Tagged: Marc Karlin

The Poor Stockinger, The Luddite Cropper and the Deluded Followers of Joanna Southcott

The Poor Stockinger, The Luddite Cropper and the Deluded Followers of Joanna Southcott is a new film from artist Luke Fowler, recently shortlisted for the Turner Prize. Fowler’s film is inspired by the life of the critic, historian and activist E.P. Thompson and is showing at The Hepworth Wakefield.

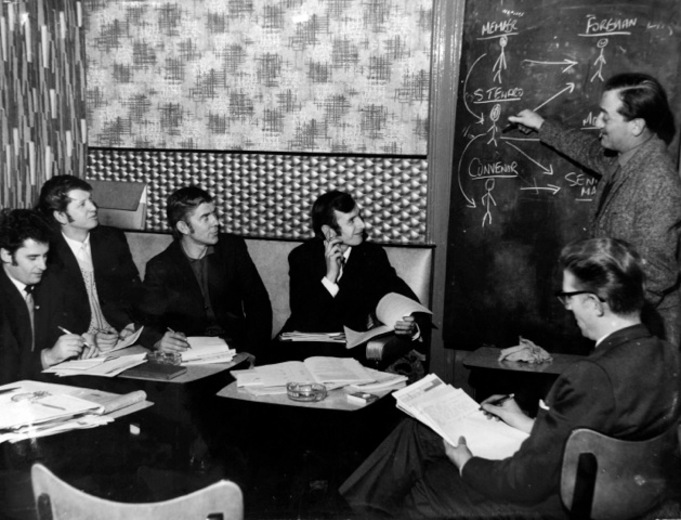

It focuses on Thompson’s early years at the University of Leeds to his longstanding commitment to the Workers’ Education Association (WEA) in the West Riding of Yorkshire, teaching classes in literature and history to miners, factory workers and the unemployed. The film explores the issues that were at stake for educationalists at that time, a struggle that resonates today within the current market-led higher education system. Many, like Thompson, wanted to use teaching to create ‘revolutionaries’ and pursue the original WEA values of delivering a ‘socially purposeful’ education for working class communities. This was opposed by those within the Department who wished to foster students with an ‘objective’, ‘calm’ and ‘tolerant’ attitude. The film centres on this argument, set out by Thompson in an internally circulated document entitled ‘Against University Standards’ (1950).

Fowler’s film offers a timely reminder to a forgotten history, connecting us with political ideas, sentiments and language that are excluded, even unmentionable, in today’s prevailing culture. In an interview with The Herald, Fowler states,

“Most working-class people from Wakefield today will struggle to see how a seemingly marginal academic debate in the 1940s is relevant to their life now, but I see it as relevant because of what is happening to education now, because education has been turned into a business, and I still long for a time when education isn’t seen as that, isn’t corralled by free market ideology.”

He adds, “It’s tragic when you look at the rhetoric of universities and the WEA and now . . . the values that these people had, the idealism, and how that has been reversed. The idea that you could have education for free, that was non-utilitarian, non-vocational, and not an individualistic view, it was about raising the whole standards of the class. They were against social mobility, against the idea of the ‘ladder’, and against the idea of teaching to make the workforce more efficient or to increase productivity.”

In the Poor Stockinger, Fowler integrates footage of a speech by E.P Thompson from Marc Karlin’s For Memory (1982). Similarly, Marc Karlin was keen to explore the theme of memory; how it is preserved and handed on, and how dissident recollections are blocked and contained. The non-conforming voices in For Memory (1982) consist of anti-fascist fighters at Cable Street and Clay Cross miners. E.P Thompson’s segment in For Memory is filmed at Burford Church, giving a lecture on three Levellers who were shot there in the 17th Century for refusing to fight for Cromwell’s New Model Army campaign in Ireland.

Karlin recalls, ‘I can’t give you a reason why I felt the whole thing was somehow tottering, about to roll. What is funny is that when Edward Thompson is speaking there is a green banner behind him. He talks about rosemary being the flower of remembrance, at that point suddenly the green banner collapses. A unique left thing, we are never able to pin up anything properly. Everything’s fragile, unless you store it, keep it and communicate it’.

The Poor Stockinger, The Luddite Cropper and the Deluded Followers of Joanna Southcott is now screening at The Hepworth Wakefield until 14th October.

Sources

Looking at Class. Film, Television and the Working Class in Britain, S, Rowbotham & H, Beynon, (Rivers Oram Press:2001)

http://www.heraldscotland.com/arts-ents/visual/lesson-for-our-age.1340330661

Dead Man’s Wheel and American Choice ’68 (1968)

In an interview with Sheila Rowbotham, published in her book Looking at Class. Film, Television and the Working Class in Britain written with Huw Beynon, Marc Karlin recalls his early films of the late 1960s before he entered into collective film-making with Cinema Action and the Berwick Street Collective . Sadly, no prints or negatives have been found in the Karlin’s film and video archive. This tantalising interview is the only lead so far.

Marc spent most of his childhood in Paris, Le Perreux. After being schooled in England, he later returned and became embroiled in the events of May 1968. A few years earlier, Marc filmed a conversation with an American deserter from the Vietnam War, Philip Wagner, who had landed in London on behalf of the Stop It Committee. By 1968, Wagner was in Paris. Marc, having been dissatisfied with the first film, decided to film Wagner again, this time with a French deserter from the Algeria War.

The film was called American Choice ’68. When he began to edit the film May 68 exploded. There was a strike of editors, who promptly sent Marc to a railway depot to ‘shoot reels for the revolution’. He struck up a friendship with a train driver and began filming him. The film was called Dead Man’s Wheel and focuses on the driver’s incredibly repetitive work routine. The film ends with the driver explaining this to students at the Sorbonne.

Karlin describes the scene, ‘He started explaining his work to the students, miming what he did in the train. Every fifteen seconds he had to clasp and unclasp the wheel, otherwise the train would stop. It was to stop him falling asleep and was called ‘dead man’s wheel’: he explained how ill the drivers were, because of this every fifteen seconds. It just tortured them. As he explains this, you can see the camera going round the students: they are completely bog-eyed about the worker, May 1968, the possibilities, the world that he came from. It was a hell of an introduction for me, that moment. A moment that you try to expand for years and years – but obviously you can’t‘.

In Marc’s obituary John Wyver writes the film ‘combines a deep respect for one human being with an analysis of one political, social and cultural moment’. Marc states he was very proud of the film and reveals it was shown at the NFT and remained popular in France. The hunt continues.

Sources – Looking at Class. Film, Television and the Working Class in Britain, S, Rowbotham & H, Beynon, (Rivers Oram Press:2001)

British Sounds and Echoes

In the recent Marc Karlin round-table event at Picture This, Kodwo Eshun remarked this project reflected a current need to return to the archives of what Jean-Luc Godard named ‘Cine-Marxism’. Sheila Rowbotham, the Writer in Residence at the Eccles Centre for American Studies in the British Library and friend of Marc Karlin, was also on the panel. Here is a story where all these figures overlap.

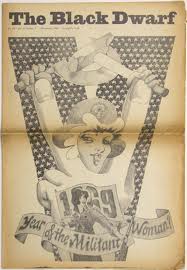

In 1969 Jean-Luc Godard was in London filming British Sounds, a project he was making with Kestral Films for London Weekend Television. He approached Sheila Rowbotham for permission to use her Black Dwarf article, ‘Women: the struggle for Freedom’ written in January 1969 with the front page ‘1969: Year of the Militant Woman?’. His idea was to film her with nothing on reciting words of emancipation as she walked up and down a flight of stairs – the supposition being that eventually the voice would override the images of the body. Rowbotham declined. Consequently, another young woman agreed to walk up and down the stairs and Rowbotham did the voiceover. Here’s a section of the film.

This is an edited extract from Sheila Rowbotham’s memoir ‘Promise of a Dream’ describing the exchange with Godard.

Godard came to Hackney to convince me. He sat on the sanded floor of my bedroom, a slight dark man, his body coiled in persuasive knots. Neither Godard the man nor Godard the mythical creator of A Bout de Souffle, which I’d gone to see with Bar in Paris, were easy to contend with. I perched in discomfort on the edge of my bed and announced, ‘I think if there’s a woman with nothing on appearing on the screen no one’s going to listen to any words,’ suggesting perhaps he could film our ‘This Exploits Women’ stickers on the tube. Godard gave me a baleful look, his lip curled. ‘Don’t you think I am able to make a cunt boring?’ he exclaimed. We were locked in conflict over a fleeting ethnographic moment.

British Sounds was to have an unexpected series of repercussions which I did not grasp at the time. Humphrey Burton, then head of arts at London Weekend Television, refused to show it. The ensuing row fused with the sacking of Michael Peacock from the board of LWT in September 1969. Whereupon Tony Garnett and Kenith Trodd from Kestral, along with other programme-makers, resigned in protest. LWT decided to go for higher ratings and bought in an Australian newspaper owner called Rupert Murdoch. The last thing he wanted to do was to make a cunt boring.

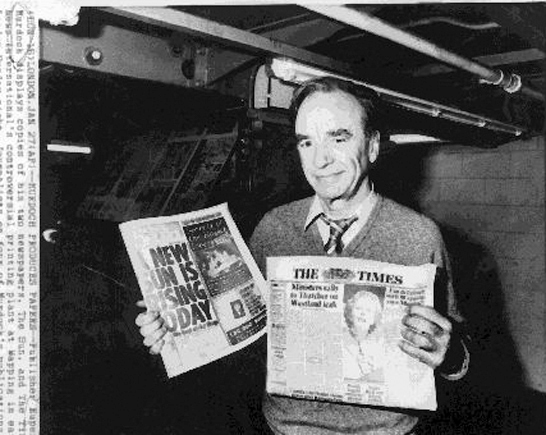

This is a still from Marc Karlin’s The Serpent, a film on Rupert Murdoch 28 years later.

Sources – Promise of a Dream: Remembering the Sixties. S,Rowbotham. (Verso:2002)

Picture This, Presents Marc Karlin. Nightcleaners (1975) Q&A with Mike Sperlinger and Humphry Trevelyan

The Berwick Street Collective’s Nightcleaners (1975) was filmed to support an attempt by the women’s movement to unionise London’s night cleaners. Shot in black and white, and punctuated with sections of black leader, Nightcleaners fuses political documentary with a rigorous reflection on the materiality of film and the problems of representing struggle. Here is a short scene.

The collective was founded by Marc Karlin, Humphry Treveleyan, Richard Mordaunt and James Scott. During the filming of Nightcleaners they were joined by artist Mary Kelly. Here is a bio from the early 1970s out of the archive.

Humphry Treveleyan and Marc Karlin were both members of Cinema Action, the left-wing film collective, in the late 1960s but both left dissatisfied with the group’s formal commitment to film-making. With Nightcleaners, those expecting a didactic film, found one that was nuanced and exploratory, both in terms of form and working class representation. The film used black spacing which slowly draws contemplation from the viewer and the fragmented soundtrack, together with time lapse sequences, applied pressure on the image, questioning its ability to record actuality. At the time, Screen journal declared it undoubtedly the most ‘important political film to have been made in this country’ and predicted it ‘to provide a basis for a new direction in British film-making’ . Claire Johnston’s Jump Cut review proclaimed Nightcleaners was ‘redefining the struggle for revolutionary cinema’.

The revolution failed to materialise and Nightcleaners remained firmly underground. Naturally being a collective project, Nightcleaners seeps many histories and it remains a complicated assignment to gain an exact understanding of the creative intentions of the film from those involved. To this day tensions linger, as you can witness from the exchanges between feminist writer Sheila Rowbotham, a campaigner with the Cleaners Action Group at the time, and Humphry Teveleyan in the Q&A.

That is not to say Nightcleaners ever went away. Indeed, Mike Sperlinger, LUX’s Assistant Director, states from 2002 onwards the film had regular screenings with many different audiences, striking a political chord particularly in a time where the erosion of the trade unions of the 1980s has noticeably come home to roost. Mike also observes a renewed interest in materialist film practises in oppositional film over the past ten years and Humphry Trevelyan adds the film has been adopted recently by the Occupy movement with a screening at UCL.

Nightcleaners (1974) and it’s ‘sequel’ 36′ to 77′ (1978) will soon be released by LUX on DVD.

This Q&A is chaired by Picture This director Dan Kidner with Mike Sperlinger and Humphry Treveleyan and poses the question; does a film need to explore form as well as content to be political?

Picture This presents Marc Karlin, The Serpent (1997) Q&A with Holly Aylett and Jonathan Bloom

The Serpent (1997) is a drama-documentary about Rupert Murdoch. Borrowing from Milton’s Paradise Lost, Karlin

tells the tale of commuter Michael Deakin (Nicholas Farrell), self appointed archangel, who falls asleep on his train and dreams of ridding Britain of the Dark Prince (Rupert Murdoch). The Voice of Reason stops him and not only exposes the futility of Deakin’s quest but confronts us, the silent majority, with our complicity in Murdoch’s rise to power.

Karlin guides us through the labyrinth of Murdoch’s psyche. Firstly ‘The Museum of the Fall’, a fable-like archive containing artefacts of Murdoch’s empire, where human sculptures display tabloid headlines that alter with the public mood, and where page three girls reveal the industrialisation of sex. Secondly, the telling silence that greets Murdoch’s 1989 address at the Edinburgh International Television Festival, where he calls for increased deregulation of television in the face of censorship. The Voice of Reason indicates to Deakin, “this is the silence of democrats … and the Dark Prince could bathe in that silence”

Karlin’s film is a stinging indictment on the Left’s failure to counter Murdoch’s increasing influence in the British media since the late 1960s, and consequently reveals the Left’s tendency to create their own monsters (Murdoch) in order to conceal their guilt. As Karlin remarks in an interview before his death, “In a way you could say it is a very healthy part of British democracy, whereby you invite the wolf who doesn’t disguise himself at all. But if you are going to invite the wolf, then you better start shaping up and debating.” Fifteen years later, over to you Lord Justice Leveson…

The Q&A is chaired by Picture This’ Dan Kidner, with Holly Aylett and Karlin’s cinematographer Jonathan Bloom.

The Times Between A & Z

In the recent Q&A on Marc Karlin’s Between Times (1993), the film’s editor and voice of ‘A’, Steve Sprung, declared Marc was both ‘A’ and ‘Z’. That is to say, Marc occupied the two opposing left wing positions simultaneously in the film, thereby allowing us to gain an intriguing insight into Marc’s paradoxical political outlook at the time.

Here is a fascinating transcript from the archive, that runs contrary to this claim. It is a conversation between Marc and Marxist writer, John Mepham that forms the foundations of the dialectic in Between Times. Marc and Mepham discuss the parallels between the fall of the British Left and the rise of Thatcherism since May 1968. Both seem to form the idea that all the questions and intentions at the heart of Thatcherism were made by the New Left after May 68. The New Left simply never organised their response into a coherent political project and as a consequence stagnated.

It is a very candid and engaging conversation that not only mirrors our search for fresh alternatives but also reveals our tendency to create our own political demons to disguise our complicity when things run adrift.

Picture This presents Marc Karlin, Between Times (1993)

Between Times (1993) looks at the fate of the British Left in the wake of Thatcherism. Over a cup of tea, A, the socialist, and Z, the post-modernist, investigate what now constitutes the men and women, individuals or collectives, who saw themselves as being the agency of change, i.e. until then the working class.

After the 1992 General Election defeat, the British Left were in a state of paralysis. Like today, the Left, swamped by the loudly proclaimed ‘end of history’ so often twinned with the death of Socialism, were searching for a viable alternative to the entrenched neo-liberal ideology.

In light of this, the film reveals the tension that existed between the ‘working class’ and the ‘political class’ in the early 1990s after a decade of shifting class perceptions and individual aspirations. From his notebooks at the time Karlin writes, ‘the subjects feel ill at ease in the political class’ tightly constructed corset or straight-jacket. Political language and culture does not correspond to the subject’s intimate and intuitive understanding of itself and its circumstances’.

Between Times explores the need for alternatives, new spaces and new realities that socialism, particularly the British bureaucratic variant, tended to exclude and abandon. ‘A’ notes, ‘we are taking a second breath’ and inhales fresh optimism from the Thurcroft miners attempt to buy their colliery from British Coal. To ‘Z’, however, this is just temporary turbulence. ‘Z’ used to believe these incidents added up to an organised, articulated political project, that each image was part of a continuing narrative, but now, he has come to distrust the Left’s history and its propensity to cling to, what he now believes to be, disparate imagery.

In a letter to his cinematographer Jonathan Bloom, Karlin states,

Between Times Fax © The Marc Karlin Archive

The Q&A includes Kodwo Eshun, artist, theorist and co-founder of the Otolith Group, Steve Sprung, filmmaker and editor of Between Times, and Picture This’ director Dan Kidner.

Picture This Presents Marc Karlin, For Memory (1982) Q&A.

For Memory (originally TV and Memory) was a co-production between the BFI and the BBC. Marc Karlin started writing it in 1975, shot it between 1977 and 1978 and concluded editing in 1982. Ironically, a film about TV and Memory was forgotten. It remained neglected until the BBC finally broadcast the film in a sleepy afternoon slot in March 1986.

For Memory is a contemplation on cultural amnesia. Karlin, with his cinematographer Jonathan Bloom, built a model city in a studio. The camera snakes around the imagery city, seeking out fragile testimonies from voices that fail to conform to a collective history. It is an essay on a city that forgets and remembers, and how it forgets and how it remembers. Historians E.P Thompson and Cliff Williams, anti-fascist activist Charlie Goodman and Alzheimer sufferers deliver banished memories from outside the city’s bounds.

The film opens with an emotional interview with the members of the British Army Film Unit recalling the images they recorded after the liberation of the Belsen Concentration Camp. Karlin wrote For Memory as a reaction to Holocaust, Hollywood’s serialisation of the genocide. He asks: how could a documentary photograph die so soon and be taken over by a fiction?

The Q&A is chaired by Holly Aylett, documentary filmmaker, lecturer and cultural sector director, Luke Fowler, a Glasgow based artist and filmmaker, and Sheila Rowbotham, Writer in Residence at the Eccles Centre for American studies in the British Library.

The Serpent, The Cancer and Rupert.

The Serpent (1997) was originally entitled The Cancer in tribute to Dennis Potter, who named his pancreatic tumour “Rupert” in his famous interview with Melvyn Bragg. Potter, in a parting shot, stated he would love to shoot Rupert Murdoch, who not only lowered the standards of British journalism but had contributed to the wholesale pollution of British political discourse. The Serpent, Marc Karlin’s film broadcast on Channel 4 in 1997, is a fantasy drama-documentary told through Milton’s Paradise Lost. Rupert Murdoch is cast as the dark prince and Michael Deakin, played by Nicholas Farrell, a liberal, London based architect, sets out to destroy the mogul who has made England, “a hard, sniggering, resentful, hard shoulder of a place”.

What stops Deakin in this quest is his Voice of Reason, “Could it really be the devil that has given you 5,000 channels – soaps, sport, sci-fi, music, games, arts, education, videos on demand, data services? Free will on this earth has been restored and, according to you it is the devil that has done it”. Karlin’s film is an indictment on the liberal establishment’s failure to do anything about Murdoch’s increasing influence in British media. He reveals how readily the Left of the 1980s and 90s have created their own demons in order to conceal their own stagnation.

Karlin integrates footage of Murdoch’s 1989 address at the Edinburgh International Television Festival to illustrate the sheer lack of any oppostion. The camera zooms in on the audience of British TV executives, who listen in respectful silence as this self-styled champion of liberty mounts a pulpit to accuse them of waging the same sort of thought control as the established church before the invention of the printing press. The Voice of Reason indicates to Deakin, “this is the silence of democrats … and the Dark Prince could bathe in that silence”

Here is an excerpt from a Radio 4 interview broadcast in February 1999. Marc is being interviewed by Patrick Wright on his Outriders programme.

PW: You’ve also got in that film footage of Murdoch himself talking at Edinburgh. There he is, and he’s outlining his vision, saying this is the new – almost the Copernican revolution! We’re going to turn the world of media upside down, we’re going to deregulate, there are going to be a thousand channels of whatever. You then show the audience, who are basically television professionals to a man, and a woman too, I guess, looking apprehensive and saying nothing. And, you’ve talked about silence. Now, in a lot of your recent films you re-show television footage, whether it be Newsnight or whatever, whether it be people responding to how marvellous Princess Diana was… And you show your own impatience by revealing images of inertia, of concessions you think should never be made. What is that we should have done with Murdoch?

MK: Well, I find it pretty strange they invited him. In a way you could say it is a very healthy part of British democracy, whereby you invite the wolf who doesn’t disguise himself at all. But if you are going to invite the wolf, then you better start shaping up and debating. I mean, I think Murdoch in The Serpent… I think he does represent the real contradictions of Milton’s Satan, so the Edinburgh Festival thing was about that contradiction. On the one hand you invite him, on the other you don’t fight against him. You say: “How terrible it is, Murdoch is going to ruin England!” You know, the number of articles that have been written about Murdoch ruining England, as if those people who have been ruined have had no participation in it whatsoever. They are virgins, they are white paper, they have no soul, they have no passion, they have no heart, they have no ideas, nothing. Murdoch, apparently, has walked all over them. It’s Murdoch who’s done it, not us. That really does make me angry, because you can’t have your cake and eat it. I mean, you can’t, on the one hand say: “We’re democrats, therefore Murdoch can do everything he wants” and on the other: “We can’t stand for our own values because that would be imposing.” That would be saying: “This is what we stand for,” and that would be hideous because that means we would be censorious!

The Serpent is a pertinent reminder of our own culpability surrounding Murdoch’s rise to power, like a cancer being very much part of us and not a foreign body however strongly we deny its existence. The film succeeds in offering a passionate and multifaceted argument to the present debate, overshadowed by the relationship between the press and politicians, and one that perhaps is being neglected by the Leveson Inquiry.

The film was recently screen at the Arnolfini at the Mark Karlin weekend with Picture This. A Q&A with Jonathan Bloom, The Serpent’s cinemathagrapher, Holly Aylett, former editor of Vertigo Magazine, and Picture This‘ Dan Kidner will go up shortly.

Sources

Picture This presents Marc Karlin, Roundtable discussion.

This month Picture This, in association with the research project “In the Spirit of Marc Karlin”, held an exhibition and screening programme focusing on the work of British filmmaker Marc Karlin (1943-99). Marc Karlin is an important but neglected figure within the British film avant-garde of the 1970s, 80s and 90s.

Arnolfini, hosted a weekend of screenings and talks which began with the seminal, Nightcleaners (1974). Shot in black and white, and punctuated with sections of black leader, Nightcleaners fuses political documentary with a rigorous reflection on the materiality of film and the problems of representing struggle. The programme continued with three films that Karlin made for television in the 1980s and 90s. For Memory (1986), features E.P. Thompson, and explores historical memory, Between Times (1993) looks at the fate of the British Left in the wake of Thatcherism, and The Serpent (1997) is a drama-documentary about Rupert Murdoch told through the lens of Milton’s Paradise Lost. Each film brilliantly captures the mood of the left in Britain through the 80s and 90s, whilst the aesthetic and political issues, and questions, they raise remain relevant and urgent.

The weekend ended with a round table discussion with contributors Holly Aylett, Jonathan Bloom, Kodwo Eshun, Luke Fowler, Andy Robson, Sheila Rowbotham, Steve Sprung and hosted by Dan Kidner.Picture This presents Marc Karlin, Roundtable discussion.

The audio from the weekend’s Q&As will soon be up.