Tagged: Agnes Varda

VIDEO ESSAY: Reflexive Memories: The Images of the Cine-Essay by Nelson Carvajal

While the video essay form, in regards to its practice of exploring the visual themes in cinematic discourse, has seen a recent surge in popularity with viewers (thanks to invaluable online resources like indieWIRE’s Press Play, Fandor’s Keyframe and the academic peer-reviewed journal [in]Transition), its historical role as a significant filmmaking genre has long been prominent among film scholars and cinephiles.

From the start, the essay film—more affectionately referred to as the “cine-essay”—was a fusion of documentary filmmaking and avant-garde filmmaking by way of appropriation art; it also tended to employ fluid, experimental editing schemes. The first cine-essays were shot and edited on physical film. Significant works like Agnès Varda’s “Salut les Cubains” (1963) and Marc Karlin’s “The Nightcleaners” (1975), which he made in collaboration with the Berwick Street Film Collective, function like normal documentaries: original footage coupled with a voiceover of the filmmaker and an agenda at hand. But if you look closer and begin to study the aesthetics of the work (e.g. the prolific use of still photos in “Cubains,” the transparency of the “filmmaking” at hand in “Nightcleaners”), these films transcend the singular genre that is the documentary form; they became about the process of filmmaking and they aspired to speak to both a past and future state of mind. What the cine-essay began to stand for was our understanding of memory and how we process the images we see everyday. And in a modern technological age of over-content-creation, by way of democratized filmmaking tools (i.e. the video you take on your cell phone), the revitalization of the cine-essayists is ever so crucial and instrumental to the continued curation of the moving images that we manifest.

The leading figure of the cine-essay form, the iconic Chris Marker, really put the politico-stamp of vitality into the cine-essay film with his magnum-opus “Grin Without A Cat” (1977). Running at three hours in length, Marker’s “Grin” took the appropriation art form to the next level, culling countless hours of newsreel and documentary footage that he himself did not shoot, into a seamless, haunting global cross-section of war, social upheaval and political revolution. Yet, what’s miraculous about Marker’s work is that his cine-essays never fell victim to a dependency on the persuasive argument—that was something traditional documentaries hung their hats on. Instead, Marker was much more interested in the reflexive nature of the moving image. If we see newsreel footage of a street riot spliced together with footage from a fictional war film, does that lessen our reaction to the horrific reality of the riot? How do we associate the moving image once it is juxtaposed against something that we once thought to be safe or familiar? At the start of Marker’s “Sans Soleil” (1983), the narrator says, “The first image he told me about was of three children on a road in Iceland, in 1965. He said that for him it was the image of happiness and also that he had tried several times to link it to other images, but it never worked. He wrote me: one day I’ll have to put it all alone at the beginning of a film with a long piece of black leader; if they don’t see happiness in the picture, at least they’ll see the black.” It’s essentially the perfect script for deciphering the cine-essay form in general. It demands that we search and create our own new realities, even if we’re forced to stare at a black screen to conjure up a feeling or memory.

Flash forward to 1995: Harun Farocki creates “Arbeiter verlassen die Fabrik,” a video essay that foils the Lumière brothers’ “Employees Leaving the Lumière Factory” (1895) with countless other film clips of workers in the workplace throughout the century. It’s a significant work: exactly 100 years later, a cine-essayist is speaking to the ideas of filmmakers from 1895 and then those ideas are repurposed to show a historical evolution of employer-employee relations throughout time. What’s also significant about Farocki’s film is the technological aspect. Note how his title at this point in time is a “video essayist.” The advent of video, along with the streamlined workflow to acquiring digital assets of moving images, gave essayist filmmakers like Farocki the opportunity for creating innovative works with faster turnaround times. Not only was it less cumbersome to edit footage digitally, the ways for the works to be presented were altered; Farocki would later repurpose his own video essay into a 12-monitor video installation for exhibition.

Consider Thom Andersen’s epic 2003 video essay “Los Angeles Plays Itself.” In it, Andersen appropriates clips from films set in Los Angeles from over the decades and then criticizes the cinema’s depiction of his beloved city. It’s the most meta of essay films because by the end, Andersen himself has constructed the latest Los Angeles-based film. And although Andersen has more of an obvious thesis at hand than, say something as equally lyrical and dense as Marker’s “Sans Soleil,” both films exist in the same train of thought: the exploration of the way we as viewers embrace the moving image and then how we communicate that feeling to each other. Andersen may be frustrated with the way Hollywood conveys his city but he even he has moments of inspired introspection towards those films. The same could be said of Marker’s work; just as Marker can remain a perplexed and often inquisitive spectator of the moving images of poverty and genocide that surround him, he functions as a gracious, patient guide for the viewer, since it is his essay text that the narrator reads from.

Watching an essay film requires you to fire on all cylinders, even if you watch one with an audience. It’s a different kind of collective viewing because the images and ideas spring from an artifact that is real; that artifact can be newsreel footage or a completed, a released motion picture that is up for deeper examination or anything else that exists as a completed work. In that sense, the cine-essay (or video essay), remains the most potent form of cinematic storytelling because it invites you to challenge its ideas and images and then in turn, it challenges your own ideas by daring you to reevaluate your own memory of those same moving images. It aims for a deeper truth and it dares to repurpose the cinema less as escapist entertainment and more as an instrument to confront our own truths and how we create them.

via Balder & Dash

Agnès Varda on Coming to California

Agnès Varda stopped by the Criterion offices to talk about the films she made in California in the sixties and eighties. They are all collected in the new Eclipse series Agnès Varda in California, available now!

The legendary French filmmaker Agnès Varda, whose remarkable career began in the 1950s and has continued into the twenty-first century, produced some of her most provocative works in the United States. After temporarily relocating to California in the late sixties with her husband, Jacques Demy, Varda, inspired by the politics, youth culture, and sunshine of the San Francisco and Los Angeles areas, created three works that use documentary and fiction in various ways. She returned a decade later, and made two other fascinating portraits of outsiderness. Her five revealing, entertaining California films, encompassing shorts and features, are collected in this set, which demonstrates that Varda was as deft an artist in unfamiliar terrain as she was on her own turf.

The Sixth Side of the Pentagon (La sixième face du Pentagone) + Far from Vietnam (Loin du Vietnam) + Introduction by Kodwo Eshun

Barbican 7.30pm 13 May 2014 Cinema 2/ Introduction by Kodwo Eshun

On October 21 1967, over 100,000 marchers assembled in Washington D.C. for the Mobilization to End the War in Vietnam protest. It was the largest anti-war gathering yet, bringing together a wide cross-section of liberals, radicals and hippies. For many, this marked the transition from simple anti-war demonstration to direct action that aimed to stop the war machine. Chris Marker was there with a camera.

France 1968 Dir Chris Marker 28 min

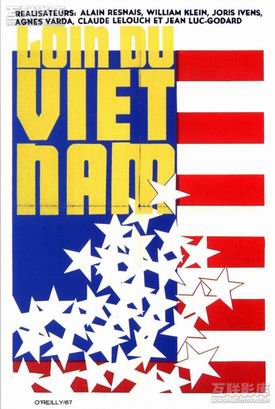

During the chilling and feverish year of 1967, an international collective of world-renowned filmmakers (including Jean-Luc Godard, Joris Ivens, William Klein, Claude Lelouch, Alain Resnais and Agnès Varda) came together in a spirit of bonhomie and common purpose to make this profoundly unapologetic anti-war film, which captured the mood of events to come in 1968.

France 1967 Dirs Jean-Luc Godard, Joris Ivens, William Klein, Claude Lelouch, Chris Marker, Alain Resnais, Agnès Varda 115 min

In collaboration with Whitechapel Gallery and Ciné Lumière. The Whitechapel hosts the first UK retrospective gallery exhibition of his work.

Vagrancy and drift: the rise of the roaming essay film

Freedom and possibility … a still from Grant Gee’s Patience (After Sebald) from 2011

by Sukhdev Sandhu. The Guardian, Saturday 3 August 2013

For years the essay film has been a neglected form, but now its unorthodox approach to constructing reality is winning over a younger, tech-savvy crowd.

For a brief, almost unreal couple of hours last July, in amid the kittens and One Direction-mania trending on Twitter, there appeared a very surprising name – that of semi-reclusive French film-maker Chris Marker, whose innovative short feature La Jetée (1962) was remade in 1995 as Twelve Monkeys by Terry Gilliam. A few months earlier, art journal e-flux staged The Desperate Edge of Now, a retrospective of Adam Curtis‘s TV films, to large audiences on New York’s Lower East Side. The previous summer, Handsworth Songs (1986), an experimental feature by the Black Audio Film Collective Salman Rushdie had once attacked as obscurantist and politically irrelevant, attracted a huge crowd at Tate Modern when it was screened shortly after the London riots.

Marker, Curtis, Black Audio: all have made significant contributions to the development of an increasingly powerful and popular kind of moving-image production: the essay film. Currently being celebrated in a BFI Southbank season entitled The Art of the Essay Film – curated by Kieron Corless of Sight and Sound magazine – it’s an elusive form with an equally elusive and speculative history. Early examples proposed by scholars include DW Griffith’s A Corner in Wheat (1909), Dziga Vertov’s Man with a Movie Camera (1929) and Jean Vigo‘s A Propos de Nice(1930), but some of its animating principles were identified in a key text, “The Film Essay” (1940) by the German artist Hans Richter, which called for documentaries “to find a representation for intellectual content” rather than merely “beautiful vistas”.

Essay films, unlike conventional documentaries, are only partly defined by their subject matter. They tend not to follow linear structures, far less to buttonhole viewers in the style of a PowerPoint presentation or a bullet-pointed memo; rather, in the spirit of Montaigne or even Hazlitt, they are often digressive, associative, self-reflexive. Just as the word essay has its etymological roots in the French “essai” – to try – essay film-makers commonly foreground the process of thought and the labour of constructing a narrative rather than aiming for seamless artefacts that conceal the conceptual questions that went into their making. Incompletion, loose ends, directorial inadequacy: these are acknowledged rather than brushed over.

Aldous Huxley once claimed an essay was “a literary device for saying almost everything about almost anything”. Essay films exploit this freedom and possibility, exulting in the opportunity to avoid the hermetic specialisation that characterises much academic scholarship, and to draw on ethnography, autobiography, philosophy and art history. A case in point is Otolith I (2003) by the Turner prize-nominated Otolith Group, whose co-founder Kodwo Eshun will deliver a keynote speech at BFI Southbank: it uses the mass demonstrations against the second Iraq conflict in London as an occasion to think about political collectivity, and deploys an elusive, eerily compelling compound of science fiction, travelogue, epistolary writing and leftist history to do so.

This roaming or tentacular approach to structure can be seen as a kind of territorial raid. Or perhaps essay film-makers are aesthetic refugees fleeing the austerities and repressions of dominant forms of cinema. It’s certainly striking how many essay films grapple with landscape and cartography: Patrick Keiller‘s London (1994) uses a fixed camera, a droll fictional narrator named Robinson and near-forensic socio-economic analysis to explore the “problem” of England’s capital; Los Angeles Plays Itself (2003) is an extraordinary montage film by Thom Andersen in which, sampling almost exclusively (unlicensed) clips from 20th-century cinema and with drily damning commentary, he critiques representations of his home city.

Essay films sometimes exhibit a quality of vagrancy and drift, as if they are not wholly sure of what they want to say or of the language they need to say it, which may stem from their desire to let subject matter determine – or strongly influence – filmic form. Here, as in the frequent willingness to blur the distinction between documentation and fabulation, the essay film has much in common with “creative non-fiction”. The literary equivalents of Hartmut Bitomsky, director of a mysterious investigation of dust, and Patricio Guzmán whose Nostalgia for the Light (2010) draws on astronomy to chart the poisonous legacies of Pinochet‘s coup d’etat in Chile, are writers such as Sven Lindqvist, Eduardo Galeano and Geoff Dyer. Perhaps it’s no coincidence that one of the most celebrated modern creative non-fiction authors was the subject of an equally ruminative, resonant essay film – Grant Gee’s Patience (After Sebald) (2011).

Essay film-makers – among them the Dziga Vertov Group (whose members included Jean-Luc Godard and Jean-Pierre Gorin) or the brilliant Santiago Álvarez – are often motivated by political concerns, but their work is never couched in the language of social realism or the journalistic dispatch. It is never purely utilitarian and is more likely to offer invitations to thought than clarion calls for action: Godard and Gorin’s Letter to Jane (1972) decodes at length a single still photograph of Jane Fonda on a trip to Vietnam; Black Audio Film Collective’sHandsworth Songs proposes that behind the blaring headlines of riot footage in the British media there lie the “ghosts of other stories”; Harun Farocki‘s Images of the World and Inscription of War (1988) explores the interplay of technology, war and surveillance. Essay films can be playful, but even when they are serious – as these three are – their approaches, at once rigorous and open-ended, are thrilling rather than pedagogic.

Just as literary critics used to lament that critical theory was taken more seriously in France than in the UK, the renown of essayists such as Marker, Godard and Agnès Varda (whose The Gleaners and I, a witty and moving meditation on personal, technological and socio-political obsolescence is a masterpiece) has served to obscure the range and history of British contributions to the genre: the sonically exploratory, surrealism-tinged likes of Basil Wright’s Song of Ceylon (1934) and Humphrey Jennings’s Listen to Britain (1942); Mike Dibb and John Berger’s Ways of Seeing (1972), which bears the imprint of Bertolt Brecht and Walter Benjamin; BS Johnson’s self-deconstructing Fat Man on a Beach (1973); Derek Jarman‘s exquisitely crepuscular Blue (1992), in which the director talks about and through his fading eyesight; and Marc Karlin’s resonant disquisition about cultural amnesia in For Memory (1986).

Some of these films started life on television, but these days it is the gallery sector that is more likely to commission or screen essay films, which are attracting ever more sizable audiences, especially younger people who have been weaned on cheap editing software, platforms such as Tumblr and the archival riches at YouTube and UbuWeb. Visually literate and semiotically savvy, they have tools – conceptual as well as technological – not only to critique and curate (moving) images, but to capture and assemble them. Having grown up in the era of LiveJournal and Facebook, they are also used to experimenting with personal identity in public; RSS feeds and news filters have brought them to a point where the essay film’s fascination with investigating social mediation and the construction of reality is second nature. It could well be that the essay film – for so long a bastard form, an unclassifiable and barely studied hybrid, opaque even to cinephiles – is ready to come into its own.

Chris Marker: Marc 2

In a post last year, I traced the lost history of Marc Karlin’s collaborations with Chris Marker. It is over a year since Marker’s death and in tribute, stirred by the BFI’s Film Essay season in August, here is a collection of Marker related videos. Firstly, a visual essay from Criterion exploring the soundscape of Chris Marker’s 1962 landmark La Jetée, written by Michael Koresky of Reverse Shot.

Codirected by Frank Simeone and John Chapman, Junkopia was filmed at the Emeryville Mudflats outside of San Francisco while Chris Marker was also shooting the Vertigo sections of Sans Soleil.

Toute la mémoire du monde (1956) is a 20 minute bout of archive fever administered by Alain Resnais. Resnais takes us behind the scenes of the Bibliothèque nationale de France in Paris, conceiving a key theme of the film essayist; the fragility of memory and the need to remember. In the opening credits Marker, a man of many aliases, is introduced as Chris the Magic Marker – that most democratic of public writing tools as Finn Burton puts it in Future Anterior,

That Resnais documentary follows one book into the Bibliothèque Nationale and thence into the hands of a reader, and the book happens to be one of the Petite Planète series of travel books, a series founded and edited (1954–58) by Marker. ‘Not a guidebook,’ Marker promised, ‘not a history book, not a propaganda brochure, not a traveller’s impressions, but instead equivalent to the conversation we would like to have with someone intelligent and well-versed in the country that interests us.’ Perhaps, then, something like the letters Sandor Krasna sends from his travels to his unnamed correspondent (voiced with limpid calm by Alexandra Stewart) in Sans-soleil (1983). Marker did much of the graphic design and layout work for the series as well, and every cover was a different picture of a woman, some looking away and lost in their own thoughts, others gazing into the camera, reserved and enigmatic. In Remembrance of Things to Come (2001), Alexandra Stewart, speaking again on behalf of Marker, says of the work of Denise Bellon, ‘Being a photographer means not only to look but to sustain the gaze of others.’ ‘Have you heard of anything stupider’, she says, quoting a letter of Krasna’s from Fogo in the Cape Verde islands, ‘than to say to people, as they teach in film schools, not to look at the camera?’ There is a woman, gazing slightly off-camera, on the cover of the Petite Planète edition (#25) that has arrived for cataloging in the Resnais film. Her hair is in an elegant black bob, she wears a simple black garment; the book, its title announces, is a traveller’s guide to Mars. She is perhaps the first of Marker’s many characters who address us, unexpectedly, from the future. They look back on our present moment and, in doing so, transform it, as we now transform the past, our memories, our recordings. (‘I wonder how people remember things who don’t film, don’t photograph, don’t tape.’)

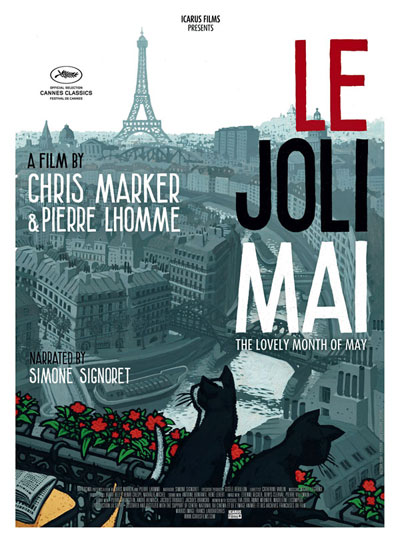

In April Icarus Films announced its acquisition of all North American distribution rights to Chris Marker and Pierre Lhomme’s landmark 1963 film Le joli mai. This film had been unavailable for many years and it is now newly restored. It will be screened at several major film festivals and premiered in New York at Film Forum on September 13, 2013, presented in DCP, made from a new 2K scan. The restoration work on Le joli mai was done according to the wishes of Chris Marker and supervised by Pierre Lhomme, the film’s cinematographer and co-director. First off is Lhomme commenting on the restoration process, followed by the new trailer.

LE JOLI MAI is a portrait of Paris and Parisians shot during May 1962. It is a film with several thousand actors including a poet, a student, an owl, a housewife, a stockbroker, a competitive dancer, two lovers, General de Gaulle and several cats. Filmed just after the March ceasefire between France and Algeria, LE JOLI MAI documents Paris during a turning point in French history: the first time since 1939 that France was not involved in any war. Icarus Films

In Sight & Sound’s glorious celebration of the life and work of Chris Marker last year (Vol. 22 Issue 10 Oct 2012), a number of filmmakers, including Jem Cohen, Thom Anderson, Patrick Keiller, Chris Petit, Sarah Turner and Kodwo Eshun, paid tribute to the man. The US filmmaker John Gianvito proclaimed that any filmmaker who has ventured into the film essay territory in the past 55 years owes a great debt to Marker, and befittingly includes Marc Karlin. Introduced to Karlin’s work by Marker, Gianvito states Karlin is in need of the same recovery Marker bestowed the Soviet filmmaker Alexander Medvedkin.

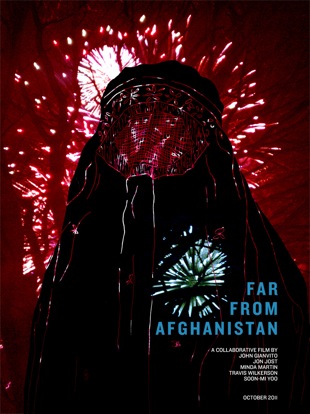

John Gianvito’s most recent ouput is the collective film Far From Afganistan (2012), made with filmmakers Travis Wilkerson, Jon Jost, Minda Martin and Soon-Mi Yoo. The film is clearly inspired by Loin Du Vietnam (Far from Vietnam) (1967), a collaboration between Alain Resnais, Claude Lelouch, Jean-Luc Godard, William Klein, Joris Ivens, and Agnès Varda, conceived as an outcry against the Vietnam War. Marker edited together William Klein’s films of pro- and anti-war protests in New York, Joris Ivens’ own North Vietnam footage; additional material by Agnès Varda and Claude Lelouch and Resnais and Godard’s self-contained sequences. From this prototype, Far From Afghanistan mixes fictional narrative, found footage and reportage in response to a protracted war that remains far from the collective consciousness. Here are both trailers, side by side. (Look out for Marker’s owl in Far From Afghanistan).

Next is a video postcard Agnes Varda made for her friend Chris Marker presented at the Rencontres de la Photographie in Arles in 2011 and her glimpse inside Marker’s studio. Marc Karlin too describes Marker’s studio upon a visit around the editing period of Le Fond de l’air est rouge (1977).

“Chris had a garage, a huge studio with drainpipes all across it. It was vast, and he put these little rolls of films all along the drainpipes, and then divided it onto countries, so you had Columbia, Peru, Cuba, Africa and so on. I entered this garage to find all these films from all these countries: the whole world was there. Right at the end there was Chris Marker on a platform with his editing table, and he looked like God. You had to walk past these films to reach him and sit down”.

Last year in an article written for Sight & Sound, Patrico Guzman recalled his first meeting with Marker and recounts his debt of gratitude that he owes to his mentor while filming Because The First Year. Nine years before their first meeting, Guzman and Marker collaborated, from a distance (Guzman with camera and Marker on script) on Joris Iven’s film …A Valparaíso (1962).

In 1962 Joris Ivens was invited to Chile for teaching and filmmaking. Together with students he made … A Valparaiso, one of his most poetic films. Contrasting the prestigious history of the seaport with the present the film sketches a portret of the city, built on 42 hills, with its wealth and poverty, its daily life on the streets, the stairs, the rack railways and in the bars. Although the port has lost its importance, the rich past is still present in the impoverished city. The film echoes this ambiguous situation in its dialectical poetic style, interweaving the daily life reality (of 1963) with the history of the city and changing from black and white to colour, finally leaving us with hopeful perspective for the children who are playing on the stairs and hills of this beautiful town. ivens.nl

And finally… a glimpse of Christian François Bouche-Villeneuve, alias Sandor Krasna, alias Hayao Yamaneko, alias Kosinski, alias Guillaume-en-Egypte, alias Sergei Murasaki, alias Chris Marker…

Further Reading:

http://strangewood.tumblr.com/tagged/Chris%20Marker

http://www.fandor.com/blog/daily-chris-marker-1921-2012

http://www.filmcomment.com/article/chris-marker-the-truth-about-paris

http://www.criterion.com/current/posts/2246-cinematography-by-pierre-lhomme

I Am Writing To You From A Distant Country… Marc and Marker (The Monk/L’maître).

Just before Marc Karlin’s death, film-maker Isaac Julien remarked, ‘The reason why his (Karlin’s) work is still screened, is because he is seen as like the Chris Marker or Jean Luc Godard of the British independent scene. He was more or less the only person representing that sort of voice, that sort of perspective’.

Indeed Marker’s reflection on images, the media and their relationship with memory and with human subjectivity are themes shared by Karlin. And in terms of form, both film-makers are key to deploy alternating commentaries on history and society, with private musings and recollections. It is a voice that constantly shifts in linguistic registers, adopting poetic and prosaic tones in order to shake an amnesia strikened history.

Marc called Marker ‘The Monk’, on account of his reclusive nature and mythical standing with his contemporaries. Up until his death last month, Marker rarely granted interviews, opting to leave calling cards such as pictures of cats or owls. It is clear that Marker was a key influence on Marc, but what has been forgotten is Marc Karlin and Chris Marker were actually long-standing-collaborators. He met Marker during May ’68 while Marker was working on Cine-Tracts (1968) with Jean-Luc Godard. Marker had just formed his film group SLON and had since released Far from Vietnam (1967),a collective cinematic protest with offerings from Jean-Luc Godard, Alain Resnais and Agnes Varda, inspired by the film-making practices of the Soviet film-maker, Alexander Medvedkin.

Born in 1900, Medvedkin was little known outside of his homeland unlike his contemporaries, Sergei Eisentstein and Dziga Vertov. Marker was drawn to Medvedkin after viewing his film Happiness (1934) in 1961, a satirical fantasy that promoted the benefits of collectivisation. The American writer Jay Leyda, who wrote Kino: A History Of The Russian And Soviet Film, introduced Marker to Medvedkin at the Leizig Film Festival in November 1967. This meeting resulted in Marker’s next film, Le Train en marche (1971) an attempt to explain the myth of Medvedkin’s kino-poezd/cine train, the impact it had on cinema and the practices it could inspire in democratic film-making.

Medvedkin saw his kino-poezd (294 days on the rails, 24,565m of film projected, 1000km covered) as a means of revolutionising the consciousness of the Soviet Union’s rural dwellers. Marker hoped his recent unearthing would incite similar political film-making. In London, Karlin and other kindred spirits joined Cinema Action.” There was a relationship to the Russians. Vertoz, the man and the movie camera, Medvedkin, and his agitprop Russian train; the idea of celebrating life and revolution on film, and communicating that. Medvedkin had done that by train. SLON and Cinema Action both did it by car. Getting a projector, putting films in the boot, and off you went and showed films – which we did”.

Marc recalls being asked to shoot the English version of Marker’s The Train Rolls On in the mid-1970s. “If Chris asked you to do something you did it: There was no question”. Marker instructed Marc to film at Peugeot car factory, where Marker wanted to make a film on car workers. He couldn’t go in person as he was known to the officials as an agitator. Working under the pretense he was making a film for the Common Market, Peugeot responsed by putting Marc and his crew in a luxury hotel in Paris.

Choosing not to approach filming the monotonous labour of the workers in a Godardian way, Marc found inspiration in how the workers for a few seconds would cease work,

“all they did was boom, boom, boom. Then I noticed that the workers on the assembly line would come up like fish for air. They would not touch, and they would open their mouths. The Peugeot people were so canny, because they would put together a Moroccan, Portuguese, French and an Italian, so no one could actually speak to each other because on one knew each other’s lanuguage. That was why an excessive amount of touching was going on. I said to the cameraman, ‘Look, that’s how we film. We don’t film the work, because we can show that in twenty or thirty seconds. But we can film these people gasping for air. Or touching, whatever’. That is what we filmed. And then the audience had to imagine. What does it take for somebody to come up for air like that? Or touch? Those are the questions; when you talk about images of labour, how do you film labour?”

In the mid 1970s, Marker contacted left-wing filmmakers and groups to send him their offcuts. As Marker was ‘le maitre’, Marc agreed. Here Marc describes Marker’s studio upon a visit, “Chris had a garage, a huge studio with drainpipes all across it. It was vast, and he put these little rolls of films all along the drainpipes, and then divided it onto countries, so you had Columbia, Peru, Cuba, Africa and so on. I entered this garage to find all these films from all these countries: the whole world was there. Right at the end there was Chris Marker on a platform with his editing table, and he looked like God. You had to walk past these films to reach him and sit down”.

The film became Le fond de l’air est rouge (1977). It focused on the doomed optimism of left-wing activism from the second half of the 20th century. The ‘red in the air’ implying the socialist project only existed in the air, communicated only by a dream language. Again, Marc did the English version, A Grin without a Cat (1988) for Channel 4. Running shorter than Marker’s film and adding a new voice cast including Jim Broadbent and Cyril Cusack.

A Grin Without A Cat Channel 4 Contract. © The Marc Karlin Archive

Around this time, Marc, in need of political inspiration, wanted to make a film about Chris Marker that would use Marker’s images, entitled, I Am Writing To You From A Distant Country… In keeping with Marker’s style, it begins with a letter followed by a montage of stills and sequences from Letters From Siberia (1957), Le joli mai (1963), La jetée (1962) and Le fond de l’air est rouge (1977) . From the treatment, we see the intention – to locate a time-travelling Marker. Marc asks, who is this letter writer and traveller? How do we recognise him?.. What does he declare at customs? There are no photographs of him, no evidence other than his letters. He is a Martian, an astronaut, an 18th century time-traveller, a descendant of Vikings, a Marxist, a subversive, an old man of letters… There are traces but no apparition, we have the grin but no cat. But we know where he lives: in a house in Neuilly, painted outside with owls whose eyes glint in the dark…

Here is a rather faded, time travelling letter from Marc to the Monk, informing him of the project. It comes at a time where Marc is creatively and politically jaded – in ‘Thatcher’s trough’.

Letter to Chris Marker. © The Marc Karlin Archive

The film never materialised, undoubtedly sucked into a black hole. Undettered, Marc ploughed into his next project, Between Times (1993). Possessing dialectic discsussive voice-overs, Between Times is a clear nod to Marker. The film’s main focus is on the Thurcroft miners failed attempt to buy their colliery from British Coal and the search for fresh alternatives after the devisive general election defeat for the left in 1992. This new perspective draws optimism from the educational ethos at Northern College, a residential college dedicated to the education and training of men and women who are without formal qualifications. The film observes a key moment in the shifting attitudes and aspirations among the working class in Britain at the time and recalls a May ’68 slogan,

le pain pour tous mais aussi / bread for all but

La paix/peace

le rire/laughter

le théâtre/theatre

la vie/life

The slogan is actually taken from a strike in March 1967 at the Rhodiaceta textile factory in Bresancon, France. The workers were not merely demanding higher wages but challenging the core oppression within capitalist society; wages yes, but what about education and cultural life? Chris Marker entered the strike on March 8 1967, resulting in the documentary À bientôt, j’espère (1967) (see below, sorry no Eng Subs) filmed by Marker between March 1967 and January 1968 with the Communist filmmaker Mario Marret and the SLON team.

As Trevor Stark points out in his excellent essay, “Cinema in the Hands of the people”; Chris Marker, the Medvedkin Group, and the Potential of Militant film, the film À bientôt, j’espère emphasises the liberating experience of laying claim to sectors of life inaccessible to the worker: to creativity, to culture, to communication. Forty-two minutes into the documentary we see Pol Cébé, a factory worker from the working class district of Palente-les-Orchamps who had established a cultural programme for the local community and had regenerated the factory’s library with classic Marxist and Communist texts, in close-up state,

For us culture is a struggle, a claim. Just as with the right to have bread and lodgings, we claim the right to culture – it’s the same fight for culture as for union or in the political field.

À bientôt, j’espère is left purposley open-ended with little resolution, marked tellingly by Pol Cébé reciting the documentary’s title À bientôt, j’espère – ‘Hope To See You Soon’. The strike at Rhodiaceta achieved nothing but the broadening of class concsiousness that consequently lit the test paper for the events in Paris the following May. These concerns are resuscitated in Between Times. The miners are halted in their plan to buy their colliery and are pointed to the development of technology for optimism. Sadly, Marc Karlin observes the irony that before, a dream language could still be spoken, now the dreams are possible we no longer know how to speak it. Like À bientôt, j’espère, Between Times ends without a dialectical antithesis, leaving all but tension.

So he decided to keep his voices, make them argue, merge, split again. Be on high and on the ground. Anything to keep that sleepy logic at bay. But then there were those who were doing this all along…

These words are spoken over a slow tracking shot of a wildlife garden revealing in the foreground, a golden egg – Marker’s owl.

Sources

Looking at Class. Film, Television and the Working Class in Britain, S, Rowbotham & H, Beynon, (Rivers Oram Press:2001)

The Personal Camera: Subjective Cinema and the Essay Film, L, Rascaroli, (Columbia University Press:2009)

Chris Marker: Memories of the Future, C, Lupton, (Reaktion Books:2004)

Kino: A History of the Russian and Soviet Film, J, Leyda (Princeton University Press:1983)

“Cinema in the Hands of the people”; Chris Marker, the Medvedkin Group, and the Potential of Militant film, T, Stark, (mitpressjournals:2012)