Tagged: Marc Karlin

Nicaragua Part 1 – Voyages – Channel 4 intro and outro – Eleventh Hour – 14 October 1985 – 10pm

Nicaragua Part 1: Voyages is available to download and stream.

Broadcast 14 October 1985 Channel 4 (ELEVENTH HOUR) (42 mins)

In 1978–79 American photographer Susan Meiselas documented the two insurrections that led to the overthrow of fifty years of dictatorship by the Somoza family in Nicaragua. Through an epistolary exchange over five unedited tracking shots across Meiselas’ photographs, the film articulates her relationship to the history she witnessed.

Cinema Action – Steve Sprung – He Wanted to Make Movies the Way Everybody Else Does!

Tonight at the BFI, Southbank sees a celebration of the work of the film collective, Cinema Action. After a screening of Squatters (1970) and So That You Can Live (1981), Ann Guedes and Steve Sprung, Cinema Action members, will be present for a Q&A.

Steve Sprung was a key collaborator with Marc Karlin on five films and later contributed to the book Marc Karlin – Look Again.

Here is Steve’s article on Karlin from the summer of 1999. It featured in an issue of Vertigo magazine dedicated to Karlin, who died in the January of that year.

It’s hard to imagine it, the idea of Marc turning in his grave, but surely he must have. May Day… Saturday the first, not Bank Holiday Monday.

Nothing to do with his beloved Arsenal, but with that other, mostly negative, mover of his being, television. In a programme hosted by Jon Snow the British people were allegedly invited to make a late but vitriolic judgement on Margaret Thatcher’s seventeen years in government.

I imagined the rage it would have elicited from Marc – not against the obvious target, Thatcher and her die-hard crew – but against all those claiming it was Maggie who done it, that this she-devil incarnate must now take all the blame. At a time when cleansing, by all manner of powers over other powers, dominates our television screens, this was an equally crude wiping clean. Television’s refusal to engage with the complex process of those years – years which constitute a substantial chunk of our adult lives as well as moulding future generations – would have had him livid.

It was this Thatcher period which formed the context for my work with and for Marc. My background had been in a more agitational cinema, but I had been struggling for years, labouring away in the basement under Lusia Films, with a film about a failed strike under the previous Labour government, and its role in laying the ground for the Thatcherism that was to come. How to talk about events which had been mischaracterised both by the dominant media industry and by the working classes’ own trade union and political organisations? How to reveal this massive content, tell this necessary story, and find an adequate form in which to do it?

This film, The Year of the Beaver, finally emerged in the early eighties. It manages to create multiple layers of meaning, drawing connections between the myriad things it had been necessary to take on board. When he saw it, Marc hugged me. This, I felt, was our first real meeting. On looking again at Marc’s early films, I came to realise they had always been about looking beneath the surface to reveal connections. In a sense they are films which try to open up for the viewer the process we went through as filmmakers, inviting them, as far as was possible, to share the journey we had made. Thus they were films which interrogated their audiences as much as they interrogated their subject-matter, just as we had interrogated ourselves as part of their making.

I worked on five films with Marc. I was one of many with whom he talked at great length about the ideas underpinning each new project. We would try out sequences with video-cameras, and these I would cut and re-cut, often summoned to Lusia by a Saturday morning ’phone call.

I chose not to attend the actual shoots (on 16mm) so that I could come to the rushes with as fresh an eye as possible. It was as if the material had been encircled, caught by the camera. Now the ideas, and the film which would bear them, had to be re-discovered, and brought to life on the editing table.

The Outrage, 1995

Marc, insecure as he was, as we all are when laying ourselves on the line and taking risks to say more than we readily know how to say, was incredibly secure in terms of entrusting me with the material. When viewing my cuts, he had the sharpest eye for detail, and its relationship to the whole, but he gave me unhindered space in which to work. He never demanded that this or that shot must be used, and was in this sense able to subsume his ego to the film.

Why?

Because the films were about something bigger than Marc or any of us who worked on them, and we were simply engrossed in trying to understand how to bring the ideas to life.

Paradoxically perhaps, the first film I edited with Marc was the last of his more conventionally “political” and “documentary” works.

Between Times was a journey through the countervailing political ideas of the “in between times” he felt we were in, and through the sort of questions Marc felt this period posed for anyone still concerned with bringing about revolutionary change. I’ll always remember the end of the film: the two protagonists, who’d been conducting an argument by presenting various documentary stories, were revealed to be one single, contradiction-filled person. But this was a person who held on to a simple truth: when we had none of the technology to construct a new world we had the capacity to dream it; now that we had the technology, we seemed to have lost the capacity to dream the dream.

Between Times was a turning point in his and our filmmaking. Marc moved towards the politics of culture and away from films whose legitimacy derived from concrete documentary material based on ongoing political action. He went for a new type of direct cinema, looking at how the world is culturally constructed and by whom, and exploring the blockages preventing perceptions of the world which are different from those of the more dominant vision.

The Outrage, 1995

This required a different use of the material basic to documentary filmmaking, an approach which freed itself from following the sequence of particular events or political actions. It was an approach I had begun to explore in a film I had recently co-directed, Men’s Madness, and something which Marc’s practice, and his work with people such as Chris Marker, had enabled him to appreciate. He saw it as a step forward in opening up the political space of cinema, and he continued to develop it further in his films, drawing increasingly on fictional and scripted elements.

In The Outrage, a man goes in search of a painting, or, rather in search of the art in himself. This film shows another aspect of Marc’s work: the supposed subject of the film – in this case a portrait of the artist Cy Twombly – is turned upside down and viewed from an unexpected angle. Thus we are able to look at the subject afresh, to look at art and painting from the point of view of the viewer. We go through precisely the process of re-discovery Marc had gone through to be able to create the film. This journey we, his collaborators, had also shared, leading us to engage with that essential need which emerges as art. Not the art of the market place, but the art that most of us leave behind somewhere in childhood, in the process of being socialised into the so-called real world. The art which still yearns within us.

The Outrage contained an important sequence which talked about the role of advertising (and this includes MTV) in our visual culture. This is the one place where it is permitted for images to be freely given over to the imagination. But here imagination has become no more than a commodity, and the images bear the emptiness of this prostitution. In contrast, the richness of The Outrage’s visual imagery and the imaginativeness of its narrative form are inseparable from an equally rich and meaningful content. The film’s imagery does not flow over and mesmerise the viewer; it asks for a more complete involvement.

Marc’s next film, The Serpent, about the demonising of Rupert Murdoch, continued this rich texturing of image, sound and meanings. I’m sure Marc had experienced visions of Murdoch horned and spitting fire, but he wanted to interrogate that whole process of “demonising” which we all revel in. He wanted, crucially, to look at what it really avoids, to address the difficult political questions it allows us to duck; how to fight against a culture which apparently offers more of everything, more channels, more choices, more democracy, more freedom? and how to ask another simple, yet largely unasked, question – where are all these choices leading? Freedom to do what?

It was during the making of The Serpent that Marc introduced Milton to me and to his films, in the epic form of Paradise Lost. This poem had obsessed him for some considerable time. It speaks of the devil not from a moral perch, nor of him as a foreigner, but as being resident somewhere in all of us. It was more than the text, however, that was rhyming with us. Just as Milton became isolated in his lifetime through his constant search for illumination, labouring to understand why the revolution of his time had failed, so we too were destined to a similar isolation. We had made ourselves outsiders by virtue of our way of working, by the endeavour of Marc’s kind of filmmaking. Perhaps this was the only place we could be. We required an audience who wished to make a journey similar to ours, whereas we live in a society in apparent need of constant triviality, one afraid to take itself too seriously for fear of what it might uncover, and desirous of seemingly “entertaining itself to death”. Perhaps this is the message of Murdoch’s easy victory.

The Outrage, 1995

This experience of being outside, witnessing a culture whose memory is in a dangerous state of decay, provided the impetus for The Haircut (a short about the cultural conformity of New Labour) and for Marc’s last work in progress on Milton: A Man who Read Paradise Lost Once Too Often.

Marc was preparing to keep up the fight. Coming from a different space, I had my reservations. The references that resonated for him were different from mine. I also knew he was engaged in a holding operation, perhaps one which few would be able to understand.

The film was not to be.

I can remember a sense amongst many of us present in the pub after Marc’s funeral of this being the end of an era. Would there be space in future for his kind of work? Where would it find its funding?

It seems to me there is an equally important question before us: will we be able, as time goes by, even to conceive of such work? It requires a skill that can only be developed through practice, and a great deal of time – gestation time and, especially, post-production time.

Marc’s are films about a process, and thus they have an organic life to them. They were not made with an eye to filling a television slot, but were designed to take the time they needed to take to communicate the exploration they had undertaken. This is why their significance lingers on beyond the momentary blip they represented in the continuous present that is television, and why they will outlive their own time. They are representations of the complex processes by means of which we come to understand who we are, where we are and what we are.

Steve Sprung is a film director and editor.

Vertigo Volume 1 | Issue 9 | Summer 1999

If I Had Four Dromedaries – ‘Si j’avais quatre dromadaires’ (1966) Chris Marker

Chris Marker’s If I Had Four Dromedaries (1966).

Composed entirely of still photographs shot by Marker himself over the course of his restless travel through twenty-six countries, If I Had Four Dromedaries stages a probing, at times agitated, search for the meanings of the photographic image, in the form of an extended voice-over conversation and debate between the “amateur photographer” credited with the images and two of his colleagues. Anticipating later writings by Roland Barthes and Susan Sontag (who professed her admiration for the film) If I Had Four Dromedaries reveals Marker’s instinctual understanding of the secret rapport between still and moving image.

Clearly, If I Had Four Dromedaries, was a key influence on Marc Karlin’s Nicaragua Part 1: Voyages.

The first part in Marc Karlin’s extraordinary Nicaraguan series, comprises of stills by the American photographer Susan Meiselas. Between 1978 and 1979, Meiselas captured the two revolutionary insurrections which brought the FSLN to power in Nicaragua, overthrowing the fifty year dictatorship of the Somoza family. The film is in the form of a letter, written by Meiselas to Karlin. Through her own words, the film interrogates the responsibility of the war photographer, the line between observer and participant, and the political significance of the photographic image.

Thanks to ChrisMarker.org

Look Again #3 – Sally Potter

Sally Potter writes a beautiful, heartfelt foreword in Marc Karlin – Look Again, describing Marc Karlin as a cinematic pioneer, thinker and activist. She also goes on to recall her first meeting with Karlin, after a screening of Nightcleaners, and how he kindly shared the Berwick Film Street Collective’s facilities while she was making her film, Thriller in 1979.

Here is an interview between Sally Potter and Wendy Toye, broadcast on Channel 4 on 9th May 1984. It was commissioned for the film programme, Visions (1983-1986). John Ellis, who co-produced the programme via his company Large Door, has very recently uploaded a collection of complete episodes from the series. ‘So there is now a Large Door channel for our moribund independent production company, with a selection from the hundred or so programmes we produced’.

Two women directors of different generations – both trained as dancers – meet for the first time. Sally Potter’s first feature ‘Gold Diggers’ had just been released. Wendy Toye’s career began in theatre and she directed her first short ‘The Stranger left No Card’ in 1952. She worked for Korda and Rank, making both comedies and uncanny tales. Directed by Gina Newson for Channel 4’s Visions series, 1984.

Large Door was set up in 1982 to produce Visions, a magazine series for the new Channel 4. Initially there were three producers, Simon Hartog and Keith Griffiths and John Ellis. Visions continued until 1986, producing 36 programmes in a variety of formats. Hartog and Ellis continued producing through the company, broadening out from cinema programmes to cover many aspects of popular culture from food to television.

Visions was a constantly innovative series, and John Ellis’ article in Screen Nov-Dec 1983 about the first series gives a flavour of its range:

Especially during the earlier months of production, we vacillated between two distinct conceptions of the programme: one, the more conventional, to use TV to look at cinema; the other, more avant-gardist, to treat the programmes as the irruption of cinema into TV. […]

We found that virtually all of our programme items could be categorised into four headings:

1) The Report, a journalistic piece reflecting a particular recent event: a film festival like Nantes or Cannes, the trade convention of the Cannon Classics group.

2) The Survey of a particular context of film-making, like the reports from Shanghai and Hong Kong, and the critical profile of Bombay popular cinema.

3) The Auteur Profile, like the interviews with Michael Snow and Paul Schrader, Chris Petit’s hommage to Wim Wenders, or Ian Christie’s interviews with various people about their impressions of Godard’s work.

4) The Review, usually of a single film, sometimes by a literary intellectual, ranging from Farrukh Dhondy on Gandhi to Angela Carter on The Draughtsman’s Contract. About half the reviews were by established film writers, like Colin McArthur on Local Hero or Jane Clarke on A Question of Silence.

The third series of Visions, a monthly magazine from October 1984 added further elements. Clips was a review of the month’s releases made by a filmmaker or journalist (eg. Peter Wollen, Neil Jordan, Sally Potter) consisting entirely of a montage of extracts with voice-over. We introduced the idea of the filmmaker’s essay, borrowed from the French series Cinema, Cinemas, commissioning Chantal Akerman and Marc Karlin to do what they wanted within a limited budget and length. The plan to commission Jean-Luc Godard fell in the face of his insistence on 100% cash in advance with no agreed delivery date. And then there was no further commission.

Further Reading and Viewing

http://cstonline.tv/resurrected-visions-on-youtube-the-large-door-channel

https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCkw6_1SR89FKzlV50e0aWAQ

https://vimeo.com/user12847153

http://www.screenonline.org.uk/people/id/490062/

Charlotte Crofts (2003) Anagrams of Desire: Angela Carter’s Writings for Radio, Film and Television(London: Chatto & Windus), pp. 168–193

John Ellis Channel 4: Working Notes, Screen, November-December 1983 pp.37-51

John Ellis Censorship at the Edges of TV – Visions, Screen, March-April 1986 pp.70-74

John Ellis Broadcasting and the State: Britain and the Experience of Channel 4, Screen, May-August 1986 pp.6-23

John Ellis Visions: a Channel 4 Experiment 1982-5 in Experimental British Television, ed Laura Mulvey, Jamie Sexton, University of Manchester Press 2007 pp.136-145

John Ellis What Did Channel 4 Do For Us? Reassessing the Early Years in Screen vol.49 n.3 2008 pp.331-342

BOOK LAUNCH! Marc Karlin – Look Again, BFI Southbank 30th April 2015

The Marc Karlin Archive is please to announce Marc Karlin – Look Again, edited by Holly Aylett, published by Liverpool University Press, is on sale now!

So please come and celebrate with us at our book launch at BFI Southbank on Thursday 30th April, courtesy of Liverpool University Press and the British Film Institute.

The launch will follow on from an Essential Experiments screening of Between Times (50′), curated by William Fowler, in NFT3, April 30th at 6.15pm, with a panel discussion led by Gareth Evans with Holly

Aylett, Sophie Mayer, Steve Sprung, and John Wyver.

There will then be a foyer break with wine on the house and books available.

At 8.40pm there will be a further double bill with The Outrage (50′) and The Serpent (40′). See the link below to book! If you are interested in attending both screenings, then please call the BFI box office to purchase a joint ticket – 020 7928 3232 – 11.30am to 20.30pm daily.

Hope to see you there!

Marc Karlin – Look Again, edited by Holly Aylett, published by Liverpool University Press

Look Again #1 – Marsha Marshall

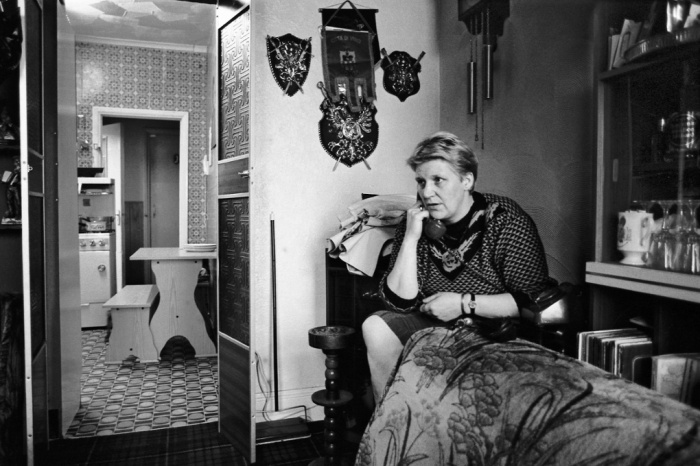

In the lead-up to the release of Marc Karlin-Look Again here are a collection of portraits focusing on the people Karlin documented in his films. Up first is Marsha Marshall, secretary of the Women Against Pit Closures (Barnsley Group) during the 1984-85 Miners’ Strike.

Marsha Marshall circa 1986 ©The Marc Karlin Archive

Marsha Marshall, who died in April 2009, lived with her miner husband, Stuart ‘Spud’ Marshall, in Wombwell, near Barnsley at the time of the 1984/84 Miners Strike. Spud was one of the first to be arrested during the dispute on a picket line in Nottinghamshire. This event politicised Marsha, and soon with others she founded the Women’s Against Pit Closures. Having never been abroad before, her duties as secretary of the WAPC, took her to France, Italy, Bulgaria, and the USSR – and in Rome she spoke at a rally to over 4,000 Italian trade unionists.

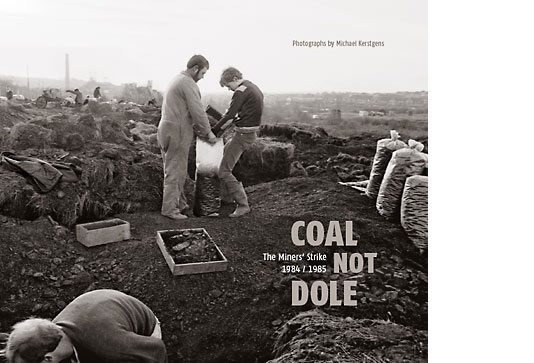

Marsha is featured in Michael Kerstgens’ photographic collection, Coal Not Dole, The Miner’s Strike 1984/85 published by Peperoni Books. In 1984, Michael Kerstgens was a young German photography student who decided to travel to Britain and document the dispute. People were wary of him, as an outsider, and so he was limited to photographing events on the periphery.

However, things changed when he met the activist Stuart “Spud” Marshall. Spud trusted him immediately and opened the door for Kerstgens to photograph not only the heat of the action but also more intimate moments beyond the picketing, violent clashes with the police, and public discussions on the political stage. Kerstgens photographed soup kitchens, meetings behind closed doors, and the wives of striking miners, including Marsha.

Marsha Marshall supports picketing miners with a donation of cigarettes. © Michael Kerstgens

Marsha Marshall on the telephone to Vanessa Redgrave, Wombwell, 1985, © Michael Kerstgens

Around 1986, Karlin interviewed Marsha Marshall for his film ‘Utopias’ – a film about socialism in Britain, broadcast on Channel 4 in 1989. Marsha would be one of the socialist voices in his film. Karlin, here, recalls his creative intentions,

I was filming Utopias in 1986, around the time Margaret Thatcher said she aimed to destroy socialism once and for all. I was determined to say otherwise, obviously. I wanted to do portraits of different socialism, take ideas about it and so on, but to put them all on one boat. Utopias was like a banquet table. I liked the idea of having somewhere all these people could be together, where David Widgery, Sheila Rowbotham and Jack Jones, Sivanandan, Bob Rowthorn, and the miner’s wife, Marsha Marshall, were all going to be there. All these visions of socialism were great. I am totally naïve, but I shall remain to the end, so I just wanted them all at the table. Can you imagine? No: But the film did.

Marc Karlin and Marsha Marshall, circa 1986, ©The Marc Karlin Archive

This is an edited extract of Marsha’s chapter from ‘Utopias’. In this section she recalls the miners’ strike and speaks about her fears for the future of her community.

‘Spud’ Marshall at home in Kendray Barnsley, September 2012 © Michael Kerstgens

Further Reading –

Coal Not Dole, The Miners’ Strike 1984/1985, by Michael Kerstgens, is published by Peperoni Books

http://peperoni-books.de/coal_not_dole00.html

http://www.southyorkshiretimes.co.uk/news/local/strike-hero-marsha-dies-at-64-1-615649

Looking at Class. Film, Television and the Working Class in Britain, S, Rowbotham & H, Beynon, (Rivers Oram Press: 2001)

BFI – Essential Experiments – Marc Karlin, April 30, 2015. NFT3

Marc Karlin – Look Again. The Print Run

Designer, Roland Brauchli, recently traveled to Barcelona to sign off and supervise the printing of Marc Karlin – Look Again. Here are some behind the scene glimpses of the printing process.

What will become Marc Karlin – Look Again.

Some of the pages cut to size.

Marc Karlin – Look Again. First Edition. Edited by Holly Aylett. Liverpool University Press.

Pre-order now – Release 31 March 2015

http://shop.bfi.org.uk/pre-order-marc-karlin-look-again.html#.VQLvIinVt0s

https://global.oup.com/academic/product/marc-karlin-9781781381656?cc=gb&lang=en&

http://www.amazon.co.uk/Marc-Karlin-Again-Holly-Aylett/dp/1781381658

BFI – Essential Experiments – The Outrage + The Serpent, April 30, 2015. 8.40PM NFT3

Two unusual documentaries; one inspired by the paintings of Cy Twombly, and one an interesting portrayal of Rupert Murdoch.

1995 BBC2

Directed by Marc Karlin

50 min

The tactile, abstract canvases of celebrated painter Cy Twombly form the focal point of this unusual artist documentary. The fictional, mysterious M does the looking; reacting initially with rage and frustration, before asking why. Karlin reflects on our changing relationship to art while also considering its significance in our lives, revealing himself in the process. This is an inspiring example of how to challenge the formal, conventional limits of film and TV.

The Serpent

1997 Ch4

Directed by Marc Karlin

40 min

This decidedly bold drama-documentary sees Rupert Murdoch re-imagined as the Dark Prince from Milton’s Paradise Lost. Commuter Michael Deakin drifts off to sleep and dreams of destroying the Prince who has made England ‘a hard, sniggering, resentful, hard shoulder of a place.’ But the voice of reason has other plans, and Deakin himself is implicated in the Prince’s rise to power.

Joint ticket available for Essential Experiments £16, concs £12.50 (Members pay £1.70 less)

BFI – Essential Experiments – Between Times + discussion Apr 30, 2015 6:15 PM NFT3

1993 Ch4

Directed by Marc Karlin

50 min

Self-reflection, collaboration and debate were vital to Karlin, who was a member of the Berwick Street Collective and a key figure in the political avant-garde from the 1970s onwards. To launch new book Marc Karlin: Look Again, we present his insightful, far-reaching TV piece about the state of the Left after Thatcher. Join us as we also discuss with his friends and collaborators the work and legacy of this much-missed radical.

Joint ticket available for Essential Experiments £16, concs £12.50 (Members pay £1.70 less)