting contributors are the usual suspects. Godard goes on about text and is dismissive of TV, then turns tables by asking Wenders questions; Fassbinder is distracted (he died within months) and quickly discusses “sensation oriented cinema” and independent film-making; Herzog is the only one who turns the TV off (he also takes off his shoes and socks) and thinks of cinema as static , he also suggests movies in the future will be supplied on demand; Spielberg is, as expected of a high-grossing Hollywood film-maker, interested in budgets and their effect on smaller films, though he is generally buoyant about the future of cinema; while Monte Hellman isn’t, hates dumb films and tapes too many movies off TV he never watches; all of which is undercut by Turkish director Yilmaz Güney, who talks the damaging affects of capitalism and the reality of making films in a country where his work was suppressed and banned “by some dominant forces”.

<p><a href=”http://vimeo.com/16992326″>Wim Wenders – Room 666 (1982)</a> from <a href=”http://vimeo.com/user5262516″>Cpá TV</a> on <a href=”https://vimeo.com”>Vimeo</a>.</p>Via The World’s Best Ever and Dangerous Minds