Category: Video

Mary Kelly – Conceptual Artist + Berwick Street Film Collective filmmaker on Nightcleaners (1975) – TateShots

American conceptual artist Mary Kelly discusses how feminism informed her seminal work Post-Partum Document 1973-79 and the origins of her lint technique.

Mary Kelly arrived in London as a student at a time when the public began to protest contentious political issues like gender equality and the Vietnam War. She became involved in the early women’s liberation movement throughout the 1970s and went on to lead the way for representations of women in the arts.

Feminist theory, political discourse and education have remained a constant theme in her work throughout her career. Her work Post-Partum Document 1973-79 draws on contemporary feminist thought and psychoanalysis to explore the roles of woman artists as both creative and procreative.

More recently, Kelly has developed a process where she creates various sizes of prints cast from units of lint, the textile fibres that separate in a domestic dryer. Fashioned over several months and hundreds of washing cycles, the panels of image and text are then assembled and pressed in intaglio.

Mary Kelly is Professor of Art at the University of California, Los Angeles, where she is Head of Interdisciplinary Studio.

Also, here is Mary Kelly in conversation with Hans Ulrich Obrist.

As part of the curated conversation programme On the Passage of a Few People Through a Rather Brief Period of Time, Mary Kelly talks to curator, critic, art historian and prolific writer Hans Ulrich Obrist as they explore what defines an era.

John Akomfrah on the ‘border of cinema’ and the archive

John Akomfrah talks to TateShots about his practice as a filmmaker. The artist discusses how he navigates between the gallery and cinema, what compelled him to make his 2015 work Vertigo Sea, and the influence of Andrei Tarkovsky.

After a tour of his work space at Smoking Dogs, he responds to subjects such as, ‘the border of cinema’, whether he prefers working in film, TV or the gallery, the philosophy of montage, why history matters, and archive and documentary…

…the thing I have spoken a lot about is the how much the archive is a sort of memory bank, which connects it with questions of mortality. Usually at archives you can’t watch stuff without realising that it is also watching people who have gone. That recognition is on it’s own is not very much unless it is married with a second recognition which is that the image is one of the ways in which immortality is enshrined in our pysche and in our lives, you know? And documentaries do that. You make a documentary to both capture something that’s going to die unless it’s captured, but you are also trying to capture something because you want it to live…

John Akomfrah’s essay on Marc Karlin, Illumination and the Tyranny of Memory, can be seen in Marc Karlin – Look Again, edited by Holly Aylett, published by Liverpool University Press. Available now at the BFI shop.

Red Wedge Contact Sheet with Porky the Poet.

Found in between a folder marked ‘various’ in the archive, were a couple contact sheets from the days of Red Wedge in the mid 1980s. Those faces captured include a young Phil Jupitus or rather, his performance name at the time, Porky the Poet.

Jupitus toured colleges, universities and student unions, supporting bands such as Billy Bragg, the Style Council and The Housemartins. He supported Billy Bragg once more on the Labour Party-sponsored Red Wedge tour in 1985: In the early ’80s, I got involved with Red Wedge, in which Neil Kinnock got various bands to stage concerts for Labour. The reason I got involved was 20% because I believed in the cause, 30% because I loved Billy Bragg, and 50% because I wanted to meet Paul Weller.

In a interview with the Guardian, Pieces of Me, in 2008, where guests are asked to reflect on objects from their past, Jupitus presents his Red Wedge access all areas badge and says, This [pro-Labour musicians’ collective] Red Wedge pass reminds me of how optimistic I was about socialism. I can’t stand what happened to the Labour party – it’s so sad.

Here is Porky the Poet in action with some minor use of the f word.

Red Wedge was formed in the lead up to the 1987 general election. A group of musicians and comedians grouped together hoping to engage young people in politics, in an effort to force out Margaret Thatcher’s Conservative Party from power.

Fronted by Billy Bragg (whose 1985 Jobs for Youth tour had been a prototype of sorts for Red Wedge), Paul Weller and The Communards lead singer Jimmy Somerville, they put on concert parties and appeared in the media, adding their support to the Labour Party campaign.

The group was launched on 21 November 1985, with Bragg, Weller, Strawberry Switchblade and Kirsty MacColl invited to a reception at the Palace of Westminster hosted by Labour MP Robin Cook.

The collective took its name from a 1919 poster by Russian constructivist artist El Lissitzky, Beat the Whites with the Red Wedge. Despite this echo of the Russian Civil War, Red Wedge was not a communist organisation; neither was it officially part of the Labour Party, although it did initially have office space at Labour’s headquarters. The group’s logo also took inspiration from the Lissitzky poster, designed by Neville Brody.

Red Wedge organised a number of major tours. The first, in January and February 1986, featured Bragg, Weller’s band The Style Council, The Communards, Junior Giscombe, Lorna Gee and Jerry Dammers, and picked up guest appearances from Madness, The The, Heaven 17, Bananarama, Prefab Sprout, Elvis Costello, Gary Kemp, Tom Robinson, Sade, The Beat, Lloyd Cole, The Blow Monkeys and The Smiths along the way.

When the general election was called in 1987, Red Wedge also organised a comedy tour featuring Lenny Henry, Ben Elton, Robbie Coltrane, Craig Charles, Phill Jupitus and Harry Enfield, and another tour by the main musical participants along with The The, Captain Sensible and the Blow Monkeys. The group also published an election pamphlet, Move On Up, with a foreword by Labour leader Neil Kinnock.

After the 1987 election produced a third consecutive Conservative victory, many of the musical collective drifted away. A few further gigs were arranged and the group’s magazine Well Red continued, but funding eventually ran out and Red Wedge was formally disbanded in 1990.

More reading on Red Wedge.

http://www.theguardian.com/stage/gallery/2008/jun/23/comedy.television

http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/entertainment/music/3682281.stm

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Red_Wedge

https://vintagerock.wordpress.com/2014/03/30/red-wedge-tour-newcastle-city-hall-31st-january-1986/

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Phill_Jupitus

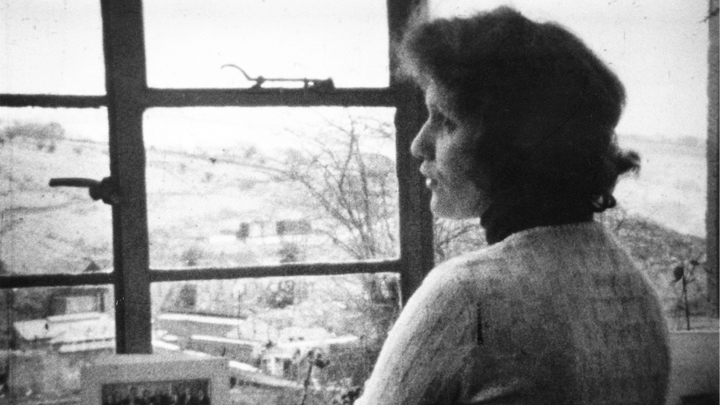

Susan Meiselas – Nicaragua – Reframing History, 2004

In July 2004, for the 25th anniversary of the overthrow of Somoza, Susan Meiselas returned to Nicaragua with nineteen mural-sized images of her photographs from 1978-1979, collaborating with local communities to create sites for collective memory. The project, “Reframing History,” placed murals on public walls and in open spaces in the towns, at the sites where the photographs were originally made.

To see the film Meiselas made with Marc Karlin, containing her original Nicaragua photographs, please view Nicaragua Part 1: Voyages on Vimeo On Demand.

Broadcast 14 October 1985 Channel 4 (ELEVENTH HOUR) (42 mins)

In 1978–79 American photographer Susan Meiselas documented the two insurrections that led to the overthrow of fifty years of dictatorship by the Somoza family in Nicaragua. Through an epistolary exchange over five unedited tracking shots across Meiselas’ photographs, the film articulates her relationship to the history she witnessed.

Patterns and Connections – Editor, Brand Thumin on Marc Karlin.

Each film that Marc Karlin directed during the period in which I worked with him was on a grand scale, predominantly documentary in nature, and with strong poetic elements. Each was largely or completely financed by television.

For me, the reasons why they were totally engrossing to work on are the same reasons why they are fascinating to look at now.

The films were always about major subjects, always undertaken on account of something that Marc was deeply affected by, something that he became preoccupied with almost to the point of obsession, something he felt passionately about – never for any other reason.

He was constantly reflecting on what was going on around him and in the world at large. The TV series Holocaust, and the nature of its reception all over the world, appalled him and provoked him into thinking about the themes and ideas that were to become the subject of For Memory. While visiting Hermione Harris in Nicaragua, he was astounded by what he saw taking place there and this led him to make a series of four films of great clarity and complexity, four distinct parts of an epic whole. Then, back in Britain, came Utopias, Marc’s response to the endlessly repeated assertion that socialism was dead.

Marc was like an explorer. Each time he began work on one of these films he was like someone embarking on a journey, taking a group of people with him. Each collaborator was essential to the different stages of the journey. The films explored ideas, themes, histories, and physical realities. They drew portraits and told stories. They also explored the forms of documentary film, continuing and developing the work of the preceding films.

Marc knew how to draw vital contributions from all his collaborators at every step of the way. He directed them, and at the same time demanded their input. He knew how to channel other people’s creative energies into the enterprise.

When we were editing together, he wanted me to contribute, rather than carry out his plan. He wanted me to bring my mind to bear on the material, on what the film proposed to accomplish, to do some of the exploring in that phase of the making of the film. He directed the editing in such a way as to draw me into doing this. The editing had to be both descriptive and reflective, it had to convey ideas and themes as much as it had to portray concrete realities. It had to allow the viewer to make multiple connections between these things. And it had to bring out the lyrical and sensual aspects of the images and sounds. The juxtaposing and interweaving required to achieve this is one of the things I enjoy most about editing, and as Marc and I had the same sense of what needed to be done, we worked together very harmoniously.

Looking at these films now, years later, it seems to me that one of the things that makes them so singular is this constant and multiple interconnecting and interrelating of ideas and individual concrete realities. Here are films with grand themes, in which the individual lives and characteristics of the people who appear in them have as much weight as the ideas they are related to, so that each contains vivid portraits of individual people. Marc was as passionate about individuals as he was about ideas, and this was evident at every stage of the making of these films. I was conscious of it during the editing and I can see it in the films now.

Brand Thumim worked as editor for Marc Karlin between 1980 and 1988 on the films For Memory, Nicaragua parts 2, 3 and 4, and Utopias.

BAMcinemaFest 2015 – Counting by Jem Cohen

“Counting” is Jem Cohen’s wandering tribute to the filmmaker Chris Marker, who died in 2012, and is structured as an essay-film told in 15 chapters of varying lengths. Cohen shot the footage during trips to Russia and Istanbul, and while walking around New York City, where he currently lives (many Brooklyn residents will see familiar landmarks, but Cohen’s camera-eye captures details that go unnoticed). Through his camera he constructs a personal travelogue that also acts as a map of the political climate of the last few years. But the energy of the film derives less from single images than the movement or flow of images. “Counting” reproduces the human experience of walking down the street, of wonder and concern and hope for the future.

via Whitechapel Gallery and Blouin Artinfo

Marc Karlin and Cinema Action 1968-1970

Promotional Material from Cinema Action’s Rocinante – found in the archive.

Last week in the BFI’s Essential Experiments slot, William Fowler presented the work of the filmmaking collective, Cinema Action. Two films were screen from the collective’s vast filmography – Squatters (1970), an attack on the Greater London Council regarding their lack of investment in housing . The film provided important – if controversial – information about the use of bailiffs in illegal eviction. And So That You Can Live (1981) which is widely recognised as one of Cinema Action’s finest works. The film follows the story of inspiring union convenor Shirley and the impact global economic changes have on her and her family’s life in rural South Wales. The landscape of the area, with all its complex history, is cross-cut with images of London, and original music from Robert Wyatt and Scritti Politti further reinforces the deeply searching, reflective tone. It was also broadcast on Channel 4’s opening night in November 1982.

Here is a history of Cinema Action via the BFI’s Screenonline

Cinema Action was among several left-wing film collectives formed in the late sixties. The group started in 1968 by exhibiting in factories a film about the French student riots of that year. These screenings attracted people interested in making film a part of political activism. With a handful of core members – Ann Guedes, Gustav (Schlacke) Lamche and Eduardo Guedes – the group pursued its collective methods of production and exhibition for nearly twenty-five years.

Cinema Action‘s work stands out from its contemporaries’ in its makers’ desire to co-operate closely with their working-class subjects. The early films campaigned in support of various protests close to Cinema Action‘s London base. Not a Penny on the Rent (1969), attacking proposed council rent increases, is an example of the group’s early style.

By the beginning of the seventies, Cinema Action began to receive grants from trades unions and the British Film Institute. This allowed it to produce, in particular, two longer films analysing key political and union actions of the time. People of Ireland! (1971) portrayed the establishment of Free Derry in Northern Ireland as a step towards a workers’ republic. UCS1 (1971) records the work-in at the Upper Clyde Shipyard; it is a unique document, as all other press and television were excluded.

Both these films typify Cinema Action‘s approach of letting those directly involved express themselves without commentary. They were designed to provide an analysis of struggles, which could encourage future action by other unions or political groups.

The establishment of Channel Four provided an important source of funding and a new outlet for Cinema Action. Films such as So That You Can Live (1981) and Rocking the Boat (1983) were consciously made for a wider national audience. In 1986, Cinema Action made its first fiction feature, Rocinante, starring John Hurt.

Marc Karlin joined Cinema Action in 1969. He had just returned to London after being caught up in the events of May ’68 in Paris while filming a US deserter. It was there where Karlin met Chris Marker, who was editing Cine-Tracts (1968) with Jean-Luc Godard at the time. Marker had just formed his film group SLON and had since released Far from Vietnam (1967), a collective cinematic protest with offerings from Jean-Luc Godard, Alain Resnais and Agnes Varda, inspired by the film-making practices of the Soviet film-maker, Alexander Medvedkin. The idea of taking this model of collective filmmaking back to the UK appealed greatly to Karlin, and was shared by many of his contemporaries. He details this enthusiasm in an interview with Sheila Rowbotham from 1998…

…when Marker started SLON, ideas about agitprop films were going around. Cinema Action had already started in England by 1969 when I joined. There was a relationship to the Russians: Vertov, the man with a movie camera, Medvedkin and his Russian agitprop train; the idea of celebrating life and revolution in film, and communicating that. Medvedkin had done that by train. SLON and Cinema Action both did it by car. Getting a projector, putting films in the boot, and off you went and showed films – which is what we did…

…when I joined there was no question of making documentaries for television. We showed our films at left meetings, where we would set up a screen, do leaflets and so on. It is often hilarious. I remember showing a film on housing in a big hall in the Bull Ring area of Birmingham. It started with machine gun noises, and Horace Cutler, the hated Tory head of the Greater London Council, being mowed down. The whole place just stopped and looked, but, of course, as soon as you got talking heads, people arguing or living their ordinary lives, doing their washing or whatever, we lost the audience. I learnt something through seeing that.

Evidently, Karlin was frustrated about the political and aesthetic approach of Cinema Action. In fact, salvaged in the archive is two thirds of a letter written by Karlin to Humphry Trevelyan that goes into some detail over the reasons for why Karlin intended to leave Cinema Action. For now, here is Karlin giving a somewhat exaggerated reason for leaving in the interview with Rowbotham…

…Schlacke (Cinema Action co-founder) had a thing about the materialist dialectic of film. Somehow or other – and I can’t tell you how are why – this meant in every eight frames that you had to have a cut. Schlaker justified this was some theoretical construct, but it made his films totally invisible. After a time I just got fed up. James Scott, Humphry Trevelyan and I started The Berwick Street Film Collective and later went on to join Lusia Films.

The Berwick Street Film Collective’s Nightcleaners (1975)

Find out more about the figures involved in Cinema Action and other British film collectives.

And…

Looking at Class. Film, Television and the Working Class in Britain, S, Rowbotham & H, Beynon, (Rivers Oram Press:2001)

Nicaragua Part 1 – Voyages – Channel 4 intro and outro – Eleventh Hour – 14 October 1985 – 10pm

Nicaragua Part 1: Voyages is available to download and stream.

Broadcast 14 October 1985 Channel 4 (ELEVENTH HOUR) (42 mins)

In 1978–79 American photographer Susan Meiselas documented the two insurrections that led to the overthrow of fifty years of dictatorship by the Somoza family in Nicaragua. Through an epistolary exchange over five unedited tracking shots across Meiselas’ photographs, the film articulates her relationship to the history she witnessed.

Advance Democracy! (1938) – extract | BFI National Archive

After a hard day’s work in London’s busy docks, Bert is encouraged by his wife May to listen to a wireless programme about the Co-operative Movement. He undergoes a rapid political transformation and exhorts his fellow dockworkers to join the annual May Day Parade. They spend a magnificent day at the parade – and the footage is overlaid with rousing music arranged by Benjamin Britten. The film’s director, Ralph Bond, co-founded the London Workers’ Film Society and believed in “putting the worker on the screen as a positive and vitally important aspect of life as a whole.” As well as the brilliantly filmed scenes of the men working in the dockyards, we see the struggle of May to put food on the table. This is in vivid contrast with the leisured, wealthy woman in this extract from the beginning of the film who telephones to order “Four nice soles, two plump chickens and a dozen meringues.”

via BFI

Visual Pleasure at 40: Laura Mulvey in discussion (Extract) | BFI

Academic-filmmaker Laura Mulvey discusses her groundbreaking essay ‘Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema’, published 40 years ago in 1975. Filmmakers Joanna Hogg and Isaac Julien join academics John David Rhodes, Tamar Garb, Mandy Merck and Emma Wilson to celebrate this “feminist manifesto”, a product of the politics of its time but one which remains an inspiration today.

The discussion was part of the BFI’s Cinema Reborn. Radical Film from the 70s season in April 2015.

On reaction from the conference please read Sophie Monks Kaufman’s The Timeless Pleasure of Laura Mulvey in Little White Lies, where she asks – can Laura Mulvey’s seminal feminist essay tell us anything new about gender politics in cinema?

And Benedict Morrison’s Galvanising the Humanities in The Oxonian Review.

Via BFI