Tagged: Marc Karlin

Memory And Illumination The Films of Marc Karlin – 30 OCT, King Juan Carlos I of Spain Center, NYU

Marc Karlin (1943-1999) is widely regarded as Britain’s most important but least known director of the last half century. His far-reaching essay films deal with working-class and feminist politics, international leftism, historical amnesia and the struggle for collective memory, about the difficulty but also the necessity of political idealism in a darkening world.

Chris Marker hailed him as a key filmmaker, and his work has inspired or been saluted by moving-image artists and historians such as Sally Potter, Sheila Rowbotham, John Akomfrah, Luke Fowler and The Otolith Group. Yet, in large part because his passionate, ideas-rich, formally adventurous films were made for television, until recently they were lost to history.

Memory And Illumination: The Films of Marc Karlin, the first US retrospective of his work, offers a broad survey of what the latest issue of Film Comment calls “the most daring docu-essays the public at large has yet to appreciate”. They include explorations of the emergent women’s liberation movement he made as part of his early membership of the Berwick Street Film Collective, his chronicles of the 1980s aftermath of the Nicaraguan Revolution, and his enduringly resonant meditations on post-1989 politics.

SCHEDULE:

FRIDAY 30 OCTOBER 2015

King Juan Carlos I of Spain Center, 53 Washington Square South

6:30pm: NICARAGUA: VOYAGES (1985)

Voyages is composed of stills by renowned Magnum photographer Susan Meiselas taken in 1978 and 1979 during the overthrow of the fifty-year dictatorship of the Somoza family. Written in the form of a letter from Meiselas to Karlin, it is a ruminative and often profound exploration of the ethics of witnessing, the responsibilities of war photography and the politics of the still image.

8pm: SCENES FOR A REVOLUTION (1991)

A film about aftermaths and reckonings. Revisiting material for his earlier four-part series (1985), Karlin returns to Nicaragua to examine the history of the Sandinista government, consider its achievements, and assess the prospects for democracy following its defeat in the general election of 1990. (Sponsored by King Juan Carlos I of Spain Center)

SATURDAY 31 OCTOBER 2015

Room 674, 721 Broadway (at Waverley Place)

12pm: THE SERPENT (dir. Marc Karlin, 1997), 40 min

The Serpent, loosely based on Milton’s Paradise Lost, is a blackly funny drama-documentary about media magnate and fanatical scourge of the Left Rupert Murdoch. A mild-mannered architect dreams of destroying this Dark Prince, but is assailed by his Voice of Reason which reminds him of the complicity of the liberal establishment in allowing Murdoch to dominate public discourse.

2pm: BETWEEN TIMES (dir. Marc Karlin, 1993), 50 min

Room 674, 721 Broadway (at Waverley Place)

A strikingly resonant work, not least in the wake of the recent re-election of the Conservative party in Britain, this is a probing and sometimes agonised essay – partially framed as a debate between socialism and postmodernism – about the paralysis of the Left and the need to locate new energies, spaces and forms of being that speak to emergent realities.

3:30pm: THE OUTRAGE (dir. Marc Karlin, 1995), 50 min

Room 674, 721 Broadway (at Waverley Place)

Echoes abound of Mike Dibb and John Berger’s Ways of Seeing (1972) in this hugely compelling film about Cy Twombly, about art, about television itself. According to director Steve Sprung it’s a film not about “the art of the marketplace, but the art that most of us leave behind somewhere in childhood, in the process of being socialized into the so-called world. The art which still yearns within us.”

5-6:30pm: Roundtable – TBA

7:30pm: FOR MEMORY (dir. Marc Karlin, 1986), 104 min

Room 674, 721 Broadway (at Waverley Place)

Beginning with a powerful interview with members of the British Army Film Unit who recall the images they recorded after the liberation of Belsen concentration camp, and conceived as an antidote to the wildly successful TV series Holocaust, For Memory is a multi-layered exploration – pensive and haunted – of cultural amnesia in the era of late capitalism that features historian E.P. Thompson, anti-fascist activist Charlie Goodman and Alzheimers patients.

SUNDAY 1 NOVEMBER 2015

Room 674, 721 Broadway (at Waverley Place)

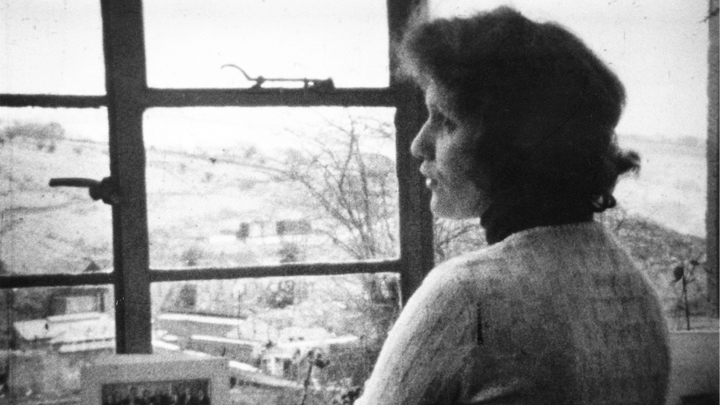

2pm: NIGHTCLEANERS (dir. Berwick Street Film Collective, 1975)

Made over three years by the Berwick Street Film Collective (Karlin, Mary Kelly, James Scott, Humphrey Trevelyan), Nightcleaners is a landmark documentary that follows the efforts of the women’s movement to unionize female night workers in London. It eschewed social realism and agit prop in favour of a ghostly, ambient and sonically complex fragmentage that elicited both hostile and ecstatic responses. Screen journal declared it the most “important political film to have been made in this country”, while Jump Cut claimed it was “redefining the struggle for revolutionary cinema”. (Sponsored by Gender and Sexuality Studies)

3:45pm: 36 TO 77 (dir. Berwick Street Film Collective, 1978)

Room 674, 721 Broadway (at Waverley Place)

Very rarely screened since its original release, this film was originally conceived as Nightcleaners Part 2. A portrait of Grenada-born Myrtle Wardally (b.1936), a leader of the Cleaners’ Action Group Strike in 1972, it features her discussing the partial success of that campaign and also her childhood in the Caribbean. It’s also an experiment – as probing as it is rapturous – in the politics of film form, and a fascinating deconstruction of the idea of Myrtle as a “symbol of struggle, the nightcleaners, working women, immigrants, mothers, blacks”.

MORE ON KARLIN:

Holly Aylett, Marc Karlin: Look Again (2015) http://liverpooluniversitypress.co.uk/products/60519

https://spiritofmarckarlin.com/

—–

Presented by the Colloquium for Unpopular Culture with the support of the Department of Cinema Studies, New York University

—–

QUERIES: ss162@nyu.edu

Close-ups on Revolution: the Nicaraguan Films of Marc Karlin, 30th Oct, organised by @autumnfarewells

Friday, October 30th 6:30pm

With SUSAN MEISELAS and HERMIONE HARRIS

VOYAGES (1985), 42 min.

SCENES FOR A REVOLUTION (1991), 110 min.

MARK KARLIN (1943-1999), one of the greatest British filmmakers of his generation, created an outstanding body of philosophically rich, formally bold work that explored themes of history, memory, labour, and political agency in a time of neoliberal despair.

Foremost among his achievements are the five films he made on the Nicaraguan revolution: spanning the Sandinista decade, focussing on rural and urban grassroots movements, attentive to the sadness and disappointments of the revolutionary process, they are a remarkable chronicle of a remarkable era.

MEMORY AND ILLUMINATION: THE FILMS OF MARC KARLIN, the first US retrospective of his work, begins with two works from this period. VOYAGES (1985) is composed of stills by renowned Magnum photographer SUSAN MEISELAS taken in 1978 and 1979 during the overthrow of the fifty-year dictatorship of the Somoza family. Written in the form of a letter from Meiselas to Karlin, it is a ruminative and often profound exploration of the ethics of witnessing, the responsibilities of war photography and the politics of the still image,

SCENES FOR A REVOLUTION (1991) is a film about aftermaths and reckonings. Revisiting material for his earlier 4-part series (1985), Karlin returns to Nicaragua to examine the history of the Sandinista government, consider its achievements, and assess the prospects for democracy following its defeat in the general election of 1990.

Post screening discussion with:

Susan Meiselas, Magnum photographer since 1980 and 1992 MacArthur Fellow.

Hermione Harris, Marc Karlin Archive.

Jonathan Buchsbaum, author of Cinema Sandinista: Filmmaking in Revolutionary Nicaragua, 1979-1990.

Susie Linfield, author of The Cruel Radiance: Photography and Political Violence.

—

Organized by Sukhdev Sandhu. QUERIES: ss162@nyu.edu

Presented by THE COLLOQUIUM FOR UNPOPULAR CULTURE and KING JUAN CARLOS I OF SPAIN CENTER.

Experimental filmmaker, Michael Snow – Channel 4 ‘Visions’. Broadcast 19 January 1983

Sharing the ‘documentary masters’ catagory at this year’s États généraux du film documentaire, Lussas, with Marc Karlin, was the experimental filmmaker, Michael Snow. Lussas curator, Federico Rossin, here introduces Snow.

Michael Snow (Toronto, 1929) is a major figure in contemporary art. His production is characterised by the close links binding works created using different types of media (film, photo, installation, painting, sculpture, music, writing). The modernity of Snow’s cinema pertains to his perception of the essential cinematic gesture, the camera movement, and the relations he explores between sound and image. His works have both a psychic and physical impact on the audience; they shake up the visible and plunge us into a profound experience of the perceptible. His films tend to be focussed on a cinematic strategy, on a process of film construction: yet they are never “minimalist”, making always sure that their forms can be apprehended by the spectator. They are rites of passage between pure perception and its representation, conceptual and extatic games playing with time and space, games that sometimes break the rules in order to put them in the spotlight.

Federico Rossin via États généraux du film documentaire – Lussas

For further viewing, here is an interview and profile of Michael Snow from 1983. It includes extracts from his films, ‘Back and Forth’, ‘Wavelength’, ‘La Region Central’, ‘So Is This’ and gallery piece ‘Two Sides To Every Story’.

The film was made for Channel 4 ‘Visions’ and broadcast 19 January 1983.

Interview: Simon Field; Director: Keith Griffiths

Thanks to Large Door.

Building Networks in a Contested Space: DMZ International Documentary Film Festival 2014

Here is a festival report from Ma Ran, reviewing the DMZ Documentary festival from September last year. Via Senses of Cinema

To visit the Korean Demilitarized Zone (DMZ) dividing North and South Korea might be a thrilling touristic option for Seoul’s visitors if they feel bored by the repetitive shopping and gourmet options in this vibrant Asian metropolis. Yet the DMZ as a buffer zone, evidence of division and Cold War remnant has also lent its symbolic weight to an emerging film festival – DMZ International Documentary Film Festival (DMZ Docs), launched in 2009. Taking Seoul subway line number three to its final stop, we find ourselves in the city of Goyang, which hosted all the DMZ Docs events this year, although the nearby city of Paju co-organised and co-funded the festival.

I want to approach DMZ Docs here as a “projective” film festival (to borrow a concept from Claire Bishop), based on a neo-liberal logic that foregrounds “projects” designed to foster connections, from three angles (1). Firstly, the idea suggests how we can think of film festivals as part of a series of arrangements made by the festival organisers in connecting with the urban setting and the national/regional cultural industries. Secondly, the idea also reinforces our understanding of film festivals as never isolated from global “networking,” both spatially and temporally. A network-based, projective film festival is capable of generating new visions and trends in both content and structure via programming and other events. Thirdly, a project-cantered logic is embodied in and through project markets and pitching sessions.

The relationship between a film festival and its hosting city is always intriguing in the Asian context. As the tenth largest city in Korea, Goyang impresses as a well-planned satellite city, with blocks of modern exhibition centres and shopping malls. Actually, the festival’s main multiplex theatre is located in a mall surrounded by sparse residential quarters and expansive undeveloped land. For sure, the entanglement and tension of the DMZ could be faintly sensed in this modern new town. But what was more strongly felt was Goyang and Paju’s joint official efforts to boost the local cultural industries via the film festival, especially given that Goyang aspires to become “a mecca for broadcasting and visual media in the northeast in the near future,” according to the vice chairman of the film festival Mr Choi, who is also the mayor of Goyang.

Indeed, DMZ Docs’ timing in late September is revealing about the interconnections and competitions between this festival and two other major documentary film festivals in East Asia – namely theTaiwan International Film Festival (TIDF, established 1998 and held annually held since 2014, this event takes place just after DMZ Docs in early October) and the Yamagata International Documentary Film Festival in Japan (YIDFF, established in 1989, this biennial event takes place in mid-October). Kicking off on September 17, DMZ Docs’ sixth edition boasted a line-up of 111 documentary films and three major competitive sections: the International Competition (twelve films), the Korean Competition (nine films) and Youth Competition (Korean short films by students), besides themed sidebars. Although the festival promoted a too generalized value of “peace, communication and life” in its booklet this year, its highly diversified programme incorporated some of the most exciting 2013-14 productions from around the world, to highlight refreshing methodologies, daring experiments and pressing issues in documentary cinema. It seemed as if the programmers were trying to bombard festivalgoers with as heterogeneous a selection as possible, in order to leave “what counts as a documentary” an open question.

At the same time, the retrospectives on Marc Karlin and Italian documentaries (from filmmakers such as Pier Paolo Pasolini and Cecilia Mangini) were simply too valuable to be ignored this year. The festival paid tribute to Karlin (1943-1999) in its “Masters” section, with a body of work that was introduced to the Asian world for the first time. The screenings also anticipated two major publications in the UK on this highly significant, yet little known British filmmaker.

Karlin carefully constructed his politically charged cinematic essays with hybridized materials from reenactments, found footage, interviews and even installations. Karlin’s filmmaking sets out to carve a space for what the director calls a “dream state,” full of the tension “between a world that is being illustrated and a world that is being illuminated” (2). While you might find in films such as Nightcleaners (Berwick Street Collection, 1975), For Memory (1982) and Utopias (1989) the Marker-esque traces of insightful contemplations and debates upon memory, history and the agency of people, we also notice that Karlin’s obsession with a cinema which reasons and thinks is also rooted in the sociohistorical undercurrents of his time. Instead of didactically addressing issues of class, gender, ideology and so forth, Karlin’s pursuit actually ventures into effectively engaging with the spectators via formal/structural experimentations.

In Nightcleaners, for example, Karlin and his colleagues approached the issue of unionizing underpaid women office cleaners in the 1970s by turning away from the conventions of observational documentary filmmaking of the time. That the film is a work being directed and constructed is revealed at the very beginning, as it “contains within itself a reflection of its own involvement in the history of the events being filmed” (3).

Even images of the interviewed subjects prove to be an unorthodox study of physiognomy, as the camera zooms in and out, adjusting its distance from the interviewee, while the spectators are confronted with partial facial expressions, movements of eyes and sometimes mismatching voice tracks which disrupt any authoritatively imposed meaning of the images. The filmmakers’ manipulation of images and sound therefore not only throw up questions about documentary truth and photographic images, it also positions the night cleaners’ fight and their campaign in a multi-layered, historically complex space in which tensions exist between the cleaners, the Cleaner’s Action Group and the unions.

DMZ Docs might be one of the contact points, no matter how limited the scope of reception, for spectators to trace the genealogy of global political filmmaking. Thus we may want to rethink the significance of a retrospective such as the one on Karlin. If films like Nightcleaners “could provide the basis for a new direction in British political filmmaking” in 1975 (festival catalogue), is a Karlin retrospective in 2014 simply about the rediscovery and redefinition of a lesser-known filmmaker vis-à-vis film history? Or could it also be a programming gesture of broader social significance? The retrospective may also offer documentary filmmakers and the like working with socially engaged methods and topics a certain framework of reference in speaking from a geopolitical perspective, as democracy protests and civil campaigns are renewed across East Asia in locales such as Okinawa, Seoul, Taipei, Hong Kong, and even some Mainland Chinese cities.

Read the rest of Ma Ran’s article here.

Senses of Cinema – Festival Report – Dec 2014 – Issue 73

Essay Film – Sheffield Doc/Fest 2015: John Akomfrah in Conversation

A seminal figure of activist and ‘engaged’ cinema, British filmmaker John Akomfrah has been leading the charge for over 30 years. As one of the founders of the Black Audio Film Collective, which sought to use documentary to explore questions of black identity in Britain, Akomfrah has continually pushed boundaries in both form and content. In this session he discussed his remarkable career with Francine Stock, the presenter of The Film Programme on BBC Radio 4. From Sheffield Doc/Fest 2015.

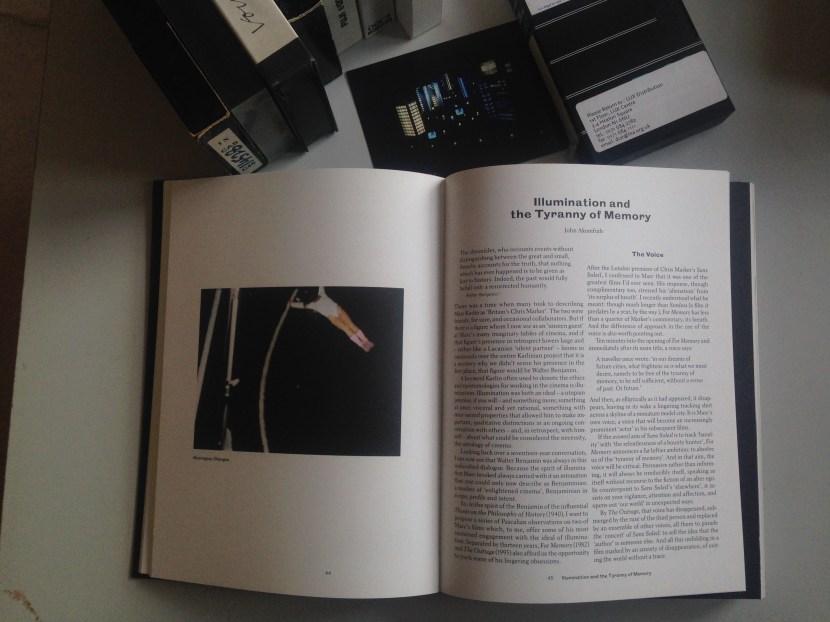

John Akomfrah’s essay on Marc Karlin, Illumination and the Tyranny of Memory, can be seen in Marc Karlin – Look Again, edited by Holly Aylett, published by Liverpool University Press. Available now at the BFI shop.

ARDECHE IMAGES – Les États généraux du film documentaire 17th-18th Aug 2015

Fragments of a filmmaker – Marc Karlin

Marc Karlin (1943-1999) belongs to that generation of filmmakers who, after having gone through the militant experience of the sixties and seventies, developed a new political filmmaking praxis in the eighties (the years of Margaret Thatcher and Ronald Reagan) by rethinking and moving beyond the Marxist tradition. His political activism expressed itself in a radical approach to documentary aesthetics and a constant attempt to build an alternative film culture in opposition to the media system – he was the editor and publisher of an independent film journal, Vertigo, founded in 1993. From Nightcleaners Part 1 (1972-75), made as a member of the Berwick Street Film Collective, Karlin saw the film form as a mirror of the revolutionary process: aesthetics had to be as radical as politics. All the rushes of the film, too similar to a classical agit-prop documentary, were completely deconstructed using the optical printer and the editing: the result was a complex avant-garde film about the contradictions of militant thinking and the women’s struggle for rights and union recognition. The discrepancies of militant cinema were inscribed directly in the film language and its materiality: this was the trademark of Karlin’s future work. In the eighties and nineties, Karlin made twelve films: he benefited from the new challenges and openings in television made possible by Channel 4 and he carved out a space that left uncompromised his political vision. The film form that Karlin thought about and refounded is the essay film: a hybrid form, open to political actuality (the revolution in Nicaragua for example), simultaneously turning to the past – considered as an archive of the oppressed – and towards the future – considered as a utopian promise. This hybrid form assembled elements from the archive (making visual metaphors and conceptual short circuit), arguments and quotations (a multi-layered literary voicing and a fragmented narrative), and an elegant visual choreography (camera tracking through space and time). At the beginning of the decade of the ascending neoliberalism, the age of oblivion, Karlin made For Memory (1982), an unorthodox portrait of capitalism, the growing of cultural amnesia and the tyranny of memory: the act of remembering is shown as an interrogation of the future and as a walk through the British revolutionary tradition – John Milton and the Levellers. Disappointed by the times he was living in Europe, Karlin, an internationalist socialist, was immediately interested in the Nicaragua revolution (that began in 1979 with the end of Somoza’s regime) and he decided to make a series of films about this challenging process. The starting point was a photobook made by Susan Meiselas: Voyages (1985) was the first of a four parts series that found a coda in 1991 with Scenes for a Revolution. Karlin never made a triumphant portrait of the country and never interviewed the main Sandinista leaders, as he wanted to be with the ordinary Nicaraguan people, filming from the roots and not from the top of the country. For each part of the project he invented and adjusted a dialectical film form in order to reveal all the daily beauty and the hard contradictions of the revolution. The five Nicaraguan films are not effective political or propaganda tools, nor ideological manifestos; they are subtle thinking forms about real struggle and real people. The following part of Karlin’s research about revolution was Utopias (1989), a melancholic and pensive essay about the crisis and the heritage of the left. Utopias was Karlin’s response to Margaret Thatcher’s claim that socialism was dead: the film is structured around an imaginary banquet where six guests, from different factions of the left are invited to debate the relevance of the socialist project for their own life’s work. If Utopias was about the past of the left, Between Times (1993) was a kind of a bitter coda made to imagine the future of the revolutionary tradition. After the collapse of the Soviet system and the birth of Tony Blair’s New Labour, Karlin was trying to make a film not about definitions, but an invitation to think about the possibility to find a place for the word “us” in the current political vocabulary and to build a possible resistance to barbarity. When Marc Karlin died, in 1999, The Independent wrote that he “was the most significant, unknown filmmaker working in Britain during the past three decades”: his work is now rediscovered, and we see it as an important missing figure in the documentary film history, the lost-and-found link between militant and experimental cinema.

By Federico Rossin

Partnered with the Marc Karlin Archive – Hermione Harris, Holly Aylett and Andy Robson.

Debates led by Federico Rossin – 17th-18th Aug 2105

See here for full schedule.

Marc Karlin on Karl-Marx-Allee – Cinemateca Nacional de Nicaragua – July 3 2015

In commemoration of the 36th anniversary of the Sandinista Revolution, the Nicaraguan Embassy in Germany arranged a Berlin screening of the documentary “La Construcción De Una Nación” (The Making of a Nation) (1985) director by Marc Karlin.

Ambassador Mrs. Karla Beteta Brenes, opened up the event which took place in Cafe Sibylle located in Berlin’s historic Karl-Marx-Allee. The cafe also acts as a museum to the street, displaying it’s turbulent history.

The documentary received great reception from the audience who highlighted the great work done by the director and the historical significance of the film.

The projection was made with the support of National Cinematheque of Nicaragua and forms part of the commemorative series organized by the embassy which takes place from July 3 to 10 and includes photography, poetry, documentary film and music.

This is one of many examples of the efforts in different countries to commemorate the 36th anniversary of the Sandinista Revolution.

via Cinemateca Nacional de Nicaragua

Marc Karlin’s Nicaragua – 36th Anniversary of the Sandinista Revolution – Amphitheatre Pedro Joaquin Chamorro – Cinemateca Nacional

Susan Meiselas – Nicaragua – Reframing History, 2004

In July 2004, for the 25th anniversary of the overthrow of Somoza, Susan Meiselas returned to Nicaragua with nineteen mural-sized images of her photographs from 1978-1979, collaborating with local communities to create sites for collective memory. The project, “Reframing History,” placed murals on public walls and in open spaces in the towns, at the sites where the photographs were originally made.

To see the film Meiselas made with Marc Karlin, containing her original Nicaragua photographs, please view Nicaragua Part 1: Voyages on Vimeo On Demand.

Broadcast 14 October 1985 Channel 4 (ELEVENTH HOUR) (42 mins)

In 1978–79 American photographer Susan Meiselas documented the two insurrections that led to the overthrow of fifty years of dictatorship by the Somoza family in Nicaragua. Through an epistolary exchange over five unedited tracking shots across Meiselas’ photographs, the film articulates her relationship to the history she witnessed.

Marc Karlin and Cinema Action 1968-1970

Promotional Material from Cinema Action’s Rocinante – found in the archive.

Last week in the BFI’s Essential Experiments slot, William Fowler presented the work of the filmmaking collective, Cinema Action. Two films were screen from the collective’s vast filmography – Squatters (1970), an attack on the Greater London Council regarding their lack of investment in housing . The film provided important – if controversial – information about the use of bailiffs in illegal eviction. And So That You Can Live (1981) which is widely recognised as one of Cinema Action’s finest works. The film follows the story of inspiring union convenor Shirley and the impact global economic changes have on her and her family’s life in rural South Wales. The landscape of the area, with all its complex history, is cross-cut with images of London, and original music from Robert Wyatt and Scritti Politti further reinforces the deeply searching, reflective tone. It was also broadcast on Channel 4’s opening night in November 1982.

Here is a history of Cinema Action via the BFI’s Screenonline

Cinema Action was among several left-wing film collectives formed in the late sixties. The group started in 1968 by exhibiting in factories a film about the French student riots of that year. These screenings attracted people interested in making film a part of political activism. With a handful of core members – Ann Guedes, Gustav (Schlacke) Lamche and Eduardo Guedes – the group pursued its collective methods of production and exhibition for nearly twenty-five years.

Cinema Action‘s work stands out from its contemporaries’ in its makers’ desire to co-operate closely with their working-class subjects. The early films campaigned in support of various protests close to Cinema Action‘s London base. Not a Penny on the Rent (1969), attacking proposed council rent increases, is an example of the group’s early style.

By the beginning of the seventies, Cinema Action began to receive grants from trades unions and the British Film Institute. This allowed it to produce, in particular, two longer films analysing key political and union actions of the time. People of Ireland! (1971) portrayed the establishment of Free Derry in Northern Ireland as a step towards a workers’ republic. UCS1 (1971) records the work-in at the Upper Clyde Shipyard; it is a unique document, as all other press and television were excluded.

Both these films typify Cinema Action‘s approach of letting those directly involved express themselves without commentary. They were designed to provide an analysis of struggles, which could encourage future action by other unions or political groups.

The establishment of Channel Four provided an important source of funding and a new outlet for Cinema Action. Films such as So That You Can Live (1981) and Rocking the Boat (1983) were consciously made for a wider national audience. In 1986, Cinema Action made its first fiction feature, Rocinante, starring John Hurt.

Marc Karlin joined Cinema Action in 1969. He had just returned to London after being caught up in the events of May ’68 in Paris while filming a US deserter. It was there where Karlin met Chris Marker, who was editing Cine-Tracts (1968) with Jean-Luc Godard at the time. Marker had just formed his film group SLON and had since released Far from Vietnam (1967), a collective cinematic protest with offerings from Jean-Luc Godard, Alain Resnais and Agnes Varda, inspired by the film-making practices of the Soviet film-maker, Alexander Medvedkin. The idea of taking this model of collective filmmaking back to the UK appealed greatly to Karlin, and was shared by many of his contemporaries. He details this enthusiasm in an interview with Sheila Rowbotham from 1998…

…when Marker started SLON, ideas about agitprop films were going around. Cinema Action had already started in England by 1969 when I joined. There was a relationship to the Russians: Vertov, the man with a movie camera, Medvedkin and his Russian agitprop train; the idea of celebrating life and revolution in film, and communicating that. Medvedkin had done that by train. SLON and Cinema Action both did it by car. Getting a projector, putting films in the boot, and off you went and showed films – which is what we did…

…when I joined there was no question of making documentaries for television. We showed our films at left meetings, where we would set up a screen, do leaflets and so on. It is often hilarious. I remember showing a film on housing in a big hall in the Bull Ring area of Birmingham. It started with machine gun noises, and Horace Cutler, the hated Tory head of the Greater London Council, being mowed down. The whole place just stopped and looked, but, of course, as soon as you got talking heads, people arguing or living their ordinary lives, doing their washing or whatever, we lost the audience. I learnt something through seeing that.

Evidently, Karlin was frustrated about the political and aesthetic approach of Cinema Action. In fact, salvaged in the archive is two thirds of a letter written by Karlin to Humphry Trevelyan that goes into some detail over the reasons for why Karlin intended to leave Cinema Action. For now, here is Karlin giving a somewhat exaggerated reason for leaving in the interview with Rowbotham…

…Schlacke (Cinema Action co-founder) had a thing about the materialist dialectic of film. Somehow or other – and I can’t tell you how are why – this meant in every eight frames that you had to have a cut. Schlaker justified this was some theoretical construct, but it made his films totally invisible. After a time I just got fed up. James Scott, Humphry Trevelyan and I started The Berwick Street Film Collective and later went on to join Lusia Films.

The Berwick Street Film Collective’s Nightcleaners (1975)

Find out more about the figures involved in Cinema Action and other British film collectives.

And…

Looking at Class. Film, Television and the Working Class in Britain, S, Rowbotham & H, Beynon, (Rivers Oram Press:2001)