Category: Essay

‘World Cinema and the Essay Film’ Conference: Keynote by Prof Timothy Corrigan

Organised by the University of Reading’s Centre for Film Aesthetics and Cultures (CFAC), the ‘World Cinema and the Essay Film’ conference (30 April – 2 May 2015) featured Prof Timothy Corrigan’s (University of Pennsylvania) keynote address on ‘Essayism and Contemporary Film Narrative’, in which he describes how the mode of essayist becomes more and more frequently a disruptive force in narrative films such as Tree of Life (Malick 2011) or The Mill and the Cross (Majewski 2011).

Timothy Corrigan is a Professor of English and Cinema Studies at the University of Pennsylvania. He received a B.A. from the University of Notre Dame, and completed graduate work at the University of Leeds, Emory University, and the University of Paris III. Books include The Films of Werner Herzog: Between Mirage and History (Routledge), A Cinema without Walls: Movies and Culture after Vietnam (Routledge), New German Film: The Displaced Image (Indiana UP), Film and Literature: An Introduction and Reader (Routledge), The Film Experience (Bedford/St. Martin’s), Critical Visions: Readings in Classic and Contemporary Film Theory (Bedford/St. Martin’s, both co-authored with Patricia White), American Cinema of the 2000s (Rutgers UP), and The Essay Film: From Montaigne, After Marker (Oxford UP), winner of the 2012 Katherine Singer Kovács Award for the outstanding book in film and media studies.

Prof Corrigan’s keynote speech abstract ‘Essayism in Contemporary Film Narrative‘

The essay, the essayistic, and essayism represent three related modes that, at their core, test and explore subjectivity as it encounters a public life and subsequently generates and monitors the possibilities of thought and thinking. The first is a semi-generic product, the second an intervention, and the third a kind of knowledge. The relation of each to other practices, such as narrative, is largely a question of ratios: as assimilative, as inflective, or as disruptive. My title obviously draws on the third mode, and aims to describe and argue a way in which the heritage and distinctions of the essay take a different form than those described more essentially by the essay film. Here, essayism becomes more and more frequently a disruptive force and presence within the presiding shape of a film narrative, a disruption that questions, at its heart, the limits and possibilities of film narrative itself. Specifically and too schematically, essayism questions the interiority of film narrative 1) through the disintegration of narrative agency as a singular and coherent figure, 2) through the exploration of the margins of temporality and history (as a realism) in a movement into unsheltered and “improbable” places, and 3) through the questioning of the knowledges that have conventionally sustained narrative. My two examples will be Terrence Malick’s Tree of Life and Lech Majewski’s The Mill and the Cross, both released in 2011, both engaged with and questioning–not coincidently I think–a dominant Judeo-Christian narrative as the foundation of knowledge, and both operating on the edges of conventional narrative form.

Timothy Corrigan University of Pennsylvania

Date: 30 April – 2 May 2015

Venue: Minghella Building, Whiteknights Campus, University of Reading

Conference convenor: Dr Igor Krstic

ARDECHE IMAGES – Les États généraux du film documentaire 17th-18th Aug 2015

Fragments of a filmmaker – Marc Karlin

Marc Karlin (1943-1999) belongs to that generation of filmmakers who, after having gone through the militant experience of the sixties and seventies, developed a new political filmmaking praxis in the eighties (the years of Margaret Thatcher and Ronald Reagan) by rethinking and moving beyond the Marxist tradition. His political activism expressed itself in a radical approach to documentary aesthetics and a constant attempt to build an alternative film culture in opposition to the media system – he was the editor and publisher of an independent film journal, Vertigo, founded in 1993. From Nightcleaners Part 1 (1972-75), made as a member of the Berwick Street Film Collective, Karlin saw the film form as a mirror of the revolutionary process: aesthetics had to be as radical as politics. All the rushes of the film, too similar to a classical agit-prop documentary, were completely deconstructed using the optical printer and the editing: the result was a complex avant-garde film about the contradictions of militant thinking and the women’s struggle for rights and union recognition. The discrepancies of militant cinema were inscribed directly in the film language and its materiality: this was the trademark of Karlin’s future work. In the eighties and nineties, Karlin made twelve films: he benefited from the new challenges and openings in television made possible by Channel 4 and he carved out a space that left uncompromised his political vision. The film form that Karlin thought about and refounded is the essay film: a hybrid form, open to political actuality (the revolution in Nicaragua for example), simultaneously turning to the past – considered as an archive of the oppressed – and towards the future – considered as a utopian promise. This hybrid form assembled elements from the archive (making visual metaphors and conceptual short circuit), arguments and quotations (a multi-layered literary voicing and a fragmented narrative), and an elegant visual choreography (camera tracking through space and time). At the beginning of the decade of the ascending neoliberalism, the age of oblivion, Karlin made For Memory (1982), an unorthodox portrait of capitalism, the growing of cultural amnesia and the tyranny of memory: the act of remembering is shown as an interrogation of the future and as a walk through the British revolutionary tradition – John Milton and the Levellers. Disappointed by the times he was living in Europe, Karlin, an internationalist socialist, was immediately interested in the Nicaragua revolution (that began in 1979 with the end of Somoza’s regime) and he decided to make a series of films about this challenging process. The starting point was a photobook made by Susan Meiselas: Voyages (1985) was the first of a four parts series that found a coda in 1991 with Scenes for a Revolution. Karlin never made a triumphant portrait of the country and never interviewed the main Sandinista leaders, as he wanted to be with the ordinary Nicaraguan people, filming from the roots and not from the top of the country. For each part of the project he invented and adjusted a dialectical film form in order to reveal all the daily beauty and the hard contradictions of the revolution. The five Nicaraguan films are not effective political or propaganda tools, nor ideological manifestos; they are subtle thinking forms about real struggle and real people. The following part of Karlin’s research about revolution was Utopias (1989), a melancholic and pensive essay about the crisis and the heritage of the left. Utopias was Karlin’s response to Margaret Thatcher’s claim that socialism was dead: the film is structured around an imaginary banquet where six guests, from different factions of the left are invited to debate the relevance of the socialist project for their own life’s work. If Utopias was about the past of the left, Between Times (1993) was a kind of a bitter coda made to imagine the future of the revolutionary tradition. After the collapse of the Soviet system and the birth of Tony Blair’s New Labour, Karlin was trying to make a film not about definitions, but an invitation to think about the possibility to find a place for the word “us” in the current political vocabulary and to build a possible resistance to barbarity. When Marc Karlin died, in 1999, The Independent wrote that he “was the most significant, unknown filmmaker working in Britain during the past three decades”: his work is now rediscovered, and we see it as an important missing figure in the documentary film history, the lost-and-found link between militant and experimental cinema.

By Federico Rossin

Partnered with the Marc Karlin Archive – Hermione Harris, Holly Aylett and Andy Robson.

Debates led by Federico Rossin – 17th-18th Aug 2105

See here for full schedule.

Red Wedge Contact Sheet with Porky the Poet.

Found in between a folder marked ‘various’ in the archive, were a couple contact sheets from the days of Red Wedge in the mid 1980s. Those faces captured include a young Phil Jupitus or rather, his performance name at the time, Porky the Poet.

Jupitus toured colleges, universities and student unions, supporting bands such as Billy Bragg, the Style Council and The Housemartins. He supported Billy Bragg once more on the Labour Party-sponsored Red Wedge tour in 1985: In the early ’80s, I got involved with Red Wedge, in which Neil Kinnock got various bands to stage concerts for Labour. The reason I got involved was 20% because I believed in the cause, 30% because I loved Billy Bragg, and 50% because I wanted to meet Paul Weller.

In a interview with the Guardian, Pieces of Me, in 2008, where guests are asked to reflect on objects from their past, Jupitus presents his Red Wedge access all areas badge and says, This [pro-Labour musicians’ collective] Red Wedge pass reminds me of how optimistic I was about socialism. I can’t stand what happened to the Labour party – it’s so sad.

Here is Porky the Poet in action with some minor use of the f word.

Red Wedge was formed in the lead up to the 1987 general election. A group of musicians and comedians grouped together hoping to engage young people in politics, in an effort to force out Margaret Thatcher’s Conservative Party from power.

Fronted by Billy Bragg (whose 1985 Jobs for Youth tour had been a prototype of sorts for Red Wedge), Paul Weller and The Communards lead singer Jimmy Somerville, they put on concert parties and appeared in the media, adding their support to the Labour Party campaign.

The group was launched on 21 November 1985, with Bragg, Weller, Strawberry Switchblade and Kirsty MacColl invited to a reception at the Palace of Westminster hosted by Labour MP Robin Cook.

The collective took its name from a 1919 poster by Russian constructivist artist El Lissitzky, Beat the Whites with the Red Wedge. Despite this echo of the Russian Civil War, Red Wedge was not a communist organisation; neither was it officially part of the Labour Party, although it did initially have office space at Labour’s headquarters. The group’s logo also took inspiration from the Lissitzky poster, designed by Neville Brody.

Red Wedge organised a number of major tours. The first, in January and February 1986, featured Bragg, Weller’s band The Style Council, The Communards, Junior Giscombe, Lorna Gee and Jerry Dammers, and picked up guest appearances from Madness, The The, Heaven 17, Bananarama, Prefab Sprout, Elvis Costello, Gary Kemp, Tom Robinson, Sade, The Beat, Lloyd Cole, The Blow Monkeys and The Smiths along the way.

When the general election was called in 1987, Red Wedge also organised a comedy tour featuring Lenny Henry, Ben Elton, Robbie Coltrane, Craig Charles, Phill Jupitus and Harry Enfield, and another tour by the main musical participants along with The The, Captain Sensible and the Blow Monkeys. The group also published an election pamphlet, Move On Up, with a foreword by Labour leader Neil Kinnock.

After the 1987 election produced a third consecutive Conservative victory, many of the musical collective drifted away. A few further gigs were arranged and the group’s magazine Well Red continued, but funding eventually ran out and Red Wedge was formally disbanded in 1990.

More reading on Red Wedge.

http://www.theguardian.com/stage/gallery/2008/jun/23/comedy.television

http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/entertainment/music/3682281.stm

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Red_Wedge

https://vintagerock.wordpress.com/2014/03/30/red-wedge-tour-newcastle-city-hall-31st-january-1986/

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Phill_Jupitus

Patterns and Connections – Editor, Brand Thumin on Marc Karlin.

Each film that Marc Karlin directed during the period in which I worked with him was on a grand scale, predominantly documentary in nature, and with strong poetic elements. Each was largely or completely financed by television.

For me, the reasons why they were totally engrossing to work on are the same reasons why they are fascinating to look at now.

The films were always about major subjects, always undertaken on account of something that Marc was deeply affected by, something that he became preoccupied with almost to the point of obsession, something he felt passionately about – never for any other reason.

He was constantly reflecting on what was going on around him and in the world at large. The TV series Holocaust, and the nature of its reception all over the world, appalled him and provoked him into thinking about the themes and ideas that were to become the subject of For Memory. While visiting Hermione Harris in Nicaragua, he was astounded by what he saw taking place there and this led him to make a series of four films of great clarity and complexity, four distinct parts of an epic whole. Then, back in Britain, came Utopias, Marc’s response to the endlessly repeated assertion that socialism was dead.

Marc was like an explorer. Each time he began work on one of these films he was like someone embarking on a journey, taking a group of people with him. Each collaborator was essential to the different stages of the journey. The films explored ideas, themes, histories, and physical realities. They drew portraits and told stories. They also explored the forms of documentary film, continuing and developing the work of the preceding films.

Marc knew how to draw vital contributions from all his collaborators at every step of the way. He directed them, and at the same time demanded their input. He knew how to channel other people’s creative energies into the enterprise.

When we were editing together, he wanted me to contribute, rather than carry out his plan. He wanted me to bring my mind to bear on the material, on what the film proposed to accomplish, to do some of the exploring in that phase of the making of the film. He directed the editing in such a way as to draw me into doing this. The editing had to be both descriptive and reflective, it had to convey ideas and themes as much as it had to portray concrete realities. It had to allow the viewer to make multiple connections between these things. And it had to bring out the lyrical and sensual aspects of the images and sounds. The juxtaposing and interweaving required to achieve this is one of the things I enjoy most about editing, and as Marc and I had the same sense of what needed to be done, we worked together very harmoniously.

Looking at these films now, years later, it seems to me that one of the things that makes them so singular is this constant and multiple interconnecting and interrelating of ideas and individual concrete realities. Here are films with grand themes, in which the individual lives and characteristics of the people who appear in them have as much weight as the ideas they are related to, so that each contains vivid portraits of individual people. Marc was as passionate about individuals as he was about ideas, and this was evident at every stage of the making of these films. I was conscious of it during the editing and I can see it in the films now.

Brand Thumim worked as editor for Marc Karlin between 1980 and 1988 on the films For Memory, Nicaragua parts 2, 3 and 4, and Utopias.

Marc Karlin and Cinema Action 1968-1970

Promotional Material from Cinema Action’s Rocinante – found in the archive.

Last week in the BFI’s Essential Experiments slot, William Fowler presented the work of the filmmaking collective, Cinema Action. Two films were screen from the collective’s vast filmography – Squatters (1970), an attack on the Greater London Council regarding their lack of investment in housing . The film provided important – if controversial – information about the use of bailiffs in illegal eviction. And So That You Can Live (1981) which is widely recognised as one of Cinema Action’s finest works. The film follows the story of inspiring union convenor Shirley and the impact global economic changes have on her and her family’s life in rural South Wales. The landscape of the area, with all its complex history, is cross-cut with images of London, and original music from Robert Wyatt and Scritti Politti further reinforces the deeply searching, reflective tone. It was also broadcast on Channel 4’s opening night in November 1982.

Here is a history of Cinema Action via the BFI’s Screenonline

Cinema Action was among several left-wing film collectives formed in the late sixties. The group started in 1968 by exhibiting in factories a film about the French student riots of that year. These screenings attracted people interested in making film a part of political activism. With a handful of core members – Ann Guedes, Gustav (Schlacke) Lamche and Eduardo Guedes – the group pursued its collective methods of production and exhibition for nearly twenty-five years.

Cinema Action‘s work stands out from its contemporaries’ in its makers’ desire to co-operate closely with their working-class subjects. The early films campaigned in support of various protests close to Cinema Action‘s London base. Not a Penny on the Rent (1969), attacking proposed council rent increases, is an example of the group’s early style.

By the beginning of the seventies, Cinema Action began to receive grants from trades unions and the British Film Institute. This allowed it to produce, in particular, two longer films analysing key political and union actions of the time. People of Ireland! (1971) portrayed the establishment of Free Derry in Northern Ireland as a step towards a workers’ republic. UCS1 (1971) records the work-in at the Upper Clyde Shipyard; it is a unique document, as all other press and television were excluded.

Both these films typify Cinema Action‘s approach of letting those directly involved express themselves without commentary. They were designed to provide an analysis of struggles, which could encourage future action by other unions or political groups.

The establishment of Channel Four provided an important source of funding and a new outlet for Cinema Action. Films such as So That You Can Live (1981) and Rocking the Boat (1983) were consciously made for a wider national audience. In 1986, Cinema Action made its first fiction feature, Rocinante, starring John Hurt.

Marc Karlin joined Cinema Action in 1969. He had just returned to London after being caught up in the events of May ’68 in Paris while filming a US deserter. It was there where Karlin met Chris Marker, who was editing Cine-Tracts (1968) with Jean-Luc Godard at the time. Marker had just formed his film group SLON and had since released Far from Vietnam (1967), a collective cinematic protest with offerings from Jean-Luc Godard, Alain Resnais and Agnes Varda, inspired by the film-making practices of the Soviet film-maker, Alexander Medvedkin. The idea of taking this model of collective filmmaking back to the UK appealed greatly to Karlin, and was shared by many of his contemporaries. He details this enthusiasm in an interview with Sheila Rowbotham from 1998…

…when Marker started SLON, ideas about agitprop films were going around. Cinema Action had already started in England by 1969 when I joined. There was a relationship to the Russians: Vertov, the man with a movie camera, Medvedkin and his Russian agitprop train; the idea of celebrating life and revolution in film, and communicating that. Medvedkin had done that by train. SLON and Cinema Action both did it by car. Getting a projector, putting films in the boot, and off you went and showed films – which is what we did…

…when I joined there was no question of making documentaries for television. We showed our films at left meetings, where we would set up a screen, do leaflets and so on. It is often hilarious. I remember showing a film on housing in a big hall in the Bull Ring area of Birmingham. It started with machine gun noises, and Horace Cutler, the hated Tory head of the Greater London Council, being mowed down. The whole place just stopped and looked, but, of course, as soon as you got talking heads, people arguing or living their ordinary lives, doing their washing or whatever, we lost the audience. I learnt something through seeing that.

Evidently, Karlin was frustrated about the political and aesthetic approach of Cinema Action. In fact, salvaged in the archive is two thirds of a letter written by Karlin to Humphry Trevelyan that goes into some detail over the reasons for why Karlin intended to leave Cinema Action. For now, here is Karlin giving a somewhat exaggerated reason for leaving in the interview with Rowbotham…

…Schlacke (Cinema Action co-founder) had a thing about the materialist dialectic of film. Somehow or other – and I can’t tell you how are why – this meant in every eight frames that you had to have a cut. Schlaker justified this was some theoretical construct, but it made his films totally invisible. After a time I just got fed up. James Scott, Humphry Trevelyan and I started The Berwick Street Film Collective and later went on to join Lusia Films.

The Berwick Street Film Collective’s Nightcleaners (1975)

Find out more about the figures involved in Cinema Action and other British film collectives.

And…

Looking at Class. Film, Television and the Working Class in Britain, S, Rowbotham & H, Beynon, (Rivers Oram Press:2001)

Cinema Action – Steve Sprung – He Wanted to Make Movies the Way Everybody Else Does!

Tonight at the BFI, Southbank sees a celebration of the work of the film collective, Cinema Action. After a screening of Squatters (1970) and So That You Can Live (1981), Ann Guedes and Steve Sprung, Cinema Action members, will be present for a Q&A.

Steve Sprung was a key collaborator with Marc Karlin on five films and later contributed to the book Marc Karlin – Look Again.

Here is Steve’s article on Karlin from the summer of 1999. It featured in an issue of Vertigo magazine dedicated to Karlin, who died in the January of that year.

It’s hard to imagine it, the idea of Marc turning in his grave, but surely he must have. May Day… Saturday the first, not Bank Holiday Monday.

Nothing to do with his beloved Arsenal, but with that other, mostly negative, mover of his being, television. In a programme hosted by Jon Snow the British people were allegedly invited to make a late but vitriolic judgement on Margaret Thatcher’s seventeen years in government.

I imagined the rage it would have elicited from Marc – not against the obvious target, Thatcher and her die-hard crew – but against all those claiming it was Maggie who done it, that this she-devil incarnate must now take all the blame. At a time when cleansing, by all manner of powers over other powers, dominates our television screens, this was an equally crude wiping clean. Television’s refusal to engage with the complex process of those years – years which constitute a substantial chunk of our adult lives as well as moulding future generations – would have had him livid.

It was this Thatcher period which formed the context for my work with and for Marc. My background had been in a more agitational cinema, but I had been struggling for years, labouring away in the basement under Lusia Films, with a film about a failed strike under the previous Labour government, and its role in laying the ground for the Thatcherism that was to come. How to talk about events which had been mischaracterised both by the dominant media industry and by the working classes’ own trade union and political organisations? How to reveal this massive content, tell this necessary story, and find an adequate form in which to do it?

This film, The Year of the Beaver, finally emerged in the early eighties. It manages to create multiple layers of meaning, drawing connections between the myriad things it had been necessary to take on board. When he saw it, Marc hugged me. This, I felt, was our first real meeting. On looking again at Marc’s early films, I came to realise they had always been about looking beneath the surface to reveal connections. In a sense they are films which try to open up for the viewer the process we went through as filmmakers, inviting them, as far as was possible, to share the journey we had made. Thus they were films which interrogated their audiences as much as they interrogated their subject-matter, just as we had interrogated ourselves as part of their making.

I worked on five films with Marc. I was one of many with whom he talked at great length about the ideas underpinning each new project. We would try out sequences with video-cameras, and these I would cut and re-cut, often summoned to Lusia by a Saturday morning ’phone call.

I chose not to attend the actual shoots (on 16mm) so that I could come to the rushes with as fresh an eye as possible. It was as if the material had been encircled, caught by the camera. Now the ideas, and the film which would bear them, had to be re-discovered, and brought to life on the editing table.

The Outrage, 1995

Marc, insecure as he was, as we all are when laying ourselves on the line and taking risks to say more than we readily know how to say, was incredibly secure in terms of entrusting me with the material. When viewing my cuts, he had the sharpest eye for detail, and its relationship to the whole, but he gave me unhindered space in which to work. He never demanded that this or that shot must be used, and was in this sense able to subsume his ego to the film.

Why?

Because the films were about something bigger than Marc or any of us who worked on them, and we were simply engrossed in trying to understand how to bring the ideas to life.

Paradoxically perhaps, the first film I edited with Marc was the last of his more conventionally “political” and “documentary” works.

Between Times was a journey through the countervailing political ideas of the “in between times” he felt we were in, and through the sort of questions Marc felt this period posed for anyone still concerned with bringing about revolutionary change. I’ll always remember the end of the film: the two protagonists, who’d been conducting an argument by presenting various documentary stories, were revealed to be one single, contradiction-filled person. But this was a person who held on to a simple truth: when we had none of the technology to construct a new world we had the capacity to dream it; now that we had the technology, we seemed to have lost the capacity to dream the dream.

Between Times was a turning point in his and our filmmaking. Marc moved towards the politics of culture and away from films whose legitimacy derived from concrete documentary material based on ongoing political action. He went for a new type of direct cinema, looking at how the world is culturally constructed and by whom, and exploring the blockages preventing perceptions of the world which are different from those of the more dominant vision.

The Outrage, 1995

This required a different use of the material basic to documentary filmmaking, an approach which freed itself from following the sequence of particular events or political actions. It was an approach I had begun to explore in a film I had recently co-directed, Men’s Madness, and something which Marc’s practice, and his work with people such as Chris Marker, had enabled him to appreciate. He saw it as a step forward in opening up the political space of cinema, and he continued to develop it further in his films, drawing increasingly on fictional and scripted elements.

In The Outrage, a man goes in search of a painting, or, rather in search of the art in himself. This film shows another aspect of Marc’s work: the supposed subject of the film – in this case a portrait of the artist Cy Twombly – is turned upside down and viewed from an unexpected angle. Thus we are able to look at the subject afresh, to look at art and painting from the point of view of the viewer. We go through precisely the process of re-discovery Marc had gone through to be able to create the film. This journey we, his collaborators, had also shared, leading us to engage with that essential need which emerges as art. Not the art of the market place, but the art that most of us leave behind somewhere in childhood, in the process of being socialised into the so-called real world. The art which still yearns within us.

The Outrage contained an important sequence which talked about the role of advertising (and this includes MTV) in our visual culture. This is the one place where it is permitted for images to be freely given over to the imagination. But here imagination has become no more than a commodity, and the images bear the emptiness of this prostitution. In contrast, the richness of The Outrage’s visual imagery and the imaginativeness of its narrative form are inseparable from an equally rich and meaningful content. The film’s imagery does not flow over and mesmerise the viewer; it asks for a more complete involvement.

Marc’s next film, The Serpent, about the demonising of Rupert Murdoch, continued this rich texturing of image, sound and meanings. I’m sure Marc had experienced visions of Murdoch horned and spitting fire, but he wanted to interrogate that whole process of “demonising” which we all revel in. He wanted, crucially, to look at what it really avoids, to address the difficult political questions it allows us to duck; how to fight against a culture which apparently offers more of everything, more channels, more choices, more democracy, more freedom? and how to ask another simple, yet largely unasked, question – where are all these choices leading? Freedom to do what?

It was during the making of The Serpent that Marc introduced Milton to me and to his films, in the epic form of Paradise Lost. This poem had obsessed him for some considerable time. It speaks of the devil not from a moral perch, nor of him as a foreigner, but as being resident somewhere in all of us. It was more than the text, however, that was rhyming with us. Just as Milton became isolated in his lifetime through his constant search for illumination, labouring to understand why the revolution of his time had failed, so we too were destined to a similar isolation. We had made ourselves outsiders by virtue of our way of working, by the endeavour of Marc’s kind of filmmaking. Perhaps this was the only place we could be. We required an audience who wished to make a journey similar to ours, whereas we live in a society in apparent need of constant triviality, one afraid to take itself too seriously for fear of what it might uncover, and desirous of seemingly “entertaining itself to death”. Perhaps this is the message of Murdoch’s easy victory.

The Outrage, 1995

This experience of being outside, witnessing a culture whose memory is in a dangerous state of decay, provided the impetus for The Haircut (a short about the cultural conformity of New Labour) and for Marc’s last work in progress on Milton: A Man who Read Paradise Lost Once Too Often.

Marc was preparing to keep up the fight. Coming from a different space, I had my reservations. The references that resonated for him were different from mine. I also knew he was engaged in a holding operation, perhaps one which few would be able to understand.

The film was not to be.

I can remember a sense amongst many of us present in the pub after Marc’s funeral of this being the end of an era. Would there be space in future for his kind of work? Where would it find its funding?

It seems to me there is an equally important question before us: will we be able, as time goes by, even to conceive of such work? It requires a skill that can only be developed through practice, and a great deal of time – gestation time and, especially, post-production time.

Marc’s are films about a process, and thus they have an organic life to them. They were not made with an eye to filling a television slot, but were designed to take the time they needed to take to communicate the exploration they had undertaken. This is why their significance lingers on beyond the momentary blip they represented in the continuous present that is television, and why they will outlive their own time. They are representations of the complex processes by means of which we come to understand who we are, where we are and what we are.

Steve Sprung is a film director and editor.

Vertigo Volume 1 | Issue 9 | Summer 1999

Video Essay – Marc Karlin

The Marc Karlin Collection is now available to stream and download on Vimeo On Demand.

Look Again #2 – Hugh Stewart

Imperial War Museum – Hugh Stewart

In the lead-up to the release of Marc Karlin-Look Again here are a collection of portraits focusing on the people Karlin documented in his films.

Hugh Stewart was a film editor and latterly a film producer. After graduation from college he joined Gaumont-British Picture Corporation on an apprenticeship scheme working as an assembly cutter. After impressing Alfred Hitchcock, he was asked to supervise the edit on The Man Who Knew Too Much (1934). Speaking in 1999, Stewart recalls the the production,

When he (Hitchcock) came on stage for the first day of shooting, he put the script down and said, “Right, another one in the bag.” Not that he had any disrespect for the making of the film, but as far as he was concerned, he knew the film so well, it was already in his mind. The Albert Hall sequence was the major example of it.

In the story the mother, Edna Best, went to a concert at the Albert Hall. As she sat there she realised that an assassin was going to kill an ambassador sitting in the Royal Box. The assassin had also stolen her child, so she was there with a double purpose. The words of the chorale being performed included the phrase “Save the Child,” which was an ingenious underlining of the second motif which was in her mind, though not in the visible action. Hitchcock made a variety of shots, and the author had the task of piecing them together, using the music as a frame-work.

And here Stewart recalls his editing work on a Michael Powell production. A similar occasion had arisen during the making of “A Spy in Black,” a good film made by Michael Powell in 1938. A German “U” Boat, with Conrad Veidt as Captain, was making its way through a minefield outside the Orkneys. The quality of suspense was very necessary, so a few chart inserts were shot, some underwater submarine shots were found, and a delightful couple of days were spent working up a sequence.

When war broke out in 1939, he immediately joined the Royal Artillery. He was commissioned in the AFPU (Army Film and Photographic Unit) in December 1940 and led No 2 AFPU in covering the Allied landings in Tunisia in November 1942. A year later he co-directed Tunisian Victory (1943) with John Huston and Frank Capra.

Later, as head of No 5 AFPU, Stewart and his combat cameramen covered the British D-Day landings, the Caen breakout, the Rhine Crossing and the Battle of the Ardennes — as well as the liberation of Bergen-Belsen.

When Belsen was voluntarily turned over to the Allied 21st Army Group on April 15 1945, Stewart was head of No 5 Army Film and Photographic Unit (AFPU). As such he was under strict War Office orders to remain with the British Army as it advanced further into Germany. But realising the significance of the scenes at the camp, he decided to go over the heads of his superiors and make a direct appeal to Eisenhower, arguing that it was vital to prepare a cinematic and photographic record.

Eisenhower overrode the War Office, and in the days after the liberation Stewart and his team undertook the harrowing job of filming the camp. Towards the end of his life Stewart said that not a single day had gone by without him remembering by sound, sight and smell of what he witnessed during those few days. Later he was consulted by the research team for Steven Spielberg’s Schindler’s List (1993).

Before contributing to Schindler’s List production, Hugh Stewart appeared in Marc Karlin’s For Memory (1982) co-produced by the BBC and BFI. It was a film about the fragility of memory. Ironically, this film about memory was forgotten by BBC, only being broadcast at a sleepy Easter slot in 1986. Karlin had been extremely unnerved by the miniseries Holocaust (1978), Hollywood’s serialisation of the genocide starring Meryl Streep and James Woods, portraying the (fictional) Weiss family of German Jews. Karlin found the series an offensive account of the holocaust, writing in his notebook: how could a documentary photograph die so soon and be taken over by a fiction?

This line of thought is expanded upon in an extract from For Memory’s commentary,

For some, ill-prepared to deal with the transformation of a sacred memory into a fictional melodrama, the images of Holocaust were a desecration, the betrayal of what had been considered an untouchable testimony to those events. But for others, these new reminders were the best that could be done to save these memories from the threat of oblivion. In the space of one generation, photographs and documents were judged to be no longer able to carry the weight of the events they once portrayed.

Marc Karlin approached Hugh Stewart, together with his AFPU camera Joe Perry, in 1980 and asked them to recount exactly what they could remember about that day in 1945.

For Memory begins, like other Karlin films, a fade in on a subject, without caption or a guiding voice-over.

Further Reading

http://the.hitchcock.zone/wiki/Hugh_Stewart

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hugh_Stewart_(film_editor)

http://www.altfg.com/blog/movie/hugh-stewart-death-film-editor-hitchcock/

Look Again #1 – Marsha Marshall

In the lead-up to the release of Marc Karlin-Look Again here are a collection of portraits focusing on the people Karlin documented in his films. Up first is Marsha Marshall, secretary of the Women Against Pit Closures (Barnsley Group) during the 1984-85 Miners’ Strike.

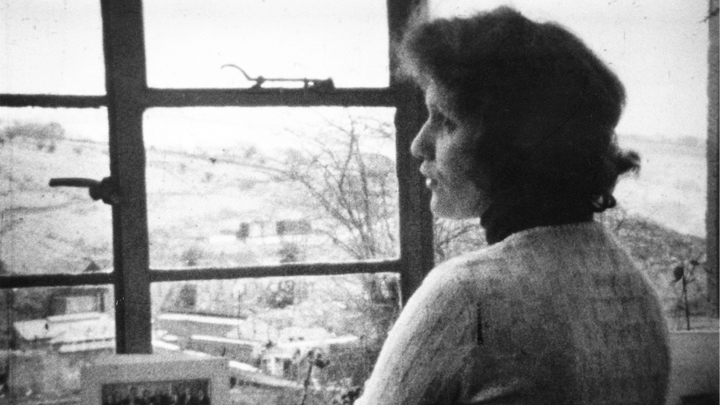

Marsha Marshall circa 1986 ©The Marc Karlin Archive

Marsha Marshall, who died in April 2009, lived with her miner husband, Stuart ‘Spud’ Marshall, in Wombwell, near Barnsley at the time of the 1984/84 Miners Strike. Spud was one of the first to be arrested during the dispute on a picket line in Nottinghamshire. This event politicised Marsha, and soon with others she founded the Women’s Against Pit Closures. Having never been abroad before, her duties as secretary of the WAPC, took her to France, Italy, Bulgaria, and the USSR – and in Rome she spoke at a rally to over 4,000 Italian trade unionists.

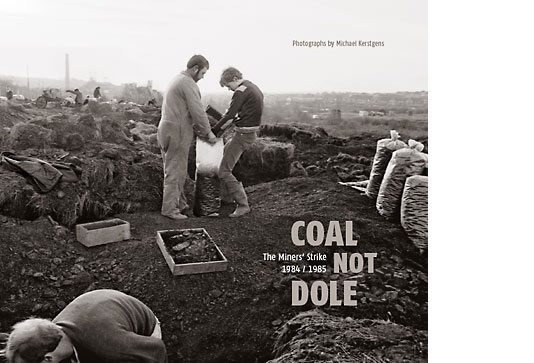

Marsha is featured in Michael Kerstgens’ photographic collection, Coal Not Dole, The Miner’s Strike 1984/85 published by Peperoni Books. In 1984, Michael Kerstgens was a young German photography student who decided to travel to Britain and document the dispute. People were wary of him, as an outsider, and so he was limited to photographing events on the periphery.

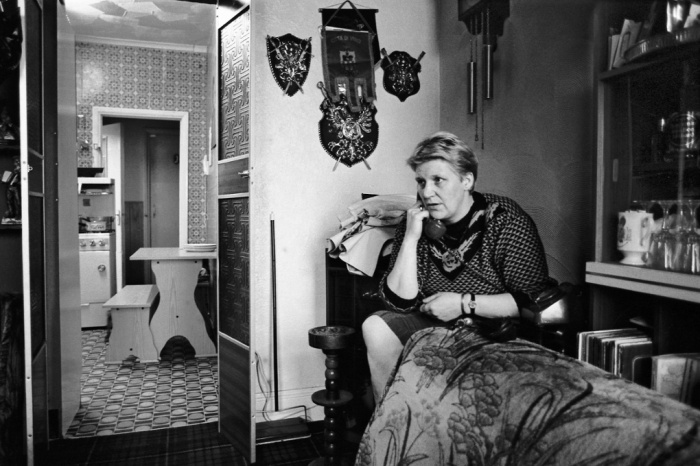

However, things changed when he met the activist Stuart “Spud” Marshall. Spud trusted him immediately and opened the door for Kerstgens to photograph not only the heat of the action but also more intimate moments beyond the picketing, violent clashes with the police, and public discussions on the political stage. Kerstgens photographed soup kitchens, meetings behind closed doors, and the wives of striking miners, including Marsha.

Marsha Marshall supports picketing miners with a donation of cigarettes. © Michael Kerstgens

Marsha Marshall on the telephone to Vanessa Redgrave, Wombwell, 1985, © Michael Kerstgens

Around 1986, Karlin interviewed Marsha Marshall for his film ‘Utopias’ – a film about socialism in Britain, broadcast on Channel 4 in 1989. Marsha would be one of the socialist voices in his film. Karlin, here, recalls his creative intentions,

I was filming Utopias in 1986, around the time Margaret Thatcher said she aimed to destroy socialism once and for all. I was determined to say otherwise, obviously. I wanted to do portraits of different socialism, take ideas about it and so on, but to put them all on one boat. Utopias was like a banquet table. I liked the idea of having somewhere all these people could be together, where David Widgery, Sheila Rowbotham and Jack Jones, Sivanandan, Bob Rowthorn, and the miner’s wife, Marsha Marshall, were all going to be there. All these visions of socialism were great. I am totally naïve, but I shall remain to the end, so I just wanted them all at the table. Can you imagine? No: But the film did.

Marc Karlin and Marsha Marshall, circa 1986, ©The Marc Karlin Archive

This is an edited extract of Marsha’s chapter from ‘Utopias’. In this section she recalls the miners’ strike and speaks about her fears for the future of her community.

‘Spud’ Marshall at home in Kendray Barnsley, September 2012 © Michael Kerstgens

Further Reading –

Coal Not Dole, The Miners’ Strike 1984/1985, by Michael Kerstgens, is published by Peperoni Books

http://peperoni-books.de/coal_not_dole00.html

http://www.southyorkshiretimes.co.uk/news/local/strike-hero-marsha-dies-at-64-1-615649

Looking at Class. Film, Television and the Working Class in Britain, S, Rowbotham & H, Beynon, (Rivers Oram Press: 2001)

‘Utopias’ – Part 1. Opening Sequence A/V Script

Utopias’ Treatment ©The Marc Karlin Archive

(Music) Edward Elgar-Cello Concerto in E minor

V/O (Archive) Socialism is a very attractive idea and could remain a very attractive idea so long as there were not many,at best none, socialist governments.

V/O (Archive) If you begin to tamper with economic freedom, you find it doesn’t work very well, therefore you have to go further and impose further controls on the economic activities in order to get the result you want. And in doing that you run up against increasing resistance from ordinary people and in order to beat down that resistance you have to limit their political freedoms too.

V/O (Archive) It is hard to access the damage the welfare state has done in Britain to the spirit of independence and social conventions that impel people to overcome their own poverty.

V/O (Archive) Socialism and social democracy according to Schneider’s Objectivism beliefs soften the play of competition by forcing people to share their wealth with others through taxation. V/O (Archive) I think greed, as a matter of fact, lead us by an invisible hand to a welfare state because the truly greedy man wants comfort and security, and he ordinarily partitions government to give it to him. The capitalist wants challenge and creativity. V/O (Archive) You can compare practice to practice, there’s no competition. Capitalism is completely overwhelming socialism.V/O (Marc Karlin) The one crisis Socialists were not able to predict was their own. Socialism once thought of being inevitable is now replaced as a socialism that is remote, at best half remembered. Unable to state confidently a vision of the future, yet in the name of renewal and adaptation, impatient to shed its past.

V/O (Marc Karlin) Everyone speaks about socialism as if we all know what it is – for it or against it. When people are saying farewell to socialism, this is a film about what it is they are saying farewell to, a series of portraits of individuals and their ideas one might encounter on a journey through the life of socialism in Britain today.

V/O (Marc Karlin) The film is not about definitions it is more an invitation to see whether there is still a place for the word us in the current political vocabulary.

Channel 4 broadcast ‘Utopias’ on Monday 1st May 1989 at 10.45pm.