Tagged: Chris Marker

Marc Karlin and Cinema Action 1968-1970

Promotional Material from Cinema Action’s Rocinante – found in the archive.

Last week in the BFI’s Essential Experiments slot, William Fowler presented the work of the filmmaking collective, Cinema Action. Two films were screen from the collective’s vast filmography – Squatters (1970), an attack on the Greater London Council regarding their lack of investment in housing . The film provided important – if controversial – information about the use of bailiffs in illegal eviction. And So That You Can Live (1981) which is widely recognised as one of Cinema Action’s finest works. The film follows the story of inspiring union convenor Shirley and the impact global economic changes have on her and her family’s life in rural South Wales. The landscape of the area, with all its complex history, is cross-cut with images of London, and original music from Robert Wyatt and Scritti Politti further reinforces the deeply searching, reflective tone. It was also broadcast on Channel 4’s opening night in November 1982.

Here is a history of Cinema Action via the BFI’s Screenonline

Cinema Action was among several left-wing film collectives formed in the late sixties. The group started in 1968 by exhibiting in factories a film about the French student riots of that year. These screenings attracted people interested in making film a part of political activism. With a handful of core members – Ann Guedes, Gustav (Schlacke) Lamche and Eduardo Guedes – the group pursued its collective methods of production and exhibition for nearly twenty-five years.

Cinema Action‘s work stands out from its contemporaries’ in its makers’ desire to co-operate closely with their working-class subjects. The early films campaigned in support of various protests close to Cinema Action‘s London base. Not a Penny on the Rent (1969), attacking proposed council rent increases, is an example of the group’s early style.

By the beginning of the seventies, Cinema Action began to receive grants from trades unions and the British Film Institute. This allowed it to produce, in particular, two longer films analysing key political and union actions of the time. People of Ireland! (1971) portrayed the establishment of Free Derry in Northern Ireland as a step towards a workers’ republic. UCS1 (1971) records the work-in at the Upper Clyde Shipyard; it is a unique document, as all other press and television were excluded.

Both these films typify Cinema Action‘s approach of letting those directly involved express themselves without commentary. They were designed to provide an analysis of struggles, which could encourage future action by other unions or political groups.

The establishment of Channel Four provided an important source of funding and a new outlet for Cinema Action. Films such as So That You Can Live (1981) and Rocking the Boat (1983) were consciously made for a wider national audience. In 1986, Cinema Action made its first fiction feature, Rocinante, starring John Hurt.

Marc Karlin joined Cinema Action in 1969. He had just returned to London after being caught up in the events of May ’68 in Paris while filming a US deserter. It was there where Karlin met Chris Marker, who was editing Cine-Tracts (1968) with Jean-Luc Godard at the time. Marker had just formed his film group SLON and had since released Far from Vietnam (1967), a collective cinematic protest with offerings from Jean-Luc Godard, Alain Resnais and Agnes Varda, inspired by the film-making practices of the Soviet film-maker, Alexander Medvedkin. The idea of taking this model of collective filmmaking back to the UK appealed greatly to Karlin, and was shared by many of his contemporaries. He details this enthusiasm in an interview with Sheila Rowbotham from 1998…

…when Marker started SLON, ideas about agitprop films were going around. Cinema Action had already started in England by 1969 when I joined. There was a relationship to the Russians: Vertov, the man with a movie camera, Medvedkin and his Russian agitprop train; the idea of celebrating life and revolution in film, and communicating that. Medvedkin had done that by train. SLON and Cinema Action both did it by car. Getting a projector, putting films in the boot, and off you went and showed films – which is what we did…

…when I joined there was no question of making documentaries for television. We showed our films at left meetings, where we would set up a screen, do leaflets and so on. It is often hilarious. I remember showing a film on housing in a big hall in the Bull Ring area of Birmingham. It started with machine gun noises, and Horace Cutler, the hated Tory head of the Greater London Council, being mowed down. The whole place just stopped and looked, but, of course, as soon as you got talking heads, people arguing or living their ordinary lives, doing their washing or whatever, we lost the audience. I learnt something through seeing that.

Evidently, Karlin was frustrated about the political and aesthetic approach of Cinema Action. In fact, salvaged in the archive is two thirds of a letter written by Karlin to Humphry Trevelyan that goes into some detail over the reasons for why Karlin intended to leave Cinema Action. For now, here is Karlin giving a somewhat exaggerated reason for leaving in the interview with Rowbotham…

…Schlacke (Cinema Action co-founder) had a thing about the materialist dialectic of film. Somehow or other – and I can’t tell you how are why – this meant in every eight frames that you had to have a cut. Schlaker justified this was some theoretical construct, but it made his films totally invisible. After a time I just got fed up. James Scott, Humphry Trevelyan and I started The Berwick Street Film Collective and later went on to join Lusia Films.

The Berwick Street Film Collective’s Nightcleaners (1975)

Find out more about the figures involved in Cinema Action and other British film collectives.

And…

Looking at Class. Film, Television and the Working Class in Britain, S, Rowbotham & H, Beynon, (Rivers Oram Press:2001)

If I Had Four Dromedaries – ‘Si j’avais quatre dromadaires’ (1966) Chris Marker

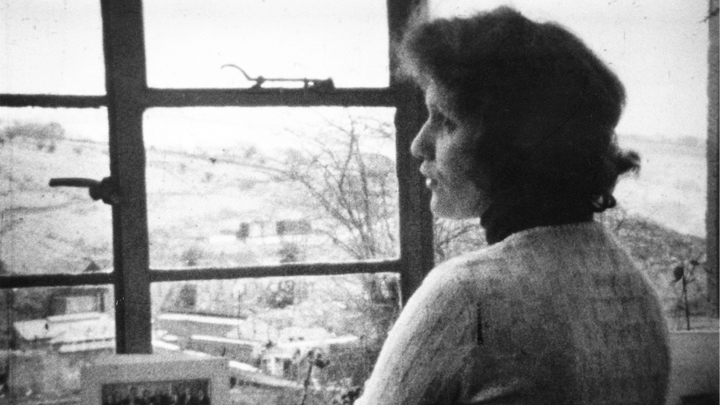

Chris Marker’s If I Had Four Dromedaries (1966).

Composed entirely of still photographs shot by Marker himself over the course of his restless travel through twenty-six countries, If I Had Four Dromedaries stages a probing, at times agitated, search for the meanings of the photographic image, in the form of an extended voice-over conversation and debate between the “amateur photographer” credited with the images and two of his colleagues. Anticipating later writings by Roland Barthes and Susan Sontag (who professed her admiration for the film) If I Had Four Dromedaries reveals Marker’s instinctual understanding of the secret rapport between still and moving image.

Clearly, If I Had Four Dromedaries, was a key influence on Marc Karlin’s Nicaragua Part 1: Voyages.

The first part in Marc Karlin’s extraordinary Nicaraguan series, comprises of stills by the American photographer Susan Meiselas. Between 1978 and 1979, Meiselas captured the two revolutionary insurrections which brought the FSLN to power in Nicaragua, overthrowing the fifty year dictatorship of the Somoza family. The film is in the form of a letter, written by Meiselas to Karlin. Through her own words, the film interrogates the responsibility of the war photographer, the line between observer and participant, and the political significance of the photographic image.

Thanks to ChrisMarker.org

550 boxes – Chris Marker’s Collection – Cinémathèque française

The Cinémathèque française have just released an update on their recent acquisition of Chris Marker’s archive. Thanks to ChrisMarker.org for translation.

In the Spring of 2013, the Cinémathèque française took possession to its archives 550 large moving boxes containing the archives of Chris Marker, deceased during the summer of the preceding year. Under the conduct of a scientific committee of individuals close to the filmmaker and familiar with his work, the inventory of the estate began rapidly. The total duration of the operation was estimated at around three years. So where are we, two years later?

The 550 boxes that make up the estate are divided as follows:

5 boxes of posters; 6 boxes of LP records and musical documents; 15 boxes of photographs; 55 boxes of objects, miniatures…; 66 boxes of audiovisual material (Beta, master…); 98 boxes of archives (press documentation, files & folders); 112 boxes of VHS and DVD edits and personal recordings; 137 boxes of periodicals and books.

At this point in time, the boxes of photographs have been thoroughly inventoried, although not all photographs have been identified. Similarly, the inventory of ‘apparatuses/apparatii’ [appareils] is complete. The library of Chris Marker, rich with some 137 boxes, has been made the object of a deeper study and is approaching completion. An actively used library, as opposed to a collector’s library, it presents a singularity in so far as each work is stuffed with diverse documents: letters, press clipings, etc. Each volume therefore has been the object of a precise description of the elements that it contains. To get an idea of this library, the inventory would be certainly instructive, but evidently insufficient. A virtual library project is therefore being considered.

The inventory continues currently with the objects, posters, audiovisual materials and paper archives. This work should be completed by Fall 2015. The inventory of hard drives, on which Marker worked during the course of the last 20 years of his life, has also begun. These discs contain several million files. To bring to fruition the description of their contents will be a long-term work [‘de longue haleine’, literally ‘of long breath’]. Similarly, initial work on the state of more than a thousand digital diskettes [floppies/zip/flash drives presumably] has begun with the help of a digital conservation specialist [digital archivist]. A work of securing and restoring, an indispensible prior step to taking an inventory, will be conducted in the coming months.

During the course of the Fall, the VHS, DVD, CD and vinyl LPs will be inventoried, permitting thereby, with the horizon of Summer 2016, to have analyzed the sum total of the boxes of the estate and to have arrived at an initial, global view of its coherence and richness. Work on cataloging can then begin, with the objective remaining to place the estate at the disposition of researchers starting in 2018, while presenting it as well in the form of a grand exhibition at the Cinémathèque française. The scientific committee is already working toward this goal.

via chrismarker.org

Icarus Films Presents: On Strike!: Chris Marker and The Medvedkin Group

In 1967, Chris Marker and Mario Marret filmed BE SEEING YOU (À BIENTÔT J’ESPÈRE), about a strike and factory occupation-the first in France since 1936-by textile workers in the city of Besancon, the goals of which were unusual because the workers refused to disassociate their salary and job security demands from a social and cultural agenda.

Nevertheless when the film was completed, and the filmmakers returned to screen it for the workers in Besancon, many of them were not happy with it. LA CHARNIERE, the audio recording of their intense debate after the screening, is included on this disc as an extra, accompanied by photographs of the film workshops, shot by Ethel Blum.

In response Marker and his colleagues reorganized their efforts, and began training workers to collaboratively make their own films, under the name “The Medvedkin Group”, after Alexander Medvedkin, who invented the cine-train, a mobile production unit that toured the USSR in 1932 filming workers and farmers. CLASS OF STRUGGLE, their first film, picks up a year later and focuses on the organizing efforts of workers at a nearby watch factory, particularly the story of one recently radicalized woman, Suzanne Zedet. She articulates the radical scope of the workers’ demands, which include access to the tools of cultural production.

76 minutes / b&w

French

Release: 2014

Copyright: 1969

Praise for A BIENTOT, J’ESPERE:

“Terrific!” —Professor Ellen Furlough, History Dept., University of Kentucky

“Effectively places us in the middle of the strike and offers intriguing insights into the motives of the workers and organizers…” —New York Magazine

Praise for CLASS OF STRUGGLE:

“One of the finest examples of the politically engaged French documentary cinema of the late Sixties. “—Sam DiIorio, Film Comment

“Fluent, energetic, and wide-ranging!” —Catherine Lupton, Chris Marker: Memories of the Future

“One of the great films of May of 1968.” —Paul Douglas Grant, Directory of World Cinema: France

“[The Medvedkin Group] would go on to make nearly a dozen films, some of them stunningly beautiful, most notably CLASS OF STRUGGLE.” —Min Lee, Film Comment

The Sixth Side of the Pentagon (La sixième face du Pentagone) + Far from Vietnam (Loin du Vietnam) + Introduction by Kodwo Eshun

Barbican 7.30pm 13 May 2014 Cinema 2/ Introduction by Kodwo Eshun

On October 21 1967, over 100,000 marchers assembled in Washington D.C. for the Mobilization to End the War in Vietnam protest. It was the largest anti-war gathering yet, bringing together a wide cross-section of liberals, radicals and hippies. For many, this marked the transition from simple anti-war demonstration to direct action that aimed to stop the war machine. Chris Marker was there with a camera.

France 1968 Dir Chris Marker 28 min

During the chilling and feverish year of 1967, an international collective of world-renowned filmmakers (including Jean-Luc Godard, Joris Ivens, William Klein, Claude Lelouch, Alain Resnais and Agnès Varda) came together in a spirit of bonhomie and common purpose to make this profoundly unapologetic anti-war film, which captured the mood of events to come in 1968.

France 1967 Dirs Jean-Luc Godard, Joris Ivens, William Klein, Claude Lelouch, Chris Marker, Alain Resnais, Agnès Varda 115 min

In collaboration with Whitechapel Gallery and Ciné Lumière. The Whitechapel hosts the first UK retrospective gallery exhibition of his work.

Chris Marker: A Grin Without a Cat – Curator’s Introduction, Whitechapel Gallery

Chris Marker is co-curated by Christine van Assche, Chief Curator, Centre Pompidou, Paris, writer and film critic Chris Darke, and Whitechapel Gallery Chief Curator Magnus Af Petersens.

Symposium: Chris Marker: In Memory, Part 1, Saturday 10th May

Holly Aylett will be introducing extracts from Marc Karlin’s For Memory (1982) in the Whitechapel Gallery’s Symposium: Chris Marker: In Memory, Part 1, Saturday 10th May – a series of presentations, screenings and discussions respond to the theme of memory, illustrating how the concept is interwoven throughout Marker’s life and work, providing new approaches to understanding Marker’s practice.

Class of Struggle (1969)

Cinema is not a magic.

It is a technic and a science.

A technic born from a science and set to a will.

Will that have the workers to release themselves.

In 1967, Chris Marker and Mario Marret (under the aegis of SLON) produced À BIENTÔT J’ESPÈRE, which documented a strike and factory occupation—the first in France since 1936—by textile workers at the Rhodiaceta textile plant in Besançon, the goals of which prefigured many of the demands that would come to define May 1968.

via Icarus Films

Icarus Films acquires Chris Marker’s LEVEL FIVE

April 09, 2014, New York: ICARUS FILMS today announced its acquisition of all North American distribution rights, including theatrical, non-theatrical, home entertainment, and television rights, to the LEVEL FIVE (106 minutes), Chris Marker’s 1996 feature film about a female video game developer, computer networks, and the Battle of Okinawa, in a new restoration.

While working on a game about the Battle of Okinawa, Laura, played with quiet intensity by Catherine Belkhodja, becomes increasingly drawn into her work and fascinated by the WWII battle that took place there, in which 150,000 Japanese were killed, many by suicide.

An elaborate, colorful patchwork of mesmerizing, pixelated images, fiction sequences with Belkhodja, archives, history, interviews (including with the Japanese director Nagisa Oshima), and quasi-science fiction, LEVEL FIVE prefigures the legendary auteur’s fascination with digital worlds, which he also explored in installations, interactive CD-ROMs, and later, digital platforms.

ICARUS FILMS plans a long-awaited LEVEL FIVE U.S. theatrical premiere release later this summer 2014 at BAMcinématek in New York, followed by a consumer DVD and digital release for home entertainment audiences.

The deal for North American distribution was negotiated by Jonathan Miller for Icarus Films and Florence Dauman of Argos Films (Paris, France).

LEVEL FIVE joins eighteen other films by Chris Marker that are distributed by Icarus Films, including LE JOLI MAI, FAR FROM VIETNAM, A GRIN WITHOUT A CAT, and ONE DAY IN THE LIFE OF ANDREI ARSENEVICH.

Via Icarus Films.

Vagrancy and drift: the rise of the roaming essay film

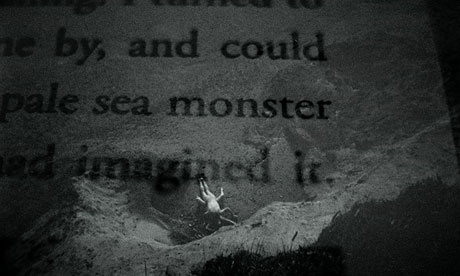

Freedom and possibility … a still from Grant Gee’s Patience (After Sebald) from 2011

by Sukhdev Sandhu. The Guardian, Saturday 3 August 2013

For years the essay film has been a neglected form, but now its unorthodox approach to constructing reality is winning over a younger, tech-savvy crowd.

For a brief, almost unreal couple of hours last July, in amid the kittens and One Direction-mania trending on Twitter, there appeared a very surprising name – that of semi-reclusive French film-maker Chris Marker, whose innovative short feature La Jetée (1962) was remade in 1995 as Twelve Monkeys by Terry Gilliam. A few months earlier, art journal e-flux staged The Desperate Edge of Now, a retrospective of Adam Curtis‘s TV films, to large audiences on New York’s Lower East Side. The previous summer, Handsworth Songs (1986), an experimental feature by the Black Audio Film Collective Salman Rushdie had once attacked as obscurantist and politically irrelevant, attracted a huge crowd at Tate Modern when it was screened shortly after the London riots.

Marker, Curtis, Black Audio: all have made significant contributions to the development of an increasingly powerful and popular kind of moving-image production: the essay film. Currently being celebrated in a BFI Southbank season entitled The Art of the Essay Film – curated by Kieron Corless of Sight and Sound magazine – it’s an elusive form with an equally elusive and speculative history. Early examples proposed by scholars include DW Griffith’s A Corner in Wheat (1909), Dziga Vertov’s Man with a Movie Camera (1929) and Jean Vigo‘s A Propos de Nice(1930), but some of its animating principles were identified in a key text, “The Film Essay” (1940) by the German artist Hans Richter, which called for documentaries “to find a representation for intellectual content” rather than merely “beautiful vistas”.

Essay films, unlike conventional documentaries, are only partly defined by their subject matter. They tend not to follow linear structures, far less to buttonhole viewers in the style of a PowerPoint presentation or a bullet-pointed memo; rather, in the spirit of Montaigne or even Hazlitt, they are often digressive, associative, self-reflexive. Just as the word essay has its etymological roots in the French “essai” – to try – essay film-makers commonly foreground the process of thought and the labour of constructing a narrative rather than aiming for seamless artefacts that conceal the conceptual questions that went into their making. Incompletion, loose ends, directorial inadequacy: these are acknowledged rather than brushed over.

Aldous Huxley once claimed an essay was “a literary device for saying almost everything about almost anything”. Essay films exploit this freedom and possibility, exulting in the opportunity to avoid the hermetic specialisation that characterises much academic scholarship, and to draw on ethnography, autobiography, philosophy and art history. A case in point is Otolith I (2003) by the Turner prize-nominated Otolith Group, whose co-founder Kodwo Eshun will deliver a keynote speech at BFI Southbank: it uses the mass demonstrations against the second Iraq conflict in London as an occasion to think about political collectivity, and deploys an elusive, eerily compelling compound of science fiction, travelogue, epistolary writing and leftist history to do so.

This roaming or tentacular approach to structure can be seen as a kind of territorial raid. Or perhaps essay film-makers are aesthetic refugees fleeing the austerities and repressions of dominant forms of cinema. It’s certainly striking how many essay films grapple with landscape and cartography: Patrick Keiller‘s London (1994) uses a fixed camera, a droll fictional narrator named Robinson and near-forensic socio-economic analysis to explore the “problem” of England’s capital; Los Angeles Plays Itself (2003) is an extraordinary montage film by Thom Andersen in which, sampling almost exclusively (unlicensed) clips from 20th-century cinema and with drily damning commentary, he critiques representations of his home city.

Essay films sometimes exhibit a quality of vagrancy and drift, as if they are not wholly sure of what they want to say or of the language they need to say it, which may stem from their desire to let subject matter determine – or strongly influence – filmic form. Here, as in the frequent willingness to blur the distinction between documentation and fabulation, the essay film has much in common with “creative non-fiction”. The literary equivalents of Hartmut Bitomsky, director of a mysterious investigation of dust, and Patricio Guzmán whose Nostalgia for the Light (2010) draws on astronomy to chart the poisonous legacies of Pinochet‘s coup d’etat in Chile, are writers such as Sven Lindqvist, Eduardo Galeano and Geoff Dyer. Perhaps it’s no coincidence that one of the most celebrated modern creative non-fiction authors was the subject of an equally ruminative, resonant essay film – Grant Gee’s Patience (After Sebald) (2011).

Essay film-makers – among them the Dziga Vertov Group (whose members included Jean-Luc Godard and Jean-Pierre Gorin) or the brilliant Santiago Álvarez – are often motivated by political concerns, but their work is never couched in the language of social realism or the journalistic dispatch. It is never purely utilitarian and is more likely to offer invitations to thought than clarion calls for action: Godard and Gorin’s Letter to Jane (1972) decodes at length a single still photograph of Jane Fonda on a trip to Vietnam; Black Audio Film Collective’sHandsworth Songs proposes that behind the blaring headlines of riot footage in the British media there lie the “ghosts of other stories”; Harun Farocki‘s Images of the World and Inscription of War (1988) explores the interplay of technology, war and surveillance. Essay films can be playful, but even when they are serious – as these three are – their approaches, at once rigorous and open-ended, are thrilling rather than pedagogic.

Just as literary critics used to lament that critical theory was taken more seriously in France than in the UK, the renown of essayists such as Marker, Godard and Agnès Varda (whose The Gleaners and I, a witty and moving meditation on personal, technological and socio-political obsolescence is a masterpiece) has served to obscure the range and history of British contributions to the genre: the sonically exploratory, surrealism-tinged likes of Basil Wright’s Song of Ceylon (1934) and Humphrey Jennings’s Listen to Britain (1942); Mike Dibb and John Berger’s Ways of Seeing (1972), which bears the imprint of Bertolt Brecht and Walter Benjamin; BS Johnson’s self-deconstructing Fat Man on a Beach (1973); Derek Jarman‘s exquisitely crepuscular Blue (1992), in which the director talks about and through his fading eyesight; and Marc Karlin’s resonant disquisition about cultural amnesia in For Memory (1986).

Some of these films started life on television, but these days it is the gallery sector that is more likely to commission or screen essay films, which are attracting ever more sizable audiences, especially younger people who have been weaned on cheap editing software, platforms such as Tumblr and the archival riches at YouTube and UbuWeb. Visually literate and semiotically savvy, they have tools – conceptual as well as technological – not only to critique and curate (moving) images, but to capture and assemble them. Having grown up in the era of LiveJournal and Facebook, they are also used to experimenting with personal identity in public; RSS feeds and news filters have brought them to a point where the essay film’s fascination with investigating social mediation and the construction of reality is second nature. It could well be that the essay film – for so long a bastard form, an unclassifiable and barely studied hybrid, opaque even to cinephiles – is ready to come into its own.